Emission and Absorption by a Thermal Plasma

- Draine Ch. 10

- Rybicki and Lightman Ch 5.

- Ryden and Pogge, Chs. 4.1, 4.3

A thermal plasma is a partially ionized gas, whose particles have a velocity distribution that are very close to Maxwellian. We see these in interstellar space, with temperatures \(T = 10^3 - 10^8\) K. Generally, we can treat the plasma as in LTE.

Note, though, that in the following discussion “continuum” does not necessarily mean blackbody, it just means that the opacity of the transition is much broader in frequency than a spectral line transition.

Three important emission mechanisms in plasmas

- Free-free transitions: an electron is inelastically scattered from one free state to another, emitting a continuum photon

- Free-bound transitions: an electron is initally free, but is captured into a bound state, emitting a continuum photon

- Bound-bound transitions: an electron makes a transition from one bound state to another, which the change in energy carried away by one or two photons

Today we are discussing 1 and 2. 3 will be discussed the following week in lectures on “Recombination of Ions with Electrons” and “Collisional Excitation.”

Free-Free emission (Bremsstrahlung)

“Braking radiation”

- Classical electromagnetism: an accelerating charge radiates electromagnetic energy.

- in a thermal plasma (remember, hot & partially ionized), electrons and ions are scattering off of one another

- because the electrons are much lighter than the ions, they undergo larger accelerations and dominate the radiation

Provides continuum emission from radio frequencies up to the point where the photon energies are comparable to the thermal energy \(k T\).

See Rybicki and Lightman Ch 5: Bremsstrahlung for more details on the derivation of the emissivity of this mechanism. Here, we’ll just write down the result $$ j_{\mathrm{ff}, \nu} = \frac{8}{3} \left ( \frac{2 \pi}{3} \right)^{1/2} g_{\mathrm{ff}, i} \frac{e^6}{m_e^2 c^3} \left ( \frac{m_e}{kT} \right)^{1/2} e^{- h \nu / k T} n_e Z_i^2 n_i $$ $$ j_{\mathrm{ff}, \nu} = 5.444 \times 10^{-41} g_\mathrm{ff} T_4^{-1/2} e^{- h \nu / k T} Z_i^2 n_i n_e \;\mathrm{erg}\;\mathrm{cm}^3\;\mathrm{s}^{-1}\;\mathrm{sr}^{-1}\;\mathrm{Hz}^{-1} $$ here \(n_i\) represents the ions, and \(n_e\) represents the electrons.

\(g_{\mathrm{ff},i}(\nu, T)\) is the Gaunt factor for free-free transitions. When doing classical physics, Gaunt factor = 1. It’s different from 1 when we need to treat quantum mechanical effects. Even then, the correction factor is only 1 order of magnitude different from 1, across a wide range of frequencies.

If we assume that \(g_{\mathrm{ff},i}(\nu, T)\) is constant (w \(\nu\)), then the emissivity is flat (independent) with frequency at low frequencies.

We can calculate the power radiated per volume as $$ \Lambda_\mathrm{ff} = 4 \pi \int_0^\infty j_{\mathrm{ff},\nu} d \nu $$ and we get that $$ \Lambda_\mathrm{ff} \propto n_i n_e \sqrt{T} $$

See Draine 10.2 and 10.3 for how to properly calculate and average over the Gaunt factor for various regimes.

Free-free absorption

If we have a thermal distribution, then Kirchoff’s law must be satisfied $$ B_\nu = \frac{j_\nu}{\kappa_\nu} $$ where \(B_\nu\) is the Planck function. Kirchoff’s law is a neat trick, because we can go calculate the attenuation coefficient \(\kappa_\nu\) from the emissivity \(j_\nu\).

$$ \kappa_{\mathrm{ff},\nu} = \frac{4}{3} \left ( \frac{2 \pi}{3} \right)^{1/2} \frac{e^6}{m_e{3/2} (k T)^{1/2} h c \nu^3} \left [ 1 - e^{- h \nu / k T} \right] Z_i^2 n_i n_e g_\mathrm{ff} $$

from the frequency dependence, we see that free-free absorption becomes strong at low (radio) frequencies.

