Energy Levels of Atoms, Ions, and Molecules

- Draine Ch. 4 + 5

- Ryden and Pogge “Guide to Spectroscopic Notation” available as PDF from here.

- Radiative Processes by Rybicki and Lightman, Ch. 11: Molecular Structure

- Physics of Atoms and Molecules by Bransden and Joachain

Some of this lecture will likely be review from your quantum mechanics (and/or chemistry) courses. The goal is to revisit and organize our understanding of the energy levels of atoms, ions, and molecules to form a foundation for later astrophysical processes that use these emission/absorption lines.

Ionization

As we covered in the first lecture (with hydrogen), ionization state is denoted by a Roman numeral (especially for spectroscopic purposes)

- O I = neutral oxygen

- O II = singly ionized oxygen

- Ne III = doubly ionized neon

Sometimes, you may see the more conventional “chemical” notation when we’re just referring to the ion, i.e., \(\mathrm{Ne}^{4+}\).

Single-Electron orbitals

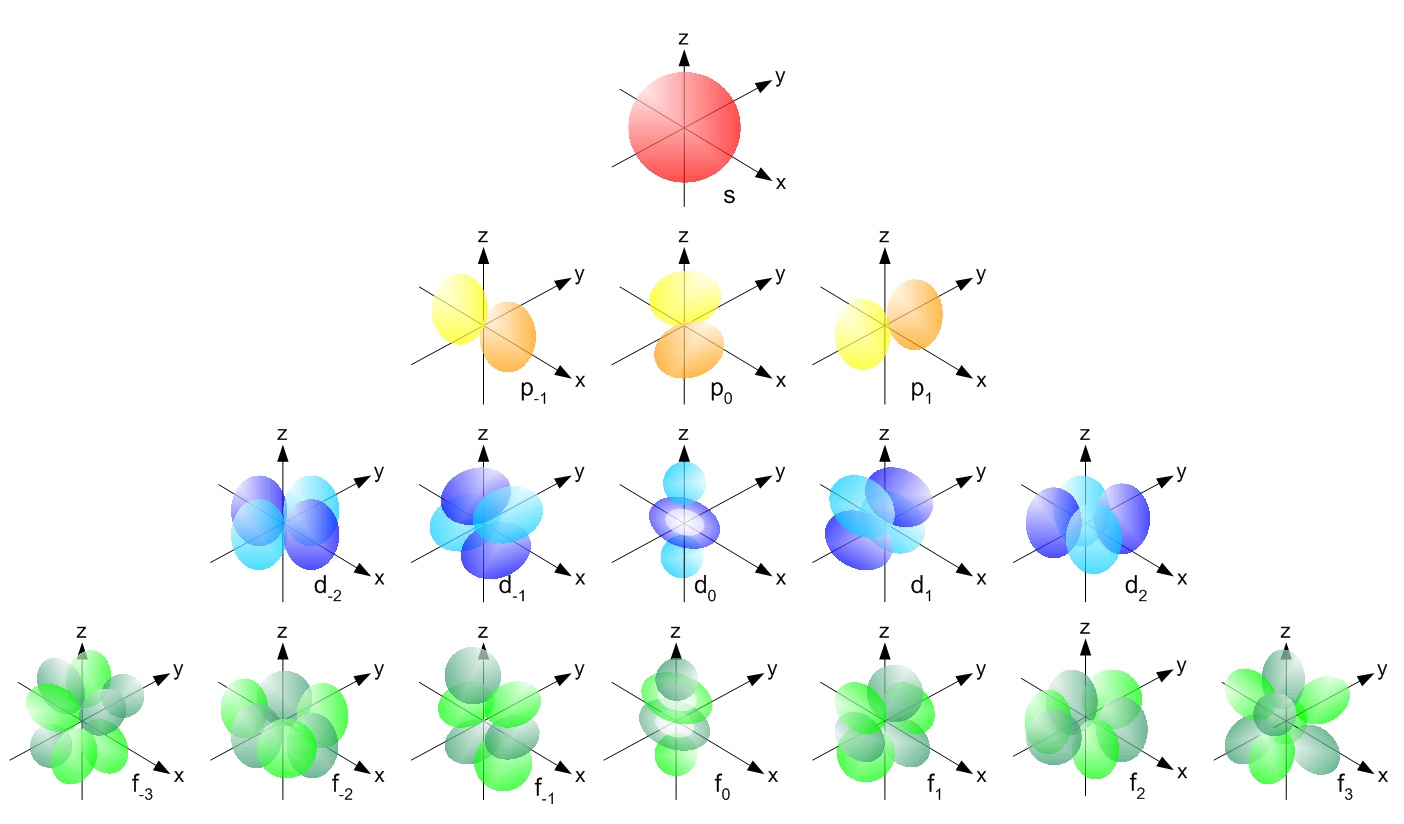

- \(n\) principal quantum number (electron energy or “shell” level). You may see these labeled using K, L, M for \(n=1,2,3\)…, especially if you do x-ray science.

- \(l\) orbital angular momentum in units of \(\hbar\) (orbital type, s, p, d, f corresponding to \(l=0,1,2,3\)). Letters themselves are a holdover from pre-quantum empirical lab studies.

For given \(n\), \(l\) can take on values \(0 \leq l < n\).

- \(m_l\) (Drain calls it \(m_z\)) is the projection of orbital angular momentum onto the \(z\) axis and called the “magnetic” quantum number. If no applied magnetic field, energy for two \(m_l\) values are the same. Can take on \(2l + 1\) different values: \(m_l = -l, \ldots, -1, 0, 1, \dots l\).

- \(m_s\) is the projection of spin onto the \(z\) axis. Electrons are spin \(1/2\) particles, so projection only takes on two values. Degenerate energies if no applied field.

So a given pair of quantum numbers \(nl\) refers to \(2(2l + 1)\) distinct wavefunctions.

