Interstellar Radiation Fields, Ionization Processes, and Recombination of Ions with Electrons

- Draine Ch. 12, 13, & 14

- Ryden and Pogge Ch 4

Interstellar Radiation Fields

- Draine Ch. 12

Pick a point in our galaxy, somewhere in the ISM. Look around. Unless you are deep in a molecular cloud, it isn’t completely dark.

Of course, the intensity of the incoming radiation very much depends on your location in the Galaxy and where you’re looking. Remember, \(I_\nu\) is a function of position \(\vec{x}\) and direction \(\Omega\).

If you’re very near an H II region, or partially shielded by a molecular cloud, etc… you will see a different spectrum.

The first part of this lecture is looking at the spectral energy distribution of the interstellar radiation field in a roughly “average” sense.

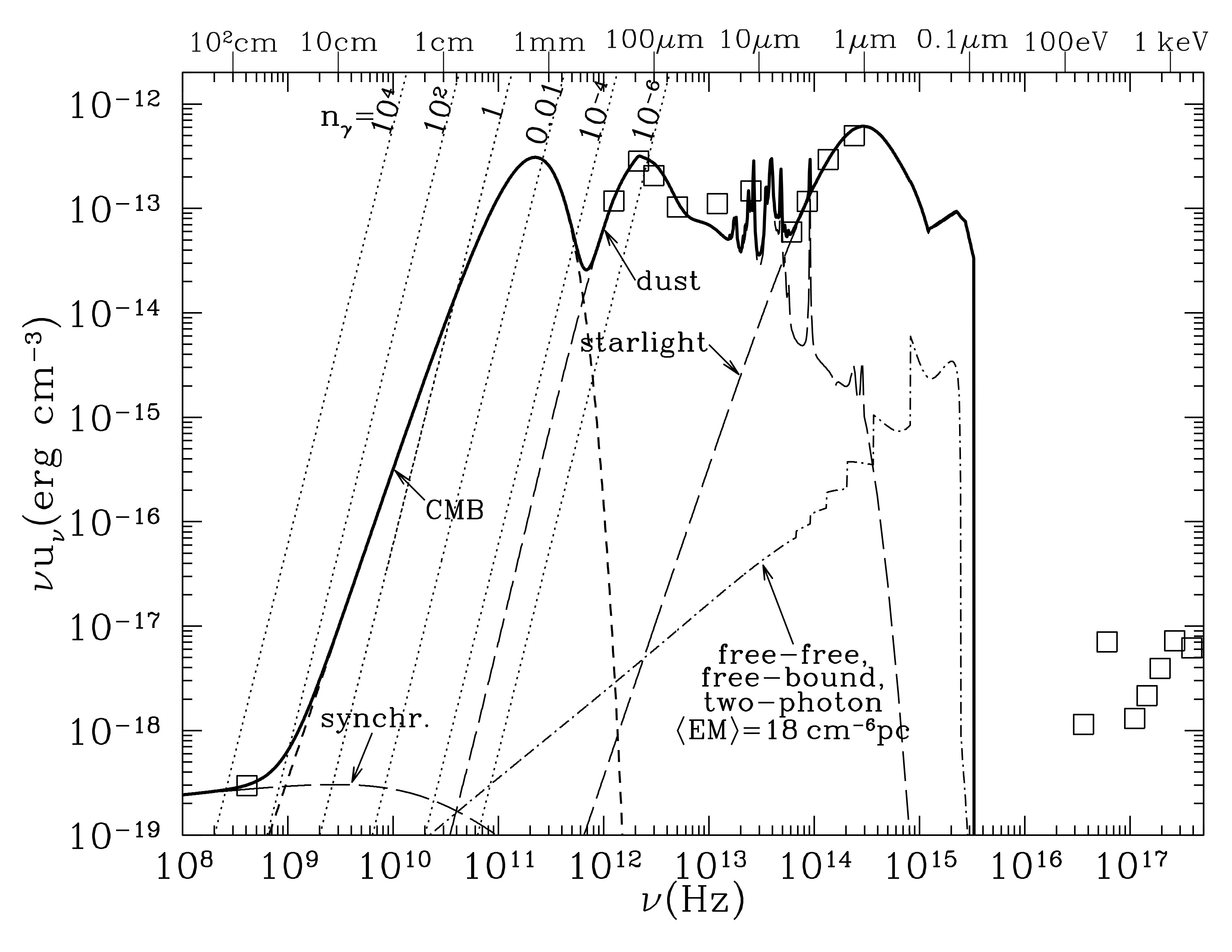

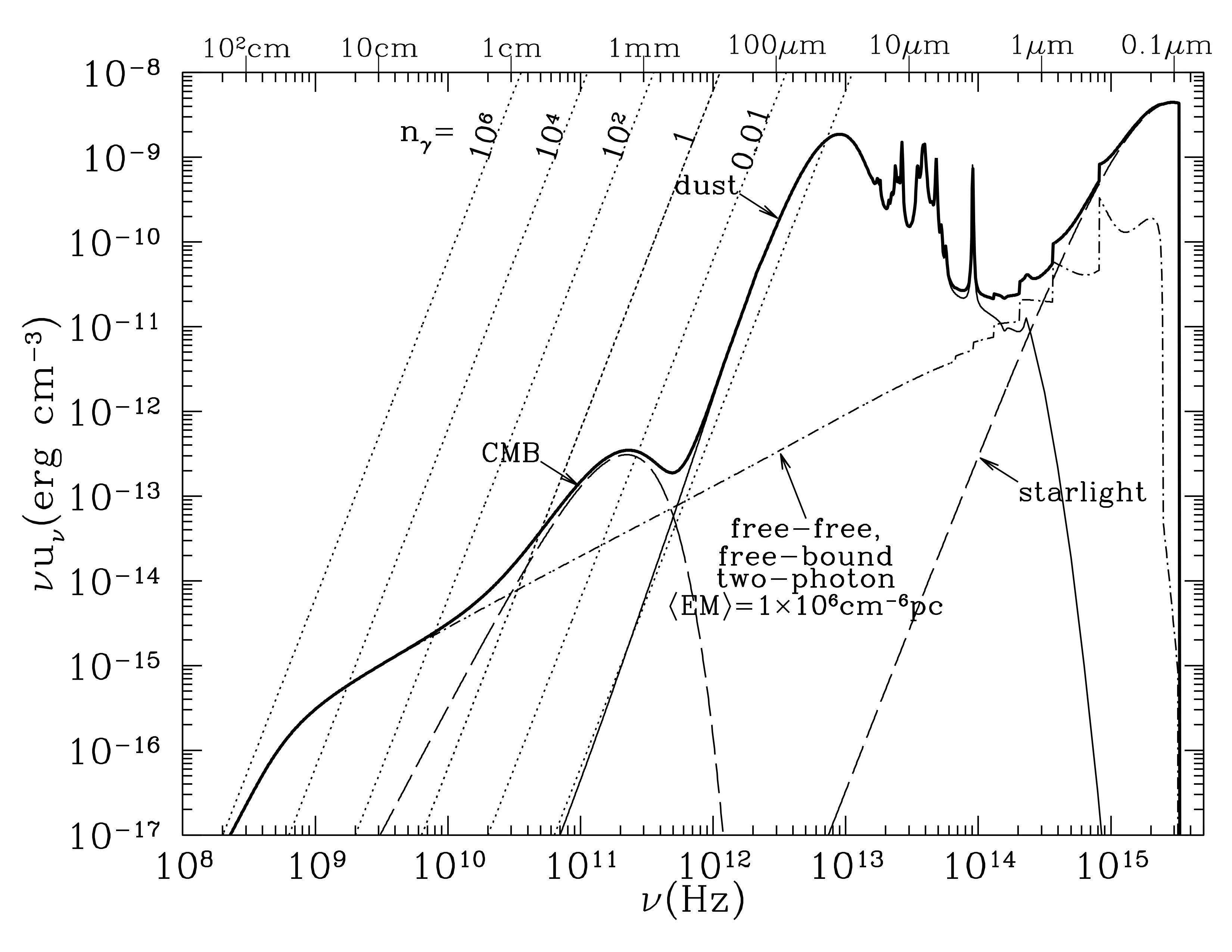

Interstellar continuum radiation field \(u_\nu\) (spectral energy distribution) in an H I cloud in the solar neighborhood (not including spectral lines). Solid line is the sum of all individual components. Squares are additional all-sky measurements from COBE-DIRBE and ROSAT. Credit: Draine Fig 12.1

