Statistical Mechanics and Thermodynamic Equilibrium

Draine Ch. 3

Also good review is “An Introduction to Thermal Physics” by Daniel V. Schroeder, esp. Ch 6 “Boltzmann Statistics.”

The ISM and IGM are generally far from thermodynamic equilibrium.

But, to understand the nonequilibrium conditions, we first need to understand the equilibrium conditions, which are useful for relating forward and reverse reaction rates of ionization and recombination processes important to the ISM.

Local thermodynamic equilibrium: emission properties can be calculated from measured properties and temperature. Key point is that we can define temperature and it has some bearing on the microphysics of the fluid.

For example, LTE exists in a glass of water containing a melting ice cube. Temperature can be defined at any point, and if the energies of the molecules at a specific point are measured, they will follow a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution with that temperature (Wikipedia).

LTE also exists in the photospheres of stars.

Partition functions

The partition function \(Z\) is a dimensionless number describing a physical system, e.g., some set of particles in a box with volume \(V\). It allows you to understand the macrostates of the system from the microstates of the system.

If you know the partition function, you can calculate energy, pressure, magnetization, entropy, etc.

For a classical discrete system, the partition function is $$ Z(T) = \sum_s e^{- E(s)/kT} $$ sum is over all possible states \(s\) of the system, and \(E(s)\) is the energy of state \(s\).

For a continuous system, the partition function is expressed using an integral (since the set of microstates as a function of position and momentum is infinite)

$$ Z(X, T) = \frac{V}{h^3} \int_0^\infty 4 \pi p^2 \, \mathrm{d}p \; e^{-p^2/2 M_x k T} $$ where \(M_X\) is the mass of the particle.

For dilute gases, we generally need to talk about both types of partition functions, since the gas particles can have both translational motion and internal energy (i.e., quantum states)

$$ Z(T) = Z_\mathrm{tran}(T) z_\mathrm{int}(T) $$

the translational partition function is

$$ Z_\mathrm{tran} = \frac{(2 \pi M_X k T)^{3/2}}{h^3} V $$

The internal partition function is a sum over the possible internal states of \(X\) $$ z_\mathrm{int}(X; T) = \sum_i g_i e^{E_i/kT} $$ where \(g_i\) is the degeneracy of level \(i\), or the number of quantum states grouped together in the same energy level.

For example, a free electron has just two internal states (spin up and down), both of which have \(E_i = 0\), so \(z_\mathrm{int} = 2\).

Finally, we will define the partition function per unit volume $$ f(X; T) = \frac{Z}{V} = \left [ \frac{(2 \pi M_X k T)^{3/2}}{h^3} \right] z_\mathrm{int}(X; T) $$

Detailed balance: law of mass action

Suppose there is a chemical reaction \(A + B \leftrightarrow C\), which is in local thermodynamic equilibrium. Statistical mechanics tells us that the LTE abundance of species \(X\) is proportional to \(f(X)\).

And therefore the number densities of the species satisfy the law of mass action

$$ \frac{n_C}{n_A n_B} = \frac{f(C)}{f(A) f(B)}. $$

Basically, in LTE, the ratio of the product of number densities is equal to the ratio of the product of partition functions $$ \frac{\prod_i n_{\mathrm{left},i}}{\prod_i n_{\mathrm{right},i}} = \frac{\prod_i f_{\mathrm{left},i}}{\prod_i f_{\mathrm{right},i}} $$

more details in Draine 3.2.

As we mentioned, the partition function is useful for describing the macrostates of the system. If we want to find the ratio of number densities of a species, then we can just use the ratio of the partition functions.

Ionization and Recombination

Let’s apply this understanding to the case of recombination and ionization, where an electron recombines with an ionized atom, moving its energy level in the process $$ e^- + X_u^{+r +1} \leftrightarrow X_l^{+r} $$ Say we know the abundance of \(X_u^{+r+1}\) and \(n_e\), that the system is in LTE, and the energies of the two states (\(E_{r,l}\) and \(E_{r+1, u}\)). What is the abundance of \(X_l^{+r}\)?

Let’s remember our left-hand-side / right-hand-side balance

$$ \frac{n(X_l^{+r})}{n(X_u^{+r+1})n(e^-)} = \frac{z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{X_l^{+r}}}}{z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{X_u^{+r+1}}}z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{e^-}}}. $$

We just calculated \(z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{e^-}}\), and its 2. So we have

$$ n(X_l^{+r}) = n(X_u^{+r+1})n(e^-) \frac{1}{2} \left ( \frac{z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{X_l^{+r}}}}{z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{X_u^{+r+1}}}} \right ) $$

looking back to the partition function definition, the bracketed term is (relatively) easy to calculate, because we only have a single energy level under consideration for each species (no sum)

$$ \frac{z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{X_l^{+r}}}}{z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{X_u^{+r+1}}}} = \frac{g(X_l^{+r}) e^{-E_{r,l}/kT}}{g(X_u^{+r+1}) e^{-E_{r+1,u}/kT}} $$

and there, we’ve solved for \(n(X_l^{+r})\).