Pauli exclusion principal

Two electrons cannot share the same wavefunction.

- each \(nl\) subshell can have at most \(2(2l + 1)\) electrons

- \(s = 2\)

- \(p = 6\)

- \(d = 10\)

- \(f = 14\)

Visualization of the electron orbitals. From Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps, Libretexts

Orbitals are filled in order of: 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, 5s, 4d, 5p, 6s, 4f, 5d, 6p, 7s, 5f, 6d, 7p.

And we can denote the state of electrons in an atom using superscripts, e.g., for \(\mathrm{Mg}\,\mathrm{I}\) $$ 1\mathrm{s}^2\,2\mathrm{s}^2\,2\mathrm{p}^6\,3\mathrm{s}^2 $$

Spectroscopic terms

The spectral lines we observe are most commonly the result of the interactions among the electrons in the outermost shell, called the “optically active” electrons.

There are three relevant vectors and corresponding quantum numbers

- \(\boldsymbol{L}\) is total orbital angular momentum of electrons in outermost shell, with corresponding quantum number \(m_L = \sum m_l\), the projection of the total orbital angular momentum \(L \hbar\) onto the \(z\)-axis.

- \(\boldsymbol{S}\) is the total spin angular momentum of the electrons in the shell, and has an associated quantum number \(m_S = \sum m_s\), the projection of the total spin angular momentum \( S \hbar\) onto the z-axis.

- \(\boldsymbol{J} = \boldsymbol{L} + \boldsymbol{S}\) is the total (orbital + spin) angular momentum of the electrons. This term arises because of the coupling between the orbital and spin angular momentum, called the L-S coupling.

Permitted, semi-forbidden, and forbidden radiative transitions

Dipole selection rules determine whether a transition is “permitted” or not.

“Semi-forbidden” and “forbidden” radiative transitions are not strictly forbidden. It’s just that their transition probabilities (Einstein A coefficients) are much smaller than permitted lines (with forbidden lines being less likely still).