In our solar neighborhood, from lowest frequency to highest, we are dominated by

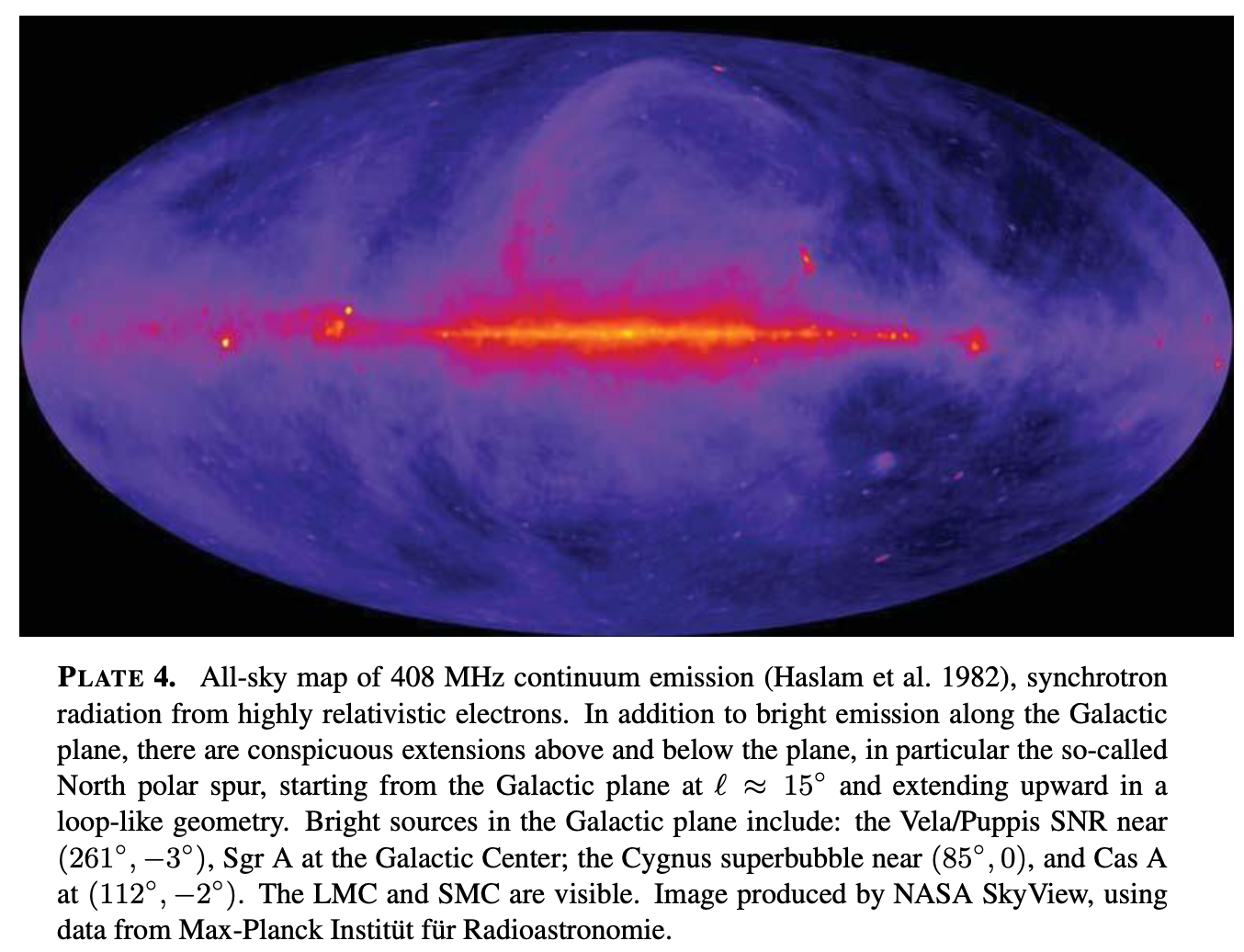

- Galactic synchrotron from relativistic electrons in the galactic magnetic field. Dominates at \(\nu < 1\) GHz. Spatially variable, enhanced near SNe remnants. You can measure the sky-averaged antenna temperature from synchrotron and you’ll find $$ \langle T_A \rangle \approx 700\,\mathrm{K} $$ at \(\nu = 140\) MHz, meaning that the radio sky (at low frequencies) is very bright. But, the total energy density (integrated over relevant frequencies) is comparably small.

Credit: Draine Plate 4

- CMB at \(\nu=1\) GHz, the CMB exceeds the synchrotron. \(T_\mathrm{CMB} = 2.7255\), essentially isotropic, with the primary departure from the dipole perturbation of the motion of the Sun relative to CMB rest-frame.

