H I 21-cm Emission and Absorption

- Draine Ch. 8

- Ryden and Pogge Ch. 3.1: 21cm Emission and Absorption

- Ryden and Pogge Ch. 3.3: Exciting Hyperfine Energy Levels

This is the first lecture where we’re moving a bit from the core processes and moving back towards a discussion of the many “phases” of the ISM.

Just as a review, we had (according to Draine):

- Coronal gas, “hot ionized medium” or “HIM”

- H II gas, dense H II regions, diffuse H II regions, “warm ionized medium” or “WIM”

- Warm H I, “warm neutral medium” or “WNM”

- Cool H I, “cold neutral medium” or “CNM”

- Diffuse molecular gas

- Dense molecular gas

- Stellar outflows

So, in talking about H I emission and absorption, we’re primarily talking about the warm neutral medium (R&P Ch 3) and the cold neutral medium (R&P Ch 2). We’re following Draine in a linear manner; these concepts are swapped slightly in R&P.

ISM phases are ionization state, density, and temperature.

Cold neutral medium: absorption lines (from previous lectures, will also be covered in Friday’s lecture). T approx 100 K, \(n_H = 30 \;\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\) and neutral. Volume fraction of 1%.

Warm Neutral Medium: T approx 5000 K, \(n_H = 0.6\;\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\) and neutral. Volume fraction of 40%.

Taken together, cold neutral medium and warm neutral medium contain over half of the mass of the Milky Way Galaxy’s ISM. Observationally, we can study this neutral atomic hydrogen directly via the hyperfine transition.

