Introduction and Course Overview

The Interstellar medium course is at once a course about nothing and a course about everything. What I mean by that is we’re talking about the space between things, some of the least dense parts of the galaxy. But we’re also going to touch on nearly all aspects of astrophysics:

- quantum mechanics of atoms and molecules

- radiative transfer

- star formation

- planet formation

- galactic stellar populations

- and even cosmology (slightly)

That’s because this course is fundamentally about the interactions between all of these more easily-defined “units” of astrophysics. The science lectures in this course will basically fall into one or two categories:

- coverage/review of fundamental concepts/theories (e.g., quantum mechanics, radiative transfer, etc…)

- applying/integrating those concepts to understanding the interstellar medium (e.g., dust emission, star formation, etc…)

We’ll be talking about many fundamental astrophysical concepts in some detail (warning: not as much detail as courses designed to cover these subjects, but enough detail so that you’ll be able to follow along if you haven’t taken these courses already, or if you forgot)!

What is a graduate course?

Compared to undergraduate courses, graduate courses are one step closer to operating at the interface between established knowledge and full-blown research. Graduate courses try to distill (sometimes very recently gained) knowledge into an efficient format for learning. Or, at least, a more efficient format than the alternative, which would be trying to assemble the knowledge oneself through reading various scientific articles. At the end of your Ph.D., you’ll look back on the series of papers you’ve written and the talks you’ve given at various conferences, and you’ll have your own set of new discoveries and topics that you know in better detail than nearly everyone else on this planet. Now, the question is, how can you efficiently teach a new generation the core concepts? That’s essentially what a graduate course is trying to do.

Course Schedule

- First third: coverage/review of quantum mechanics, collisional processes, statistical mechanics, radiative transfer, absorption and emission lines, radiation fields, etc…, with a focus on the processes necessary for understanding the components of the interstellar medium. References: Draine textbook Chs 2 - 14

- Second third: star formation, generally: clouds, astrochemistry, shocks, CO surveys, protostars. References: Draine textbook Chs 14 - 42 (not all covered)

- Final third: protoplanetary disks, planet formation, exoplanets, radio astronomy, ALMA proposals. References: additional resources.

Course Syllabus

Format

- 3 midterm exams (total 40%)

- three problem sets (total 20%)

- paper presentation (choose two dates Monday, August 30th) (15%)

- reviews from mock TAC (5%)

- ALMA proposal (20%)