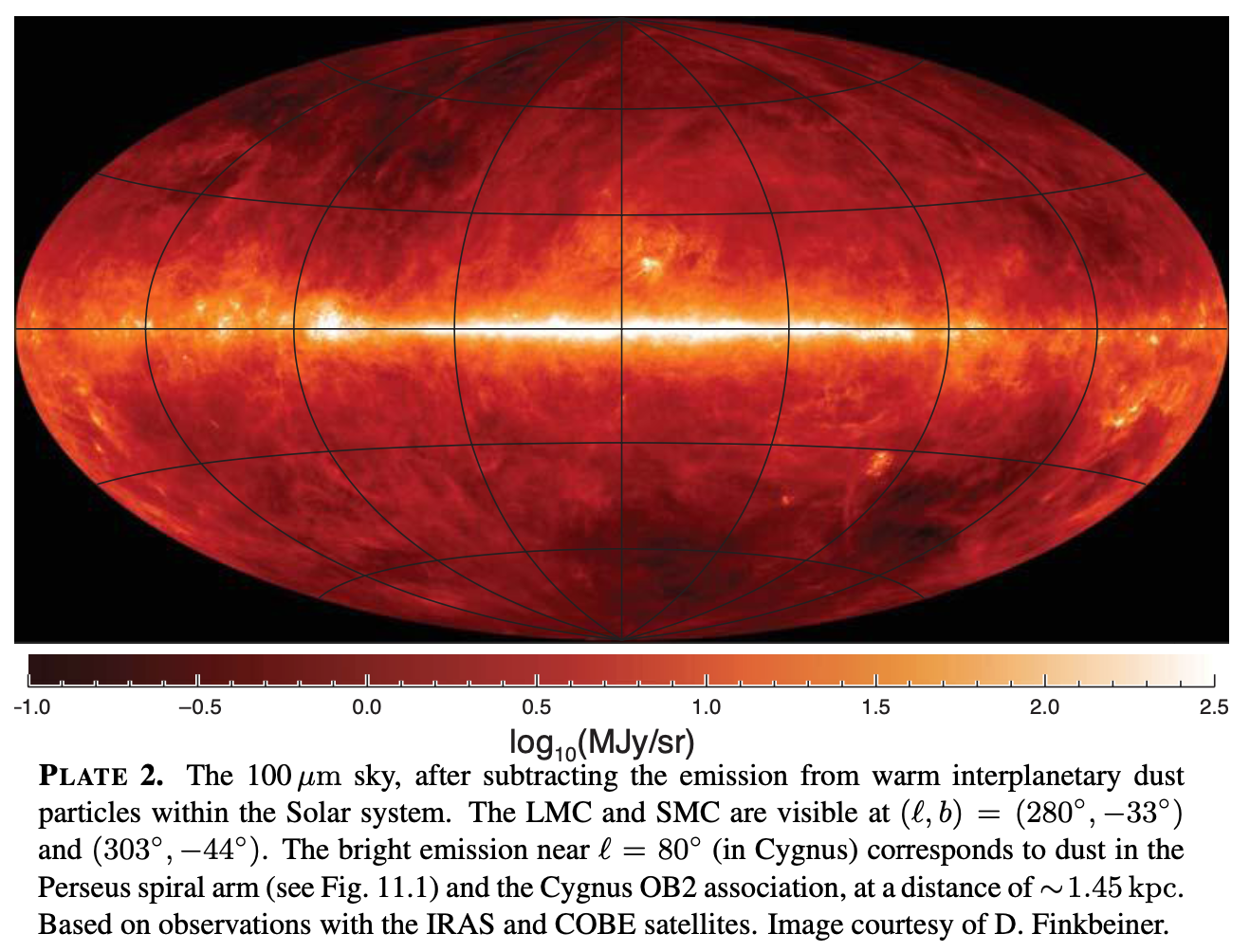

- Far-infrared (FIR) and infrared (IR) emission from dust grains heated by starlight. Dominates between wavelengths of 600 microns up to 5 microns. Most of the spectrum can be approximated as thermal emission from dust grains at a temperature of 17 K. The remaining part is (wavelengths shorter than 50 microns) is power radiated by vibrational emission bands, likely from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) particles

Credit: Draine Plate 2

- Emission from \(10^4\) K plasma, which includes free-free, free-bound, and bound-bound transitions.