- mapping distribution of H I in MW and other galaxies

- galactic rotation curve

- gas temperatures in interstellar clouds

H I emissivity and absorption coefficient

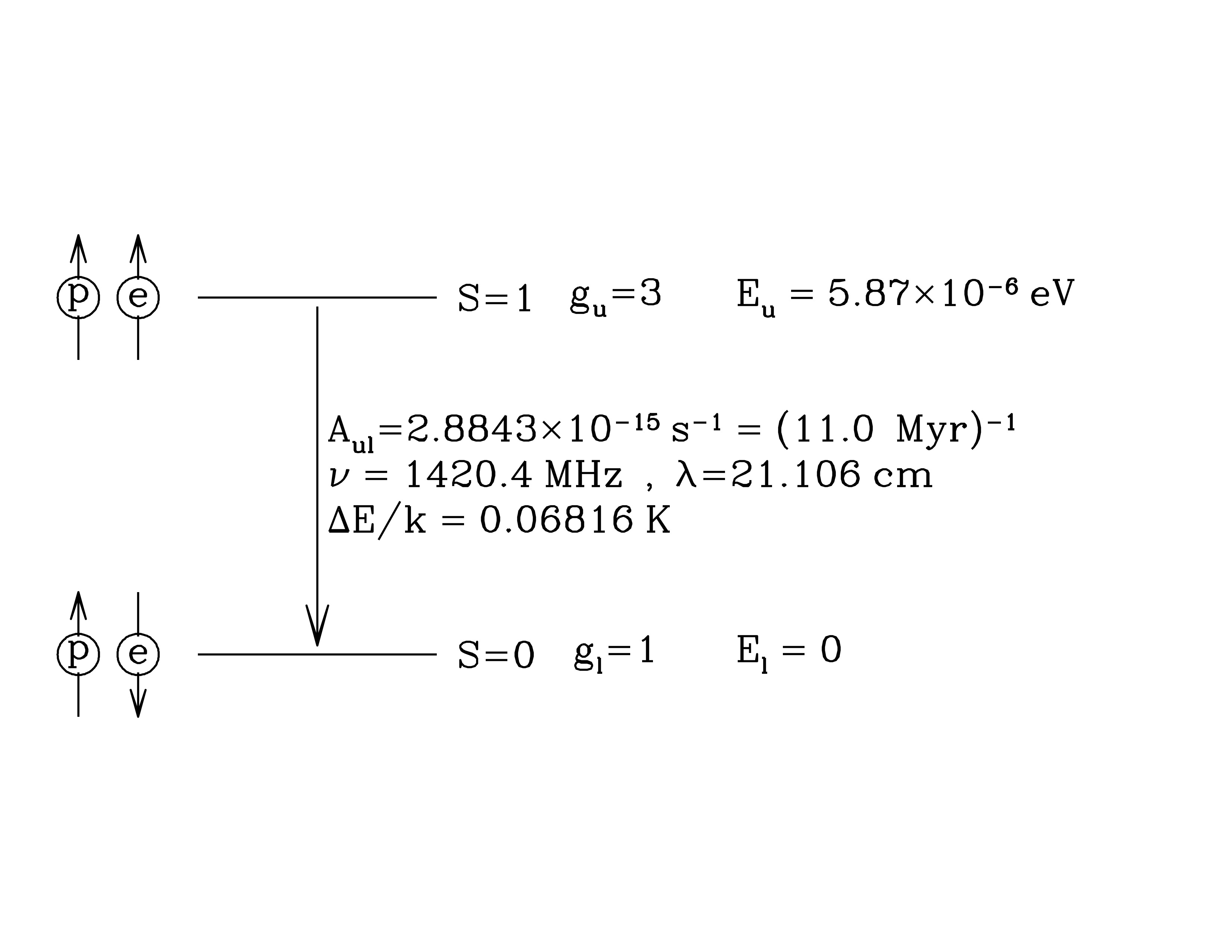

Hyperfine splitting of the 1s ground state of atomic H Credit: Figure 8.1: Draine.

Magnetic moment of electron coupled to magnetic moment of proton creates a “hyperfine” split between the parallel and antiparallel spin states.

Anti-parallel state

- has lower energy \(E_l = 0\)

- degeneracy \(g_l = 1\)

Parallel state

- total spin \(S = 1\), degeneracy \( g_u = 2 S + 1 = 3\)

- \(E_u - E_l = 5.87\times10^{-6}\) eV

When the electron drops from parallel to anti-parallel states, the photon emitted has wavelength $$ \lambda = \frac{h c}{E_u - E_l} = 21.11\,\mathrm{cm} $$

Let’s think a little bit about how this transition gets populated. Using the same concept of excitation temperature, but here we’re going to call it spin temperature $$ \frac{n_u}{n_l} = \frac{g_u}{g_l}e^{(E_l - E_u)/kT_\mathrm{spin}}. $$ We can plug in the values for the spin flip transition and simplify the equation and $$ \frac{E_l - E_u}{k} = 0.0682\;\mathrm{K}. $$ is the temperature corresponding to the energy of the spin flip transition. Then the relative population levels are $$ \frac{n_u}{n_l} = 3 e^{-0.0682\;\mathrm{K}/T_\mathrm{spin}}, $$

How does \( e^{-0.0682\;\mathrm{K}/T_\mathrm{spin}}\) behave? Unless \(T_\mathrm{spin} \lesssim 0.0682\;\mathrm{K}\), the exponent is approximately zero, and \(e^0 = 1\). We can explore this relationship for a range of spin temperatures, and we see that \(n_u/n_l \approx 3\) for all but the very coldest spin temperatures.

Thinking about material out there in space, can someone tell me the coldest something is likely to be if it’s just sitting out there in interstellar space, even close to LTE? The CMB puts a pretty good lower bound on \(T\) so long as nothing funny is happening, since \(T_\mathrm{CMB} = 2.725\;\mathrm{K}\).

Even the average CMB photon is much more energetic than this, \(T_\mathrm{CMB} = 2.725\;\mathrm{K}\), so these upper levels can be and are easily populated!

