Radiative Transfer

- Draine Ch. 7

- Ryden and Pogge: Ch 2.1: The Equation of Radiative Transfer

- Ryden and Pogge: Ch 3.2: Radiative Transfer of Line Emission

- Lecture notes on Radiative Transfer in Astrophysics by C.P. Dullemond.

- Radiative Processes by Rybicki and Lightman, particularly Ch. 1

Radiative transfer describes the propagation of radiation through absorbing and emitting media.

In Wednesday’s lecture, we introduced specific intensity \(I_\nu\) and photon occupation number \(n_\gamma(\nu)\).

Photon occupation number $$ n_\gamma(\nu) = \frac{c^2}{2 h \nu^3} I_\nu $$ “dimensionless” number of photons per mode per polarization (per solid angle per frequency bin).

In LTE (blackbody), $$ I_\nu = B_\nu(T) = \frac{2 h\nu^3}{\exp(h \nu / kT) - 1} $$ and $$ n_\gamma = \frac{1}{\exp(h \nu / k T) - 1}. $$

Gallery of temperatures!

Now don’t assume LTE

- Brightness temperature \(T_B(\nu)\) (units K) is a way to characterize a specific intensity (or surface brightness). Given some specific intensity \(I_\nu\), it is defined as the temperature such that a blackbody at that temperature has that specific intensity, i.e., $$ T_B(\nu) = \frac{h \nu / k}{\ln[1 + 2 h \nu^3/c^2 I_\nu]} $$

On it’s own, quoting a brightness temperature says nothing about whether the astrophysical source is in LTE. In fact, brightness temperature is commonly used to describe sources that are far from LTE or isotropic (masers, GRBs, etc.) You could alternatively describe the specific intensity (or surface brightness) in units of Jy/ster, for example, since that is what the Planck function provides (given some temperature).

- Antenna temperature \(T_A\) (units K) is just like brightness temperature, only we make the assumption that we’re in the Rayleigh-Jeans limit of \(k T_A \gg h \nu\) or \(n_\gamma \gg 1\) so we have $$ T_A(\nu) = \frac{c^2}{2 k \nu^2} I_\nu $$

Again, an antenna temperature says nothing about whether the astrophysical source is in LTE, it is a convenient way to describe a specific intensity or surface brightness. If you’re going to use temperature as a shorthand for specific intensity (without needing to appeal to LTE temperature), antenna temperature is a good one to use because it is linear in intensity.

BUT, if a source is in LTE with temperature \(T\), then we will have \(T_B = T\), and if we’re observing at radio wavelengths, \(T_A \approx T\) as well.

Remember from last lecture we said that in LTE we could calculate the relative level populations between two states using the Boltzmann distribution $$ \frac{n_u}{n_l} = \frac{g_u}{g_l}e^{(E_l - E_u)/kT} $$ Given some relative population of two levels, we can define a quantity called excitation temperature $$ \frac{n_u}{n_l} = \frac{g_u}{g_l}e^{(E_l - E_u)/kT_\mathrm{exc}}. $$ So an excitation temperature (in K) is a way to communicate the relative population of two levels. In LTE, \(T_\mathrm{exc} = T\).