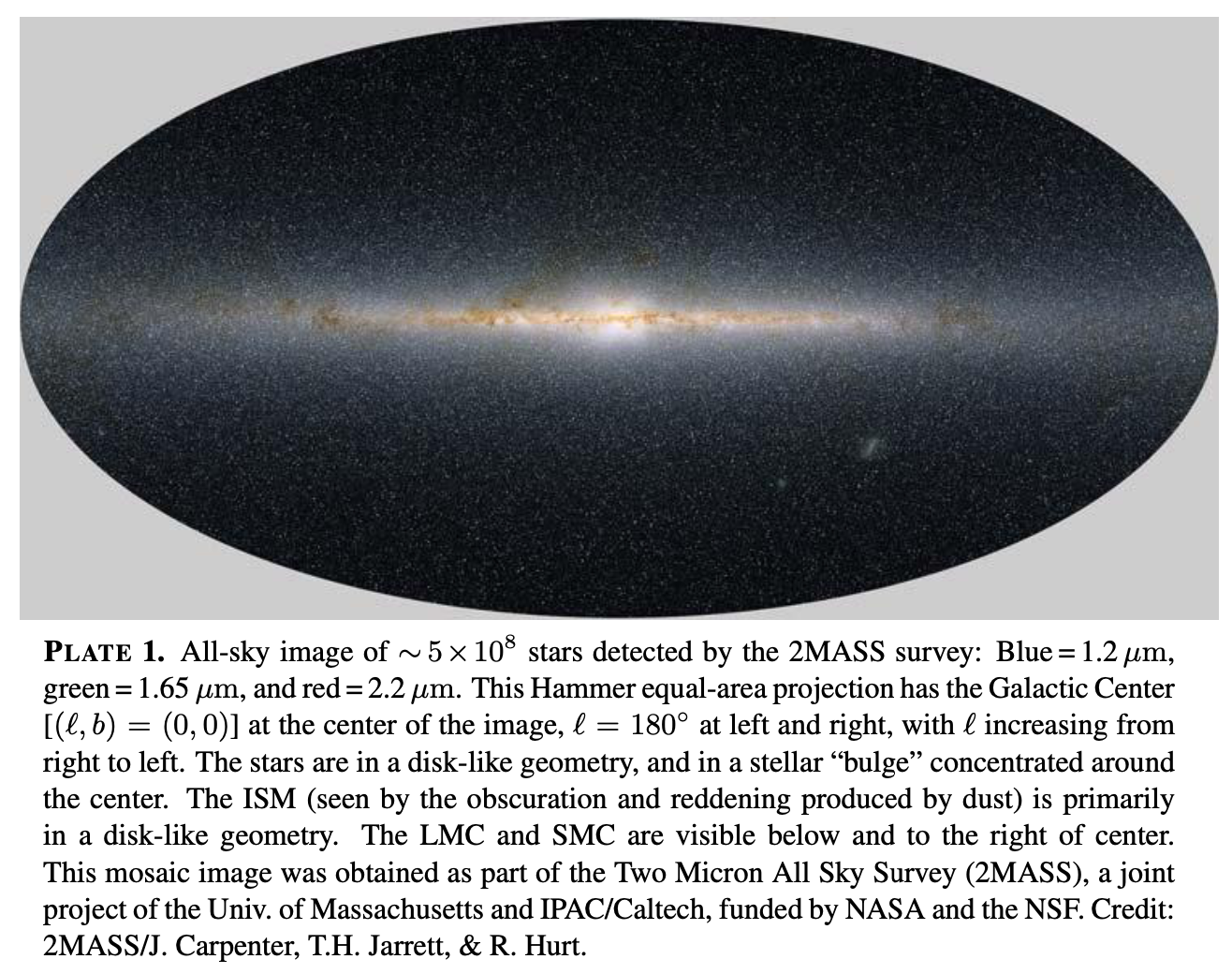

- Starlight, i.e., photons from stellar photospheres. At optical wavelengths, most photons are starlight. Local starlight background is the sum of diffuse blackbodies. Within an H I region, very little radiation at UV and FUV wavelengths (see super shop dropoff), because this radiation is strongly absorbed by neutral H and He. This type of radiation is very important for photoexciting \(\mathrm{H}_2\) and other molecules, photoionizing heavy elements, and ejecting photons from dust grains. The UV radiation is very spatially variable, because the O and B stars that are the primary emitters of this radiation are sporadic and clumped together in star forming regions.