Emissivity

So we reach the interesting conclusion that the level populations of H I 21cm transitions are $$ n_u \approx \frac{3}{4} n(\mathrm{H\;I}) $$ $$ n_l \approx \frac{1}{4} n(\mathrm{H\;I}) $$ independent of any astrophysically practical spin temperatures. Because the upper level always contains approximatel 75% of the H I, this means that the H I 21cm emissivity is also independent of the spin temperature, and we have $$ j_\nu = n_u \frac{A_{ul}}{4 \pi} h \nu_{ul} \phi_\nu = \frac{3}{16\pi} A_{ul} h \nu_{ul} n(\mathrm{H\;I}) \phi_\nu. $$

Absorption coefficient

Following similar manipulations we covered in Draine Chs. 6 and 7, we can write the absorption coefficient $$ \kappa_\nu = n_l \sigma_{lu} - n_u |\sigma_{ul}| $$ $$ \kappa_\nu = n_l \frac{g_u}{g_l} \frac{A_{ul}}{8 \pi} \lambda_{ul}^2 \phi_\nu \left [ 1 - \frac{n_u}{n_l} \frac{g_l}{g_u} \right] $$ $$ \kappa_\nu = n_l \frac{g_u}{g_l} \frac{A_{ul}}{8 \pi} \lambda_{ul}^2 \phi_\nu \left [ 1 - e^{-h \nu_{ul} / k T_\mathrm{spin}} \right] $$ as we just discussed, \( e^{-h \nu_{ul} / k T_\mathrm{spin}} \approx 1\).

What does \(\kappa_\nu\) represent? It’s the net absorption coefficient, meaning it’s the true (total) absorption minus the contribution from stimulated emission.

If we have \( e^{-h \nu_{ul} / k T_\mathrm{spin}} \approx 1\), the upper state is going to fairly populated, so what does that say about stimulated emission? It means that it is significant and we need to include it in our calculations.

Using the small x approximation \(e^{-x} \approx 1 - x\) for \(x \ll 1\), we can finally simplify to $$ \kappa_\nu \approx \frac{3}{32 \pi} A_{ul} \frac{h c \lambda_{ul}}{k T_\mathrm{spin}} n(\mathrm{H\;I}) \phi_\nu $$ and we find that the absorption coefficient depends on spin temperature like $$ \kappa_\nu \propto \frac{1}{T_\mathrm{spin}} $$ i.e., it gets large when the spin temperature is low and the lower level is populated (subject to our assumption that \(h \nu_{ul} / k T_\mathrm{spin} \ll 1\) for the conditions of interest).

If the spin temperature gets very high, we aren’t going to have much net absorption (\(\kappa_\nu \approx 0 \)), because every truly absorbed photon will be balanced out by one contributed from stimulated emission.

Example calculation

Assume a Gaussian internal velocity distribution for the H I cloud with dispersion \(\sigma_V\). Assume we are looking at a frequency \(\nu\), which corresponds to a Doppler shift of \(u\), where $$ \nu = \nu_{ul}(1 - u/c) $$ and yields a normalized line profile of $$ \phi_\nu = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \frac{c}{\nu_{ul}} \frac{1}{\sigma_V}e^{-u^2/2 \sigma_V^2} $$ The absorption coefficient is $$ \kappa_\nu = 2.190\times10^{-19}\;\mathrm{cm}^2\;n(\mathrm{H\;I}) \frac{K}{T_\mathrm{spin}} \frac{\mathrm{km\;s}^{-1}}{\sigma_V} e^{-u^2/2 \sigma^2_V}. $$ We can find optical depth $$ d\tau = \kappa_\nu ds. $$ Let’s assume the properties of the cloud (spin temp, velocity dispersion) are constant along the line of sight, and write down column density as $$ N(\mathrm{H\;I}) = \int n(\mathrm{H\;I}) ds $$ then we have, $$ \tau_\nu = 2.190 \frac{N(\mathrm{H\;I})}{10^{21}\;\mathrm{cm}^{-2}} \frac{100\;\mathrm{K}}{T_\mathrm{spin}} \frac{\mathrm{km\;s}^{-1}}{\sigma_V} e^{-u^2/2 \sigma_V^2}. $$ What column density do we need for the line of sight to be marginally optically thick (\( \tau_\nu \gtrsim 1\))?

Many sightlines have \(N(\mathrm{H\;I}) \gtrsim 10^{21}\;\mathrm{cm}^{-2}\), spin temperatures of \(T_\mathrm{spin} \approx 10^2\;\mathrm{K}\), and velocity dispersions of a few km/s, which means self-absorption of the 21-cm line can be important.