- no final

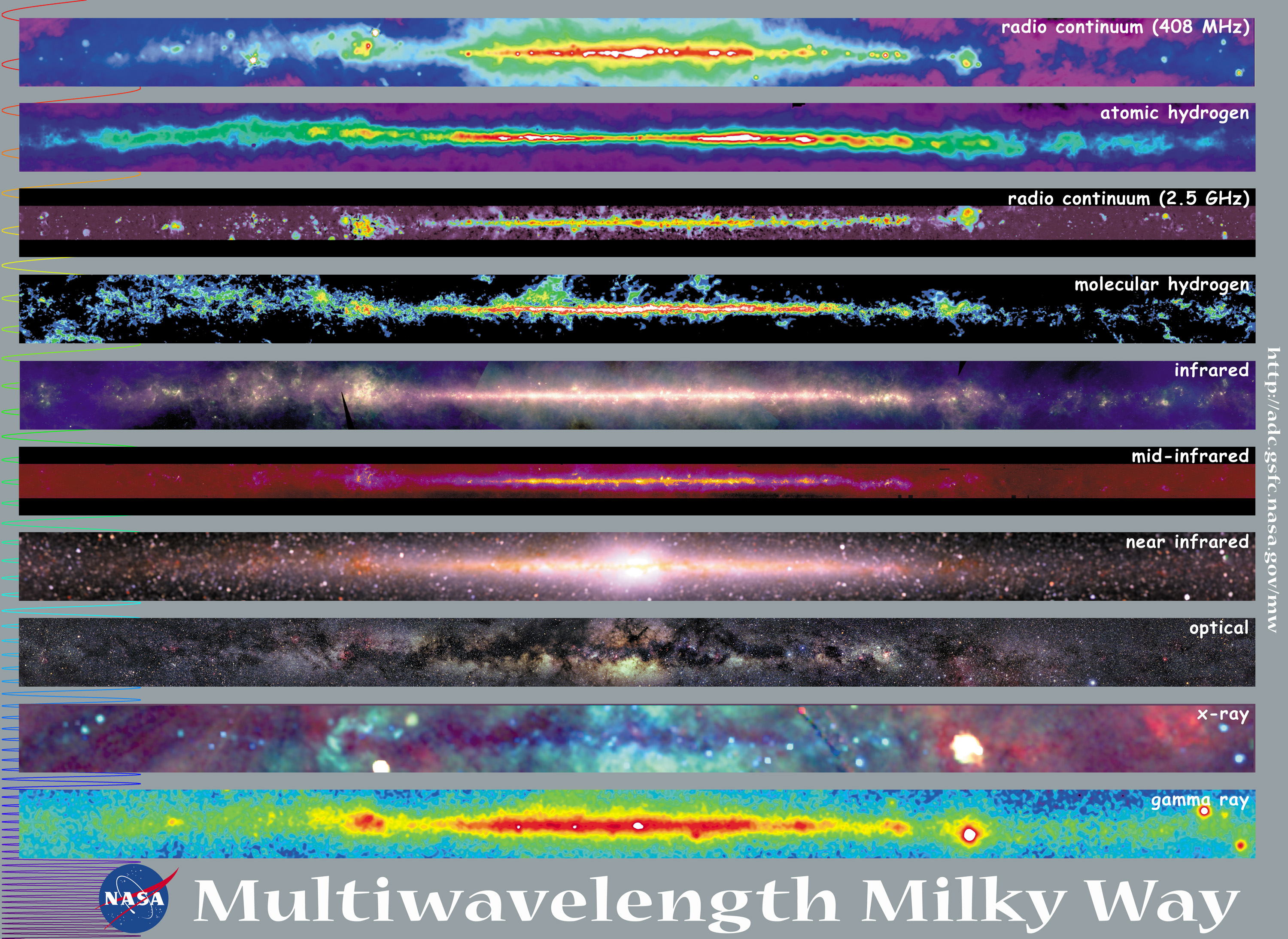

What is the ISM?

- primarily, the disks of galaxies

- Gigantic range of \(T\) (\(10 - 10^6\)) and number density \(n\) (\(10^{-3} - 10^{-6} \mathrm{cm}^{-3}\))

- wide range of ionization states

- spatially inhomogeneous

- roughly solar abundances

- multi-phase

- far from equilibrium/steady-state

A multi-wavelength view of the Milky Way. Image Credit: NASA

ISM nomenclature

Throughout this course we will be frequently discussing neutral atomic hydrogen, ionized atomic hydrogen (i.e., protons), and (neutral )molecular hydrogen. Atomic spectroscopists denote ionization states with Roman numerals, with I corresponding to the neutral case.

Take Calcium, for example. Neutral Calcium is Ca I, singly ionized Calcium is Ca II, and five-times ionized Calcium is Ca IV.

- Neutral Hydrogen: H I

- Singly-ionized Hydrogen (i.e., a proton): H II

- Molecular Hydrogen: \(H_2\)

When we say “H two,” which do we mean? In this course, at least, we’ll strive to maintain the convention that H II == “H two,” and when we are referring to \(H_2\), we will say “molecular hydrogen.”

ISM is mostly hydrogen. Hydrogen states by mass (following Draine Table 1.2).

Phases of the ISM

Why does it matter that we have a clear distinction between the forms of Hydrogen? Because Hydrogen is the most abundant element (cosmologically speaking), and these trace the phases of the ISM.

What do we mean by phases of the ISM? Broadly speaking, these are characteristic states of the baryons in the ISM. Different authors will make different levels of distinction, i.e., “two-phase” or “three-phase” ISM. In the case of Draine (Table 1.3), we have seven phases. In the case of Ryden and Pogge, we have five phases. Recognize that ultimately the “phases” are a continuum of states, and that it makes sense to group things into phases based upon the physical processes that occur with them.

Don’t worry too much about the exact boundaries of each phase, but instead focus on the huge, orders of magnitude range in densities, temperatures, and volume fractions. If you wanted to chose a most-important phase based on volume, you’re going to get a different answer than if you chose one based on mass.

For now, let’s just reflect on Draine Table 1.3 / Ryden and Pogge Table 1.1.

We see combinations of temperature, density, and ionization state. The point of this course is basically understanding the interaction between these phases. Following Draine,

- Coronal gas, “hot ionized medium” or “HIM”

- H II gas, dense H II regions, diffuse H II regions, “warm ionized medium” or “WIM”

- Warm H I, “warm neutral medium” or “WNM”

- Cool H I, “cold neutral medium” or “CNM”

- Diffuse molecular gas

- Dense molecular gas

- Stellar outflows

Ryden and Pogge lump all molecular gas together, and don’t differentiate stellar outflows.