Credit: Draine Plate 1

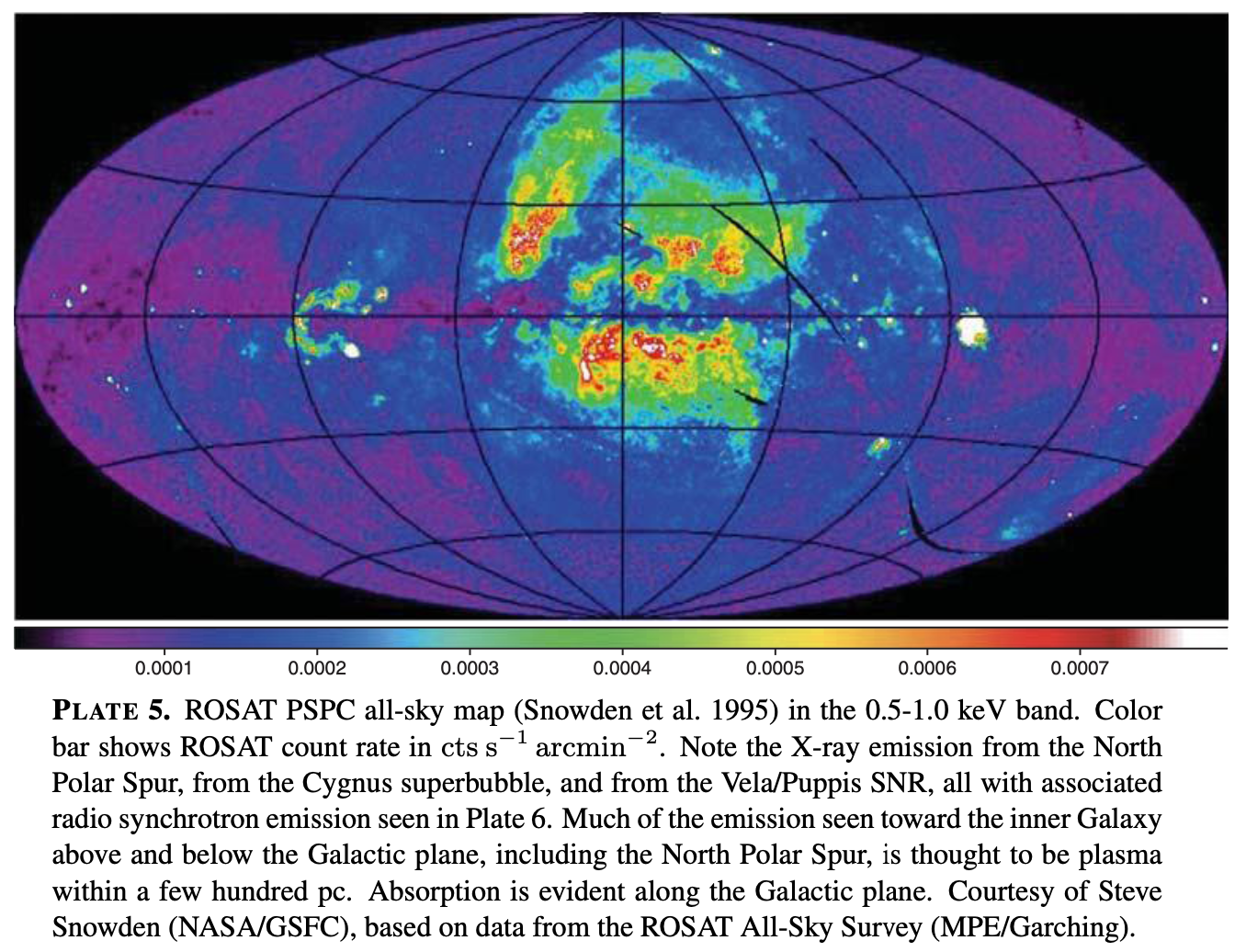

- X-ray emission from very hot (\(T = 10^5 - 10^8\)) K plasma. Most of this from SNe, injecting energy into the ISM, energy goes into thermal plasma, and then re-radiated as x-rays and extreme UV. Lower energies easily absorbed by neutral H I, so at the boundary between this and the starlight regions, the radiation density is highly variable. In external galaxies, AGN can make this part of energy density much higher.

Credit: Draine Plate 5

Spectrum in a photodissociation region (PDR)

Let’s look at a massive O star illuminating an H II region adjacent to a molecular cloud, called a photodissociation region or PDR.

Compared to the previous, this radiation field additionally includes

- radiation from the O star (at \( h \nu < 13.6 )) eV), everything higher absorbed within H II

- free-free emission from H II region

- line emission from H II

- emission from warm dust in PDR

Radiation field in neutral gas adjacent to an H II: region. Starlight from an O star. Spectral lines not shown. Credit: Draine, Figure 12.3

Ionization Processes

- Draine Ch. 13

Ionization state varies widely from place to place. Define ionization fraction $$ x_e = n_e/n_\mathrm{H}. $$

- in dense molecular clouds, material is almost entirely neutral \(x_e \lesssim 10^{-6}\)

- in “H I gas,” the hydrogen in predominately neutral but is partially ionized in the range \(10^{-3} < x_e < 10^{-1}\), mostly by cosmic rays. Elements like carbon are photoionized by starlight.

- in an “H II” region, hydrogen is mostly ionized, helium mostly singly ionized, and oxygen or neon doubly ionized

- in a supernova remnant, elements up through carbon may be fully ionized (i.e., no electrons!) and oxygen and neon may contain electrons only in inner shell