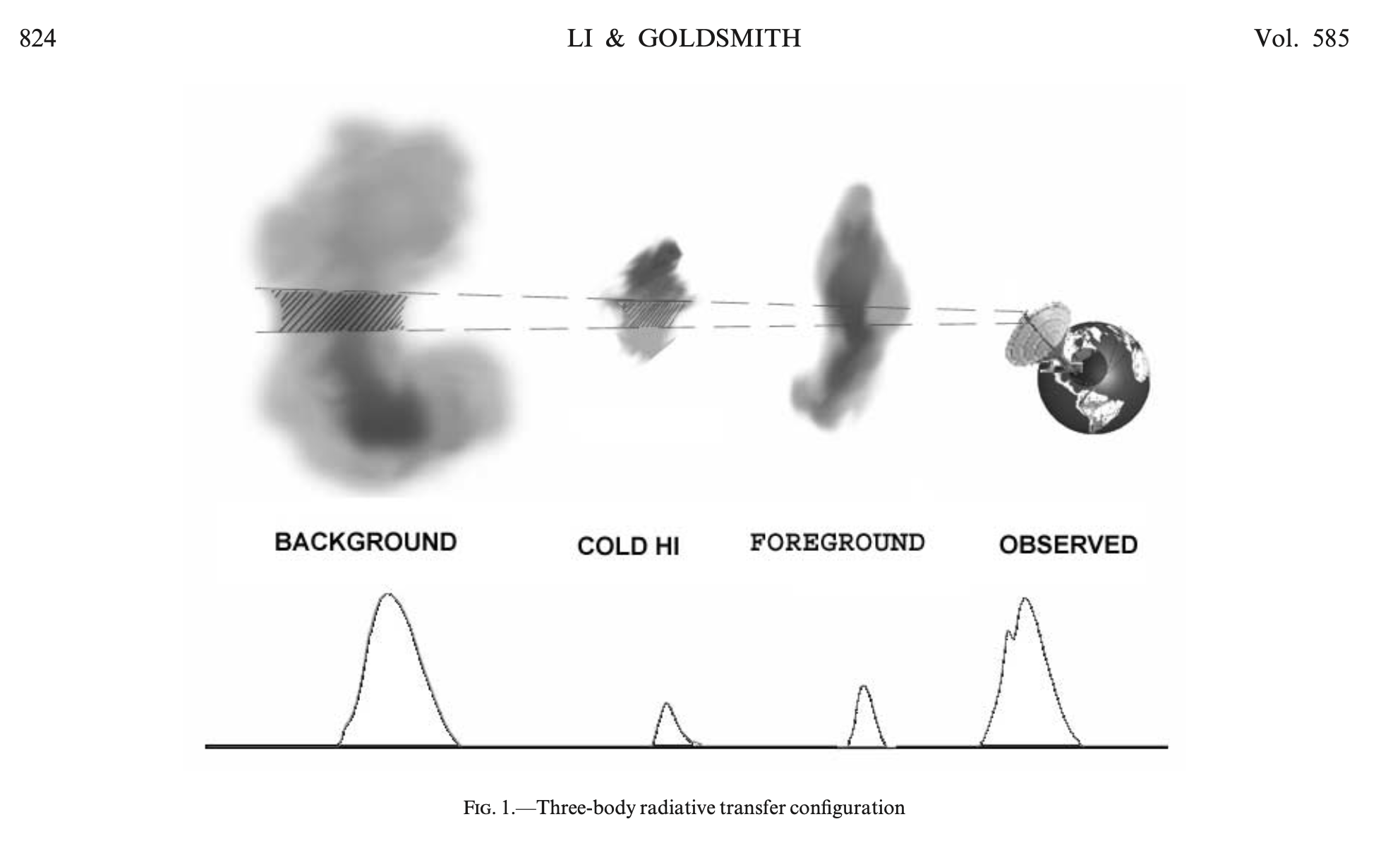

Self-absorption. A foreground cloud will appear darker than a background cloud. Think of this in the line profiles, where you can have small dips on top of a larger line plots.