Emission Measure

Calculate the intensity \(I_\nu\) from free-free emission from an ionized region $$ I_\nu(s) = I_\nu(0) e^{-\tau_\nu} + \int_0^s d s^\prime j_{\mathrm{ff},\nu} e^{-[\tau_\nu(s) - \tau_nu(s^\prime)]} $$ $$ I_\nu(s) = I_\nu(0) e^{-\tau_\nu} + \int_0^{\tau_\nu} d \tau^\prime \left [ \frac{j_{\mathrm{ff}, \nu}}{\kappa_{\mathrm{ff}, \nu}} \right] e^{-(\tau - \tau^\prime)} $$ If the region has a uniform temperature, then the integral becomes $$ I_\nu = I_\nu(0) e^{-\tau_\nu} + \left [ \frac{j_{\mathrm{ff}, \nu}}{\kappa_{\mathrm{ff}, \nu}} \right]T (1 - e^{-\tau\nu}) $$

Now let’s define something called the emission measure $$ EM = \int n_e n_p ds = \left [ \frac{n_e n_p}{\kappa_{\mathrm{ff},\nu}} \right ]T \tau\nu. $$ Since most clouds are net neutral, we can write $$ EM \approx \int n_e^2 ds. $$

We can rewrite the RTE, $$ I_\nu = I_\nu(0) e^{-\tau_\nu} + \frac{(1 - e^{-\tau_\nu})}{\tau_\nu} \left [ \frac{j_{\mathrm{ff},\nu}}{n_e n_p} \right ]T EM $$ when we are very optically thin (\(\tau \ll 1 \)), we have $$ \frac{(1 - e^{-\tau\nu})}{\tau_\nu} \approx 1. $$ We can plug back in for the Brehmsstralung emissivity and obtain the result that intensity increases linearly with EM. See Draine Ch 10.5 for prefactors.

For low frequencies \(\nu \leq 1 \) GHz, self-absorption can become important in dense H II regions. Generally negligible in other ISM settings.

Free-bound transitions: Recombination continuum

Electron captured by an ion, making the transition from a “free” state to a “bound” state, and emitting a photon.

How might we calculate the emissivity \(j_{\mathrm{fb},\nu}\) for this interaction, assuming LTE (i.e., thermal plasma)?

Let’s think about the tools that we need: \(\kappa_\nu\), \(B_\nu\), \(\sigma\), \(n_b\)

Here’s one way to go about it. In our second lecture on collisional processes, we used the impact approximation to approximately calculate the cross section for photoionization, \(\sigma_b\). We assumed there was an electron with some kinetic energy, it engaged in some momentum transfer with the atom, and this extra change in momentum unbound it’s own electron, ionizing the atom.

Then, we know that we can use our result from the radiative process lecture for net absorption $$ \kappa_\nu = n_l \sigma_{l \rightarrow u}(\nu) - n_u \sigma_{u \rightarrow l}(\nu) $$ to write $$ \kappa_\nu = n_l \sigma_b(\nu) \left [ 1 - e^{-h \nu/k T_\mathrm{exc}} \right]. $$

Next, let’s reuse Kirchoff’s law to relate $$ j_{\mathrm{fb}, \nu} = \kappa_{\mathrm{bf}, \nu} B_\nu(T) $$ and, since we are in LTE, \(T_\mathrm{exc} = T\), so $$ j_{\mathrm{fb}, \nu} = n_b \sigma_b(\nu) \left [ 1 - e^{-h \nu/k T} \right ] B_\nu(T) $$ where \(n_b\) is the number density of atoms in bound state b, if in LTE with electron density \(n_e\), and ion density \(n_i\). For example, \(n_b\) could be the number of hydrogen atoms with principle quantum number \(n=3\).

Finally, we would like to rewrite \(n_b\) in terms of the overall number densities of electrons and ions and the temperature of the plasma, because in a moment we’re going to want to consider multiple different bound states. To do this, we need to refer back to the statistical mechanics lecture and the law of mass action. One result from that lecture was the ability to take the reaction for photoionization $$ H(n) + e^- \leftrightarrow H^+ + 2e^- $$ and write down the relative number densities, obtaining

$$ \left [ \frac{n(H(n))}{n(H^+) n_e} \right]_\mathrm{LTE} = \left [ \frac{h^3}{(2 \pi k T)^{3/2}} \right] \left [ \frac{m_H}{m_p m_e} \right]^{3/2} \frac{g[H(n)]}{g(e^-) g(H^+)} e^{-I_n/kT} $$

where

$$ I_n = \frac{I_H}{n^2} $$

is the energy required to ionize \(H(n)\). Finally, putting it all together, we have

$$ j_{\mathrm{fb},\nu} = \frac{g_b}{2 g_i} \frac{h^4 \nu^3}{(2 \pi m_e k T)^{3/2} c^2} e^{(I_b - h \nu)/k T} \sigma_b(\nu) n_e n_i $$ where \(g_b\) is the degeneracy of the bound state, \(g_i\) is the degeneracy of the ion, and \(I_b\) is the energy required to ionize from bound state.

So, what did we do? We started with a photoionization cross section, related that to an absorption coefficient, used Kirchoff’s law and LTE assumptions to relate that to an emissivity, and then rewrote the number densities of the bound state \(n_b\) in terms of more-easily calculable quantities, \(n_e\) and \(n_i\).