Saha Equation

Bengali physicist Meghnad Saha in 1920. Combining ideas of quantum mechanics and statistical mechanics to explain spectral classification of stars. Is the reason why we see drastically different spectral absorption lines in stars as a function of temperature, even though all stars are majority hydrogen composition.

Lets expand the previous example by considering all energy levels of \(X^{+r}\) and \(X^{+r+1}\).

$$ e^- + X^{+r +1} \leftrightarrow X^{+r} $$

same thing with the left-hand-side / right-hand-side balance, only though now we need to consider all levels

$$ \frac{n(X^{+r})}{n(X^{+r+1})n(e^-)} = \frac{z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{X^{+r}}}}{z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{X^{+r+1}}}z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{e^-}}}. $$

which means we need to consider all levels in the partition function calculation.

$$ \frac{z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{X^{+r}}}}{z_{\mathrm{int},\mathrm{X^{+r+1}}}} = \frac{\sum_j g_{r,j} e^{-E_{r,j}/kT}}{\sum_j g_{r+1,j} e^{-E_{r+1,j}/kT}} $$

If the temperature is sufficiently low that only the lowest energy level states are significant in the calculation of the partition function (\(e^{-E_i/kT}\)). If \(T\) is large, then \(e^{-E_i/kT} \rightarrow 0\) as \(E_i\) increases.

Let the ionization energy be given by $$ \Phi_r = E_{r+1,1} - E_{r,1} $$ then the Saha equation is $$ \frac{n(e^-) n(X^{+r+1})}{n(X^{+r})} \approx \frac{2(2 \pi m_e kT)^{3/2}}{h^3} \frac{g_{r+1,1}}{g_{r,1}}e^{-\Phi_r/kT} $$

again, all of this is assuming local thermodynamic equilibrium. Good for stellar interiors, but not a good approximation in the ISM or IGM.

Ratios of rate coefficients

Assuming we are in local thermodynamic equilibrium and that the reaction is in equilibrium, how can we use the law of mass action to calculate the ratio of rate coefficients?

Consider the inelastic scattering reaction $$ X(l) + Y \rightarrow X(u) + Y $$

Since we are in LTE, you can think of there being a “bath” of species \(Y\) that, given the opportunity, will react with both \(X(l)\) and \(X(u)\). Assume \(Y\) is a collisional partner that does not change internal state during the interaction.

What do we know from law of mass action?

$$ \frac{n(X(u)) n(Y)}{n(X(l))n(Y)} = \frac{f(X(u))f(Y)}{f(X(l))f(Y)} = \frac{z_\mathrm{int}(X(u))}{z_\mathrm{int}(X(l))} $$

What do we know from conservation of mass? $$ n(X(u)) n(Y) \langle \sigma v \rangle_{l \rightarrow u} = n(X(u)) n(Y) \langle \sigma v \rangle_{u \rightarrow l}. $$

Rearrange these to find $$ \frac{\langle \sigma v \rangle_{l \rightarrow u}}{\langle \sigma v \rangle_{u \rightarrow l}} = \frac{z_\mathrm{int}(X(u))}{z_\mathrm{int}(X(l))} = \frac{g_u}{g_l} e^{-(E_u - E_l)/kT} $$

More info in Draine 3.5.

These relationships can also be used to put conditions on the ratios of cross sections. See Draine 3.6 for more details.

Three body recombination

Can be important for hydrogen recombination, especially higher energy levels.

$$ H^+ + e^- + e^- \rightarrow H(n) + e^- $$

Draine 3.7 has some calculations for this, the interesting result being that the number density \(n(H(n)) \propto n^2\). You can think of this as one electron loosing just enough energy to become bound at a higher energy level.