Figure 1. Credit: Li and Goldsmith 2003

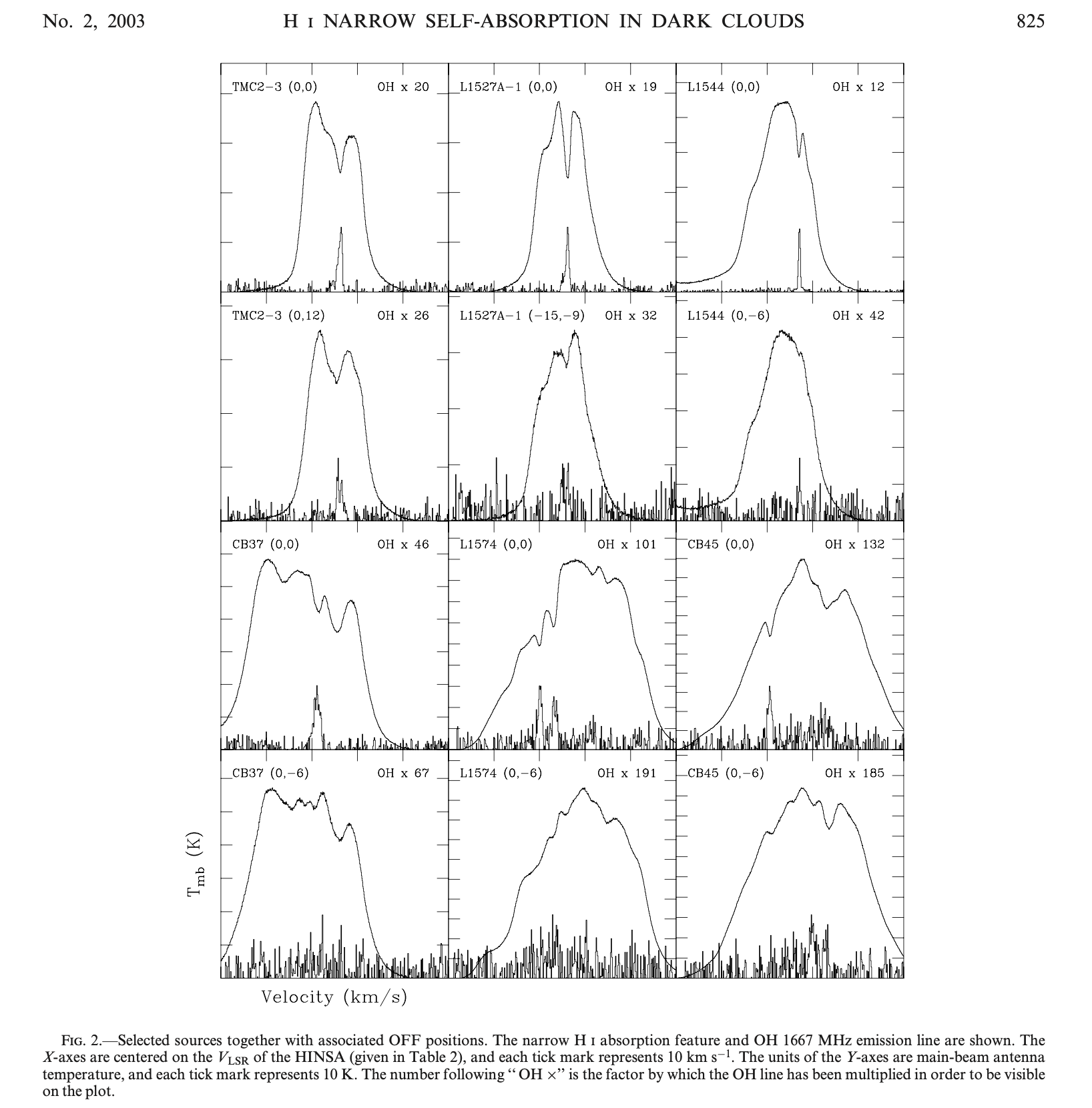

Figure 2. Credit: Li and Goldsmith 2003

The Li and Goldsmith paper.