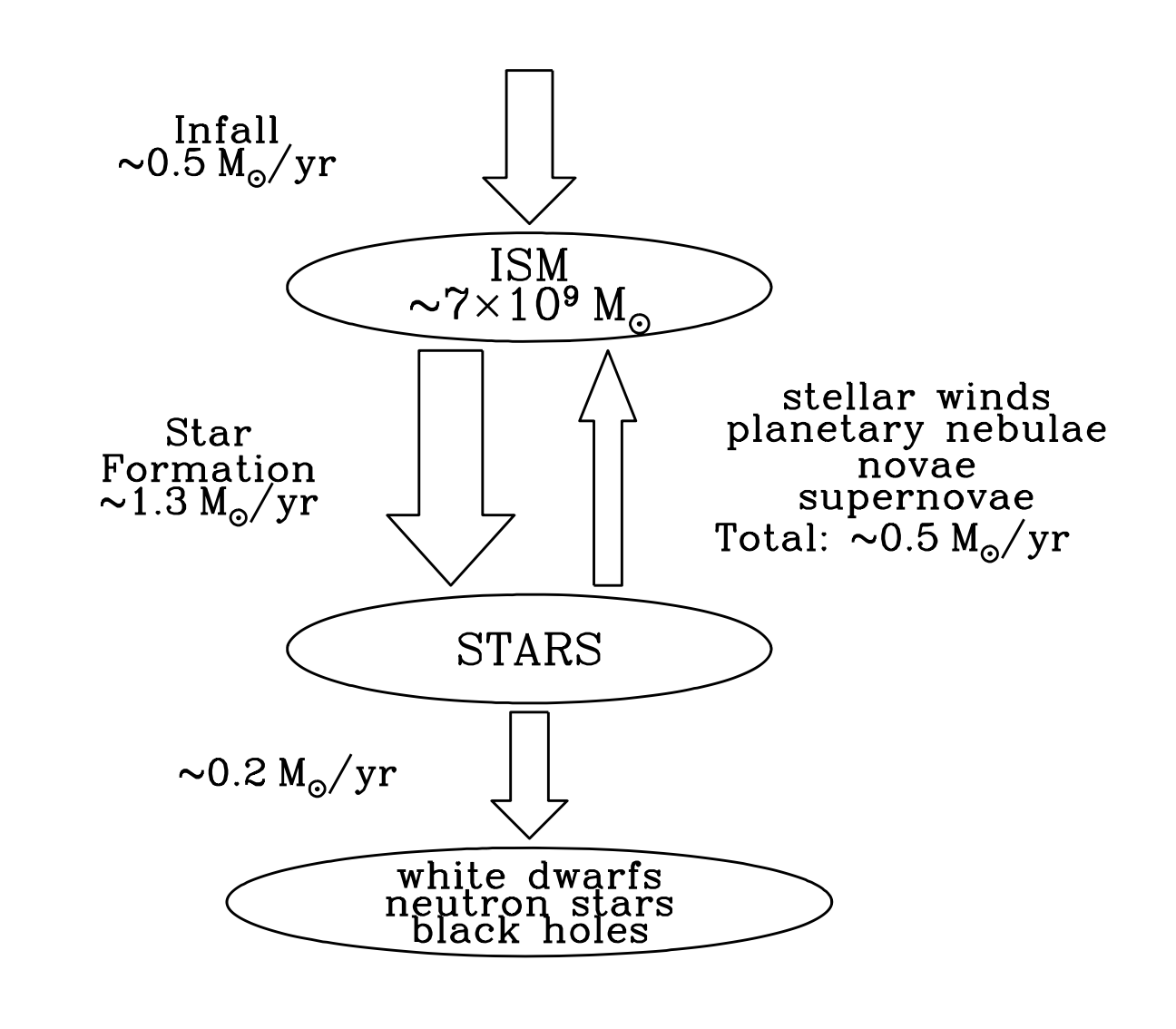

The ISM is dynamic, and baryons in each of these phases can change into others. Ionizing photons will turn cold molecular gas to hot ionized hydrogen (HII); hot gas can cool to lower temperatures through radiative cooling; ions and electrons can recombine into atoms, and atoms can recombine to form \(H_2\) molecules.

Let’s explore these phases through graphs.

Sources of Energy in ISM

- Photons: CMB photons, infrared photons emitted from dust, and starlight

- Cosmic rays

- Magnetic field energy

- Bulk kinetic energy

All energy densities are approximately similar, and makes sense from a coupling standpoint.