Radiative transfer

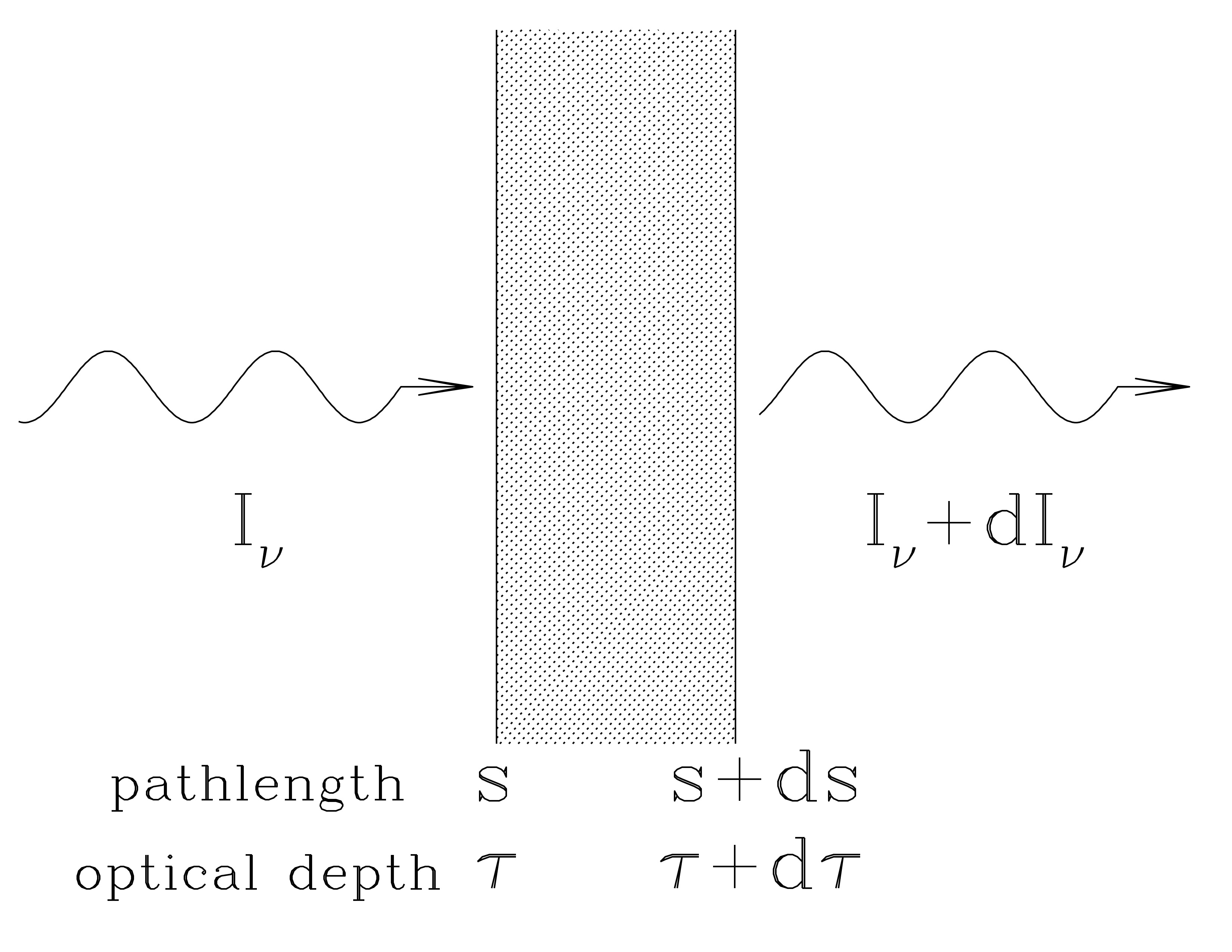

Draine Figure 7.1. Geometry for radiative transfer.

Equation of radiative transfer. Consider a ray or beam of radiation. Neglect scattering. $$ d I_\nu = - I_\nu \kappa_\nu ds + j_\nu ds $$

- The first term is the net change in \(I_\nu\) due to absorption and stimulated emission.

- The second term is the change in \(I_\nu\) due to spontaneous emission by the material in the path of the beam

Emission and absorption coefficients

- \(\kappa_\nu\) is attenuation coefficient, and has dimensions of [1/cm]. Usually positive, except for masers/lasers, where it’s negative. Rybicki and Lightman call this \(\alpha_\nu\).

- \(j_\nu\) is emissivity, with units power per unit volume per frequency per unit solid angle

For something with energy levels (and randomly oriented in space) $$ j_\nu = \frac{1}{4 \pi} n_u A_{ul} h \nu \phi_\nu $$ where \(\phi_\nu\) is the normalized line profile from the previous lecture.

Attenuation coefficient is proportional to the net absorption, which is true absorption minus stimulated emission $$ \kappa_\nu = n_l \sigma_{l \rightarrow u}(\nu) - n_u \sigma_{u \rightarrow l}(\nu) $$ $$ \kappa_\nu = n_l \sigma_{l \rightarrow u}(\nu) \left [ 1 - \frac{n_u/n_l}{g_u/g_l} \right] $$ $$ \kappa_\nu = n_l \sigma_{l \rightarrow u}(\nu) \left [ 1 - e^{-h \nu/k T_\mathrm{exc}} \right] $$

Integrating the Radiative Transfer Equation

You can do this as a function of pathlength, \(s\). E.g., carry out this numerically using an ODE solver.