Optically Thin Cloud

Assume a cloud with $$ N(\mathrm{H\;I}) \lesssim 10^{20}\,\mathrm{cm}^{-2}\frac{T_\mathrm{spin}}{100\,\mathrm{K}} \frac{\sigma_V}{\mathrm{km\;s}^{-1}} $$ such that \(\tau_\nu \lesssim 0.2\) even at line center (i.e., it’s optically thin).

- Assume that we can neglect absorption. How would we calculate the emergent intensity \(I_\nu\) from this cloud, using the equation of radiative transfer?

Using the path length formulation, $$ I_\nu = I_\nu(0) + \int j_\nu ds. $$ Let’s take our equation for \(j_\nu\) from before, assume constant properties along the ray, and use the idea that $$ N(\mathrm{H\;I}) = \int n(\mathrm{H\;I}) ds $$ we have $$ I_\nu = I_\nu(0) + \frac{3}{16\pi}A_{ul} h \nu_{ul} \phi_\nu N(\mathrm{H\;I}). $$ Assume we know \(I_\nu(0)\) from somewhere else. Rearrange and calculate the intensity contribution from the cloud, over all frequencies $$ \int \left [ I_\nu - I_\nu(0) \right] d \nu = \frac{3}{16\pi}A_{ul} h \nu_{ul} N(\mathrm{H\;I}) $$ because we know \(\int \phi_\nu d\nu = 1\).

Let’s rewrite this using antenna temperature and relative velocity \(u\) $$ \int \left [ T_A - T_A(0) \right] du = \int \frac{c^2}{2 k \nu^2} \left [I_\nu - I_\nu(0) \right] \frac{c}{\nu} d\nu $$ $$ \int \left [ T_A - T_A(0) \right] du = 54.89\;\mathrm{K\;km\;s}^{-1} \frac{N(\mathrm{H\;I})}{10^{20}\;\mathrm{cm}^{-2}} $$ This relationship allows us to

- make an integrated line intensity measurement of 21-cm emission

- calculate the total H I column density \(N(\mathrm{H\;I})\)

- without needing to know \(T_\mathrm{spin}\)! (as long as self-absorption not important)

If we can assume optically thin emission, we can even estimate the total H I mass in another galaxy.