Flow of energy in the Milky Way (Draine Figure 1.3)

Historical beginnings of ISM observations

Ryden and Pogge Ch 1.1

Nebulae

- Orion nebulae (1610), gas clouds

- Messier catalog (1787) contains many nebulae

- Kant and Laplace (1755/1797) nebular hypothesis

- William Huggins (1860s) spectra of planetary nebula, diffuse gas

- Henry Draper (1880) photographs orion nebula

The Orion Nebula. Image Credit: Alejandro Lopez

Interstellar absorption lines

- Hartmann (1904): stationary narrow line in a broad oscillating Ca II stellar line in a binary \(\delta\)-Ori (O9.5 star).

- Up until space astronomy, high spectral resolutions of absorption lines in stars was the main way to study cool interstellar clouds

- UV satellites like Copernicus, then IUE, HST, and FUSE allowed main transitions of HI, Lyman alpha, H2, etc. to be studied.

Dark clouds

Modern image:

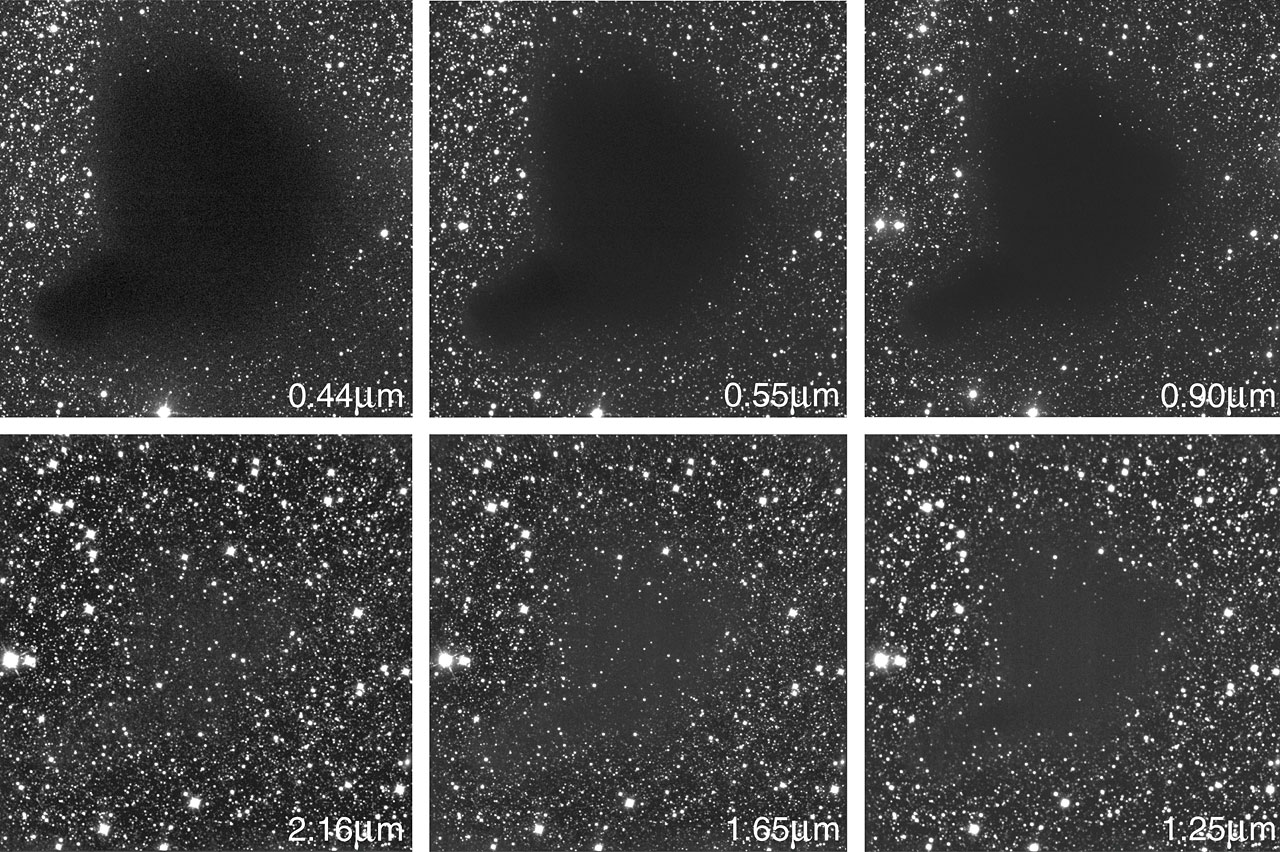

The dark cloud B68 at different wavelegths. Credit: ESO

What’s going on here?

- extinction diminishes with wavelength

- centers of clouds are denser than peripheries

We see these in the visible light image of the Milky Way.