- Semi-forbidden \(\mathrm{O\,III}],\lambda1666 \)Å

- Forbidden \([\mathrm{O\,III}],\lambda5007 \)Å

In terrestrial settings, it’s more likely that an atom will be collisionally de-excited than emit in said transition. So it’s more accurate to call these “terrestrially-forbidden” transitions.

Hyperfine Structure

If the nucleus has a non-zero magnetic moment, the interaction of the magnetic fields of the nucleus and electrons gives rise to a small energy difference, which is called hyperfine structure. The hyperfine quantum number is $$ \boldsymbol{F} = \boldsymbol{I} + \boldsymbol{J} $$ where \(\boldsymbol{I}\) is the quantized spin angular momentum.

The most famous of these is the 21.106 cm line of neutral hydrogen (H I), i.e., the “21-cm” line, corresponding to the electron “spin-flip.”

But see also the hyperfine lines of HCN and \(\mathrm{C}_2 \mathrm{H}\) in protoplanetary disks.

Molecular Spectroscopy

Molecular spectroscopy is hard. But worthwhile. Why is molecular spectroscopy hard? Having two (or more) atoms destroys the nice symmetry that we had with atomic spectra. This means that there are many more ways for a molecule to move, which means many more degrees of freedom, which means many more quantum states to transition between and thus many more discrete photon energies to emit.

Most abundant, astrophysically-interesting molecules are diatomic molecules (having two atoms). Thankfully, this means we at least have a line of rotational symmetry along the internuclear axis, the line from one nucleus to another.

- homonuclear: having the same nucleus (e.g., \(H_2\), \(O_2\))

- heteronuclear: having different nuclei (e.g., \(HD\), \(CO\) )

The main types of molecular transitions that you will encounter in astrophysical contexts are either vibrational or rotational.

Vibrational Transitions

Due to the quantization of the vibrational energy as atoms stretch on the internuclear axis.