Departure coefficients

Draine 3.8

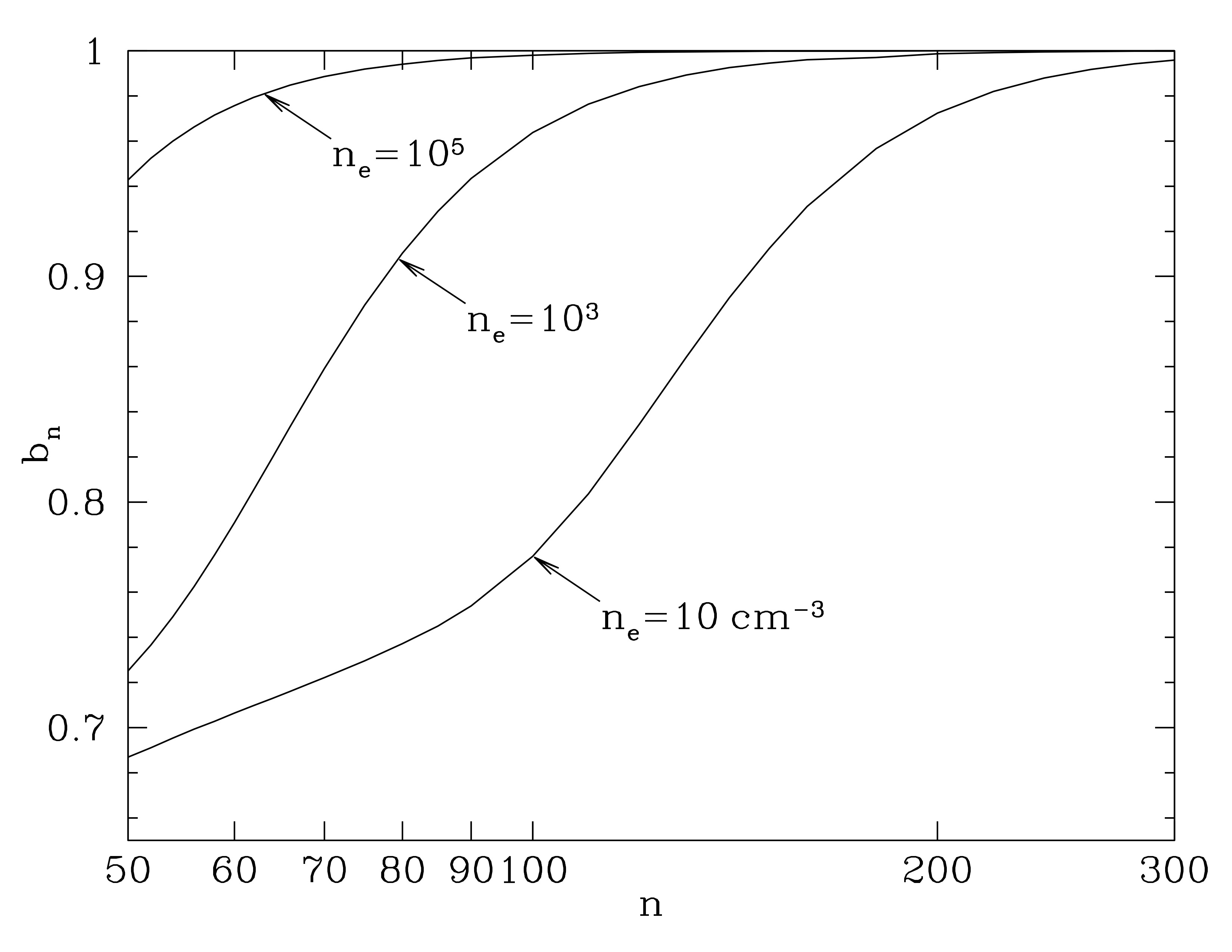

The departure coefficient is the ratio of the actual number density to the number density if one were in LTE

$$ b_n \equiv \frac{n[H(n)]}{n_\mathrm{LTE}[H(n)]} $$

If we were only considering collisional processes like collisional ionization and three-body recombination, then \(b_n = 1\). Important to recognize that collisions do the thermalization that brings a parcel of gas into LTE. This is why most higher density things can be assumed to be in LTE (Sun’s photosphere, earth’s atmosphere, regions of protoplanetary disks, etc…) but we can get in trouble when we go to less dense regions.

In less dense regions, the excited states can be depopulated by spontaneous emission at rates comparable or exceeding collisional dexcitation (or recombination). The spontaneous emission rate is larger for smaller \(n\), yielding the following plot for hydrogen atoms

Departure coefficient \(b_n\) as a function of principle quantum number \(n\), for hydrogen atoms in thermal plasma with \(T=10^{3.9}\) K, for three different densities. The departure coefficient gets quite large for diffuse regions. Attribution: Draine Figure 3.1

High \(n\) levels are interesting things. Transitions from $$ n + 1 \rightarrow 1 $$ principal states are called \(n\alpha\) transitions. E.g., Lyman \(\alpha\) is the \(1\alpha\) transition.

When \(n\) becomes very large, the photon is in the radio band of the spectrum, and these are called “radio recombination lines.” E.g., we might talk about the \(166\alpha\) or \(159\alpha\) transitions.

The curve of \(b_n(n)\) also sets up conditions so that maser amplification can occur.