Some take aways:

- Generally, the free-bound emissivity is proportional to $$ j_{\mathrm{fb},\nu} \propto n_e n_i. $$

- Each bound state contributes its own bit of recombination continuum starting at \(h \nu = I_b\), which is the minimum energy photon that can be emitted when an electron transitions from free to bound state b

- The recombination continuum tapers off at higher frequncies by the factor \(e^{(I_b - h \nu)/k T} \)

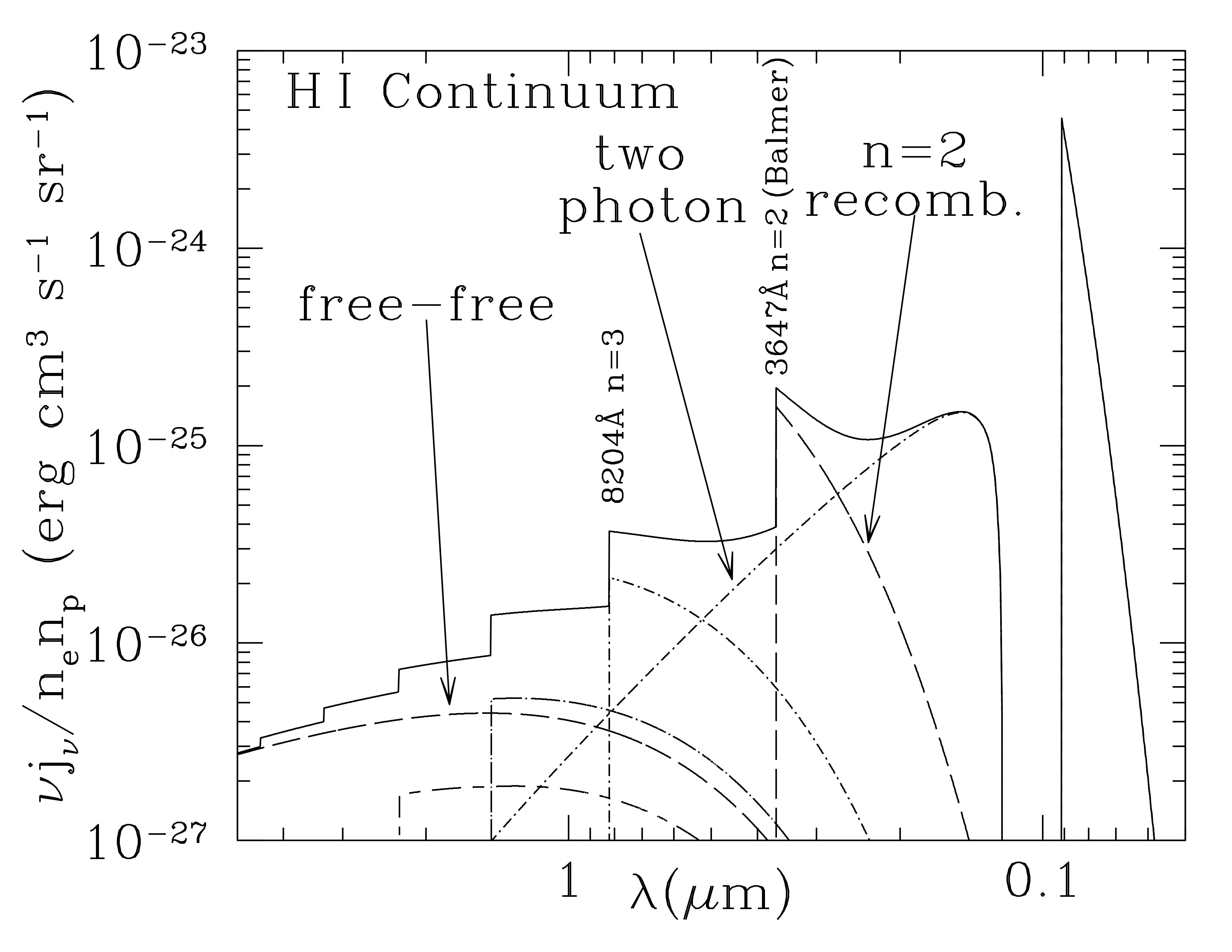

Now let’s examine this emission spectrum for a hydrogen plasma

Solid line is the continuous emission spectrum of a \(T=8000)) K hydrogen plasma, including free-free emission, recombination continuum emission, and two-photon emission. (Emission lines not shown). Notice the ‘semi-circle’ shape from the recombination emissivity. Credit: Draine Figure 10.2

Radio Recombination lines

Three-body collisional processes can populate hydrogen atoms with very high quantum states \(n \gtrsim 100\), which are also called Rydberg states. These high states can also undergo spontaneous decay to lower levels, such as the $$ n + 1 \rightarrow n $$ transitions we called the \(n\alpha\) transitions.