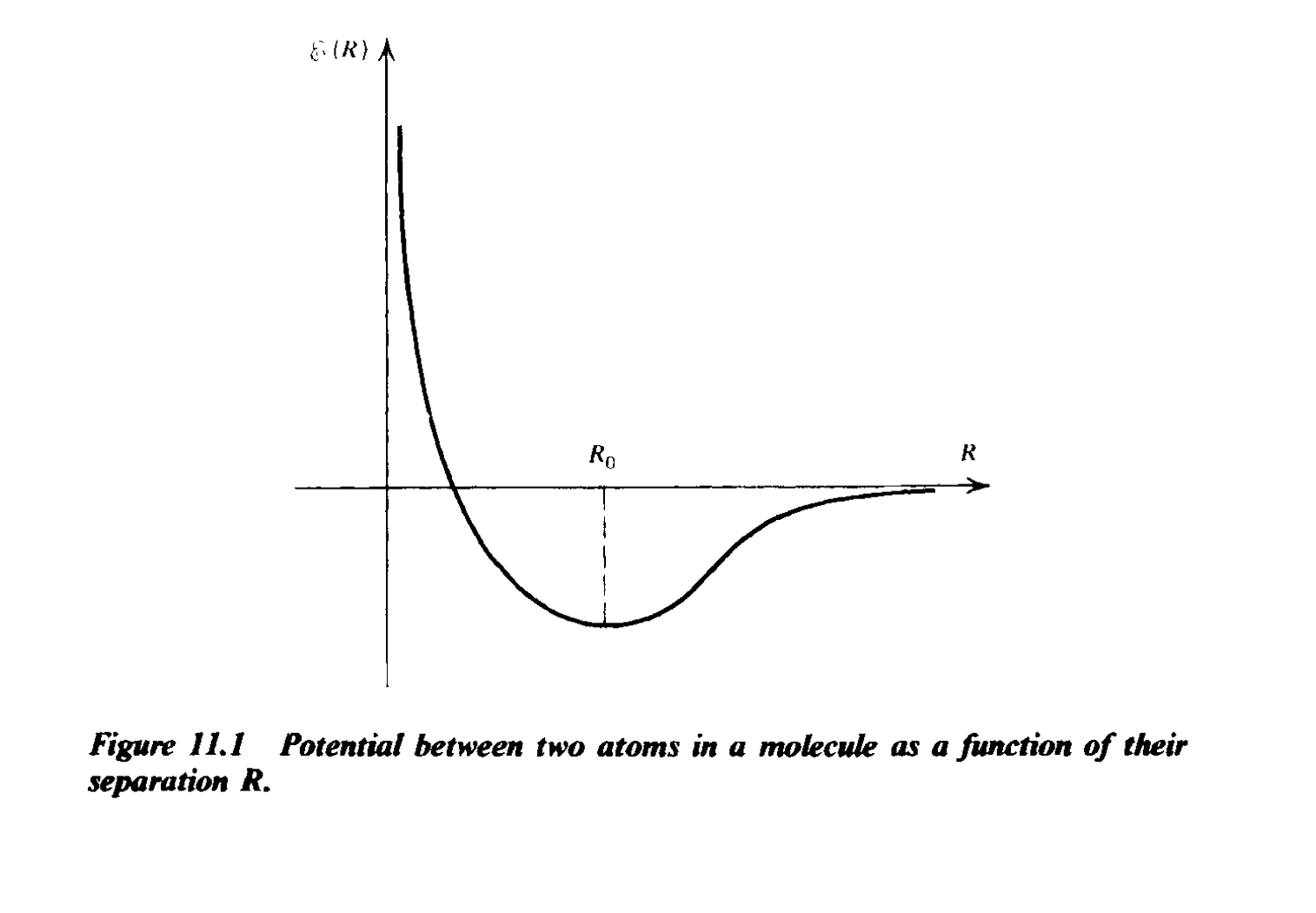

The potential between two atoms in a molecule as a function of their separation. Attribution: Figure 11.1 from ‘Radiative Processes’ by Rybicki and Lightman

Ground state is very near the bottom (but not completely so).

Can be approximated as a harmonic oscillator with quantum number \(v\), and vibrational energy levels $$ E_\mathrm{vib}(v) = \hbar \omega_0 (v + 1/2). $$ where $$ \omega_0 = \sqrt{k/m_r} $$ where in this case only, \(k\) is the spring constant for the harmonic oscillator. \(m_r\) is the reduced mass $$ m_r = \frac{m_1 m_2}{m_1 + m_2}. $$

Typical vibrational energies \(\hbar \omega_0\) range from 0.2 - 0.5 eV, corresponding to spectral lines in the infrared.

Even at the ground vibrational state (\(v =0\), a molecule still has a zero point energy $$ \frac{1}{2} \hbar \omega_0 $$

Rotational Transitions

Due to quantization of rotational angular momentum as the molecule rotates about the axis perpendicular to the internuclear axis.

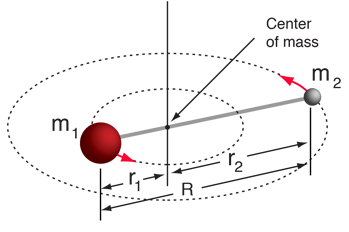

Moment of inertia for a diatomic molecule. Credit: Hyperphysics

Has rotation quantum number \(J\) and rotational energy levels $$ E_\mathrm{rot}(J) = \frac{\hbar}{2I}J(J +1) $$ where \(I\) is the molecule’s moment of inertia. Typical rotational levels have energy differences approximately 100x smaller than vibrational levels, so each vibrational level is usually split into many rotational sub-levels.

Moment of inertia given by $$ I = m_1 r_1^2 + m_2 r_2^2 = \mu R^2 $$

One would specify a transition using a combination of quantum numbers, like $$ {}^{12}\mathrm{CO}\,v=0; J=1-0 $$ a purely rotational transition.

Electronic transitions

Molecules can also have electronic transitions (i.e., w/ electrons), just like in atoms. And these typically have energies of a few eV and produce spectral lines in UV, optical and near-IR. Generally, though, when we’re talking about observations of (diatomic) molecular spectra, we’re usually dealing with rotational (radio) and sometimes vibrational (IR) transitions.