Processes that alter ionization state

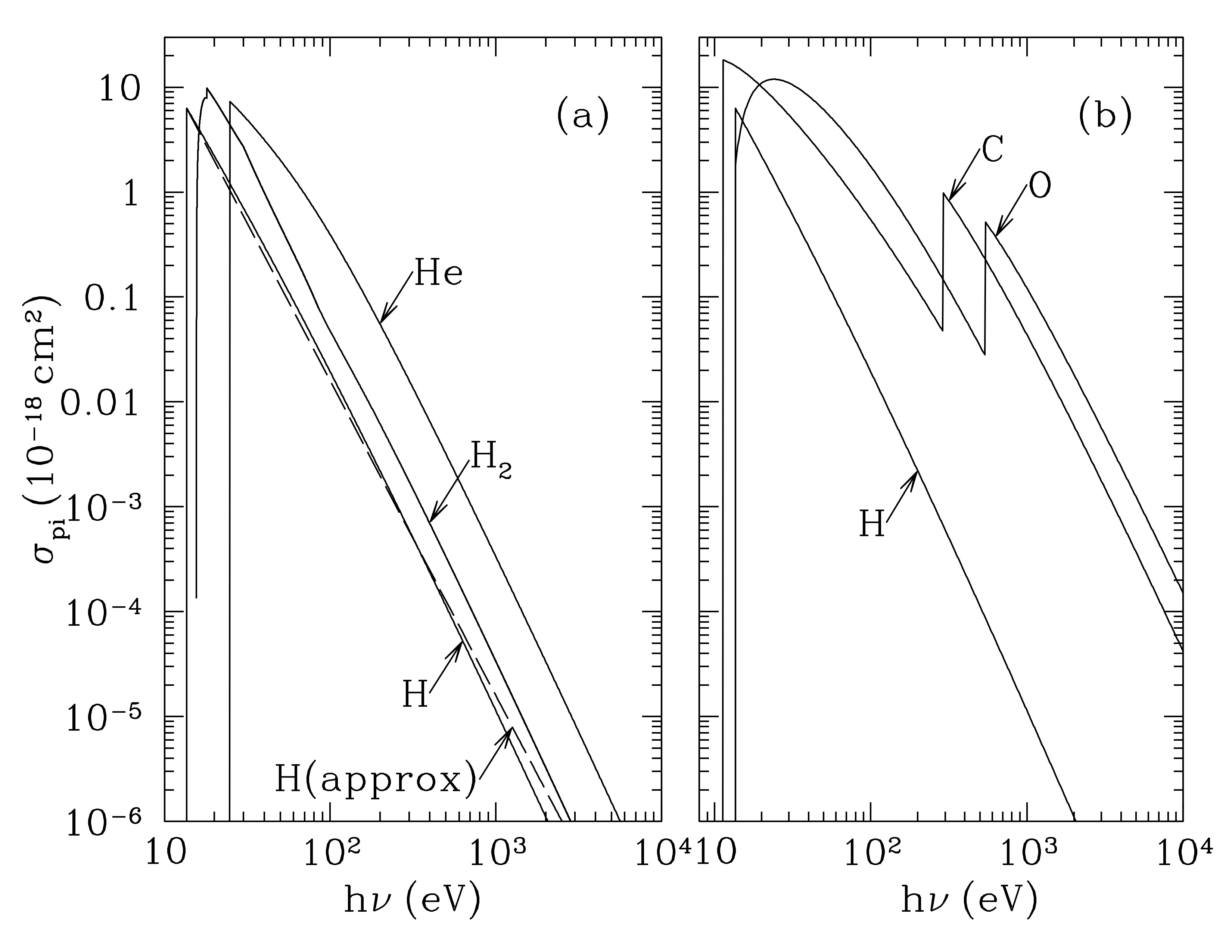

- photoelectric absorption $$ X + h \nu \rightarrow X^+ + e^- $$

Photoionization cross sections for hydrogen atoms, molecular hydrogen, helium, carbon, and oxygen. The cross sections are high when the photon energy is close to the ionization energy, zero when the photon is below this, and decline as a power law when photon energies are much higher. The cross sections for C and O have an absorption edge corresponding to the minimum photon energy for photoionization from the 1s shell, thus boosting the cross section considerably compared to hydrogen. Credit: Draine 13.1

- photoelectric absorption followed by Auger effect: photoionization ejects an electron from inner shell, one electron from outer shell drops, second electron promoted to an excited level, possibly unbound

- collisional ionization $$ X + e^- \rightarrow X^+ + 2 e^- $$ Electron hits an atom, removes another electron, leaving ionized atom.

- cosmic ray ionization $$ X + CR \rightarrow X^+