But, given the way absorption and emission works, it’s often very helpful to do a change of variables to an optical depth, \(\tau\). The differential optical depth is defined as $$ d \tau_\nu = \kappa_\nu ds $$ this definition assumes radiation propagates in the direction of increasing \(\tau\), and the radiative transfer equation becomes $$ d I_\nu = - I_\nu d \tau_\nu + S_\nu d \tau_\nu $$ where the source function is $$ S_\nu = \frac{j_\nu}{\kappa_\nu} $$

Remember, no scattering included

Again, you can solve radiative transfer problems using this ODE as is.

We can also get another useful form by using integrating factors to formally integrate the equation

$$ e^{\tau_\nu} (d I_\nu + I_\nu d \tau_\nu) = e^{\tau_\nu} S_\nu d \tau_\nu $$

$$ d(e^{\tau_\nu} I_\nu) = e^{\tau_\nu} S_\nu d \tau_\nu $$

Choose some boundary condition \(\tau_\nu = 0\) with initial value \(I_\nu(0)\) $$ e^{\tau}I_\nu - I_\nu(0) = \int_0^{\tau_\nu} e^{\tau^\prime} S_\nu d \tau^\prime $$ multiply through by \(e^{-\tau_\nu}\) and we have the equation of radiative transfer in integral form $$ I_\nu(\tau_\nu) = I_\nu(0)e^{-\tau_\nu} + \int_0^{\tau_\nu} e^{-(\tau_\nu - \tau^\prime)}S_\nu d \tau^\prime $$ \(S_\nu\) can be a function of position.

Interpretation: the intensity at some optical depth \(\tau_\nu\) is

- the initial intensity \(I_\nu(0)\) attenuated by a factor \(e^{-\tau}\)

- plus the integral over the emission \(S_\nu d \tau^\prime\) attenuated by the factor \(e^{-(\tau_\nu - \tau^\prime)}\) due to the effective emission from the point of emission.

When scattering is present, \(S_\nu\) contains a contribution from \(I_\nu\), so you cannot specify \(S_\nu\) a priori. Iterative schemes may be needed to solve to convergence (see modern RT packages).

Uniform medium

Slab of uniform medium, energy levels populated according to a single excitation temperature \(T_\mathrm{exc}\), and the system is in LTE, so $$ I_\nu = B_\nu(T_\mathrm{exc}) = S_\nu. $$ If the system is in LTE, why must \(S_\nu = B_\nu\)? Otherwise the presence of the material would alter the radiation, and the system would not be in thermal equilibrium (but, by definition, it already is).

Then the RTE becomes $$ 0 = d I_\nu = - B_\nu d \tau_\nu + S_\nu d \tau_\nu $$

In LTE, \(j_\nu\) and \(\kappa_\nu\) only depend on the local properties of the matter. Then we can solve $$ I_\nu = I_\nu(0) e^{-\tau_\nu} + B_\nu(T_\mathrm{exc})(1 - e^{-\tau_\nu}) $$

Think about what happens as we grow \(\tau_\nu\).

- at \(\tau_\nu \approx 0\), we retain \(I_\nu(0)\)

- at \(\tau \gg 1\), we obtain \(S_\nu = B_\nu\)

You can also reverse the coordinates.

Let’s talk about which pathlengths in this image (from the camera to the ground) are “optically thick” or “optically thin.”

There’s scattering by water droplets here, so it’s not a perfect analogy. But the idea about optical depth is still relevant.

Maser lines

Radiative pumping (discussed later) can set up relative level populations $$ n_u > \frac{g_u}{g_l} n_l $$

- the excitation temperature goes negative(!)

- we have a population inversion

- stimulated emission is stronger than absorption

- radiation is amplified as it propagates

Masing happens for microwave transitions of H I, OH, H2O, and SiO. Some masers have brightness/antenna temperatures of \(T_A > 10^{11}\)K.

This means they would have a HUGE flux if they were as spatially extended as other astronomical sources. But the \(d\Omega\) is typically small.