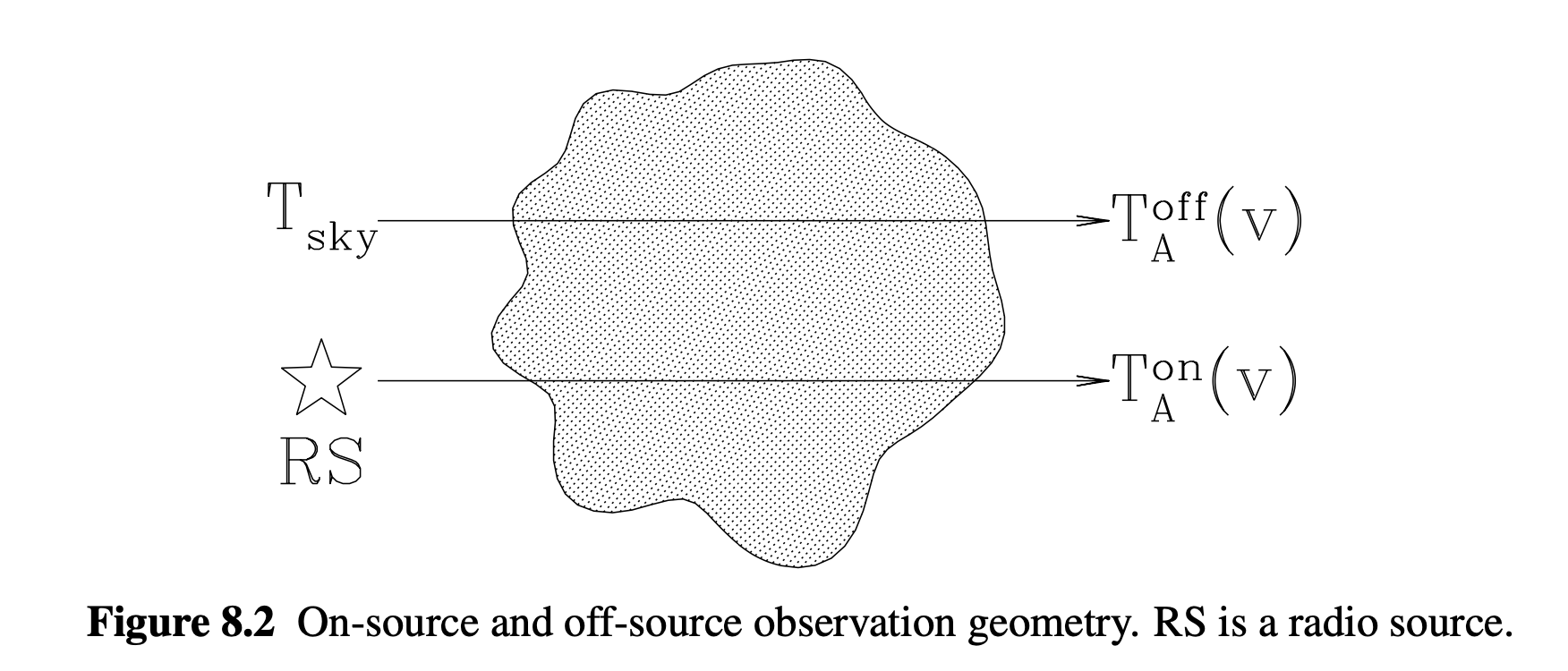

Spin temperature determination using background radio sources

Credit: Draine

Assumptions

- we have a bright background radio source with a “known” continuum spectrum \(T_\mathrm{RS}\), or at least known that it should be intrinsically flat within some frequency range

- cloud (ISM) properties are uniform across the two sightlines: \(N(\mathrm{H\;I})\) and \(T_\mathrm{spin}\)

- nothing behind the “off” sightline, just blank sky whose antenna temperature \(T_\mathrm{sky}\) we can measure/approximate from nearby measurements in space and frequency.

Using the fact that specific intensity and antenna temperature have a linear relationship, take the RTE in integral form and write down the relationships between all of the temperatures in the Figure, assuming a radial velocity \(v\). $$ T_A^\mathrm{off}(v) = T_\mathrm{sky}e^{-\tau_\nu} + T_\mathrm{spin}(1 - e^{-\tau_\nu}) $$ and $$ T_A^\mathrm{on}(v) = T_\mathrm{RS} e^{-\tau_\nu} + T_\mathrm{spin}(1 - e^{-\tau_\nu}). $$ Then, solve for \(\tau_\nu\) and \(T_\mathrm{spin}\) $$ \tau(v) = \ln \left [ \frac{T_\mathrm{RS} - T_\mathrm{sky}}{T_A^\mathrm{on}(v) - T_A^\mathrm{off}} \right] $$ and $$ T_\mathrm{spin} = \frac{T_A^\mathrm{off}(v) T_\mathrm{RS} - T_A^\mathrm{on}(v) T_\mathrm{sky}}{(T_\mathrm{RS} - T_\mathrm{sky}) - [T_A^\mathrm{on}(v) - T_A^\mathrm{off}(v)]}. $$ When absorption is strong,

- \(T_\mathrm{RS} - T_\mathrm{sky}\) is measurably larger than \(T_A^\mathrm{on}(v) - T_A^\mathrm{off}\)

- can calculate \(\tau_\nu\) and \(T_\mathrm{spin}\)

If absorption is weak,

- can’t tell the difference between \(T_\mathrm{RS} - T_\mathrm{sky}\) vs. \(T_A^\mathrm{on}(v) - T_A^\mathrm{off}\)

- upper limit on \(\tau (v)\) and lower limit on \(T_\mathrm{spin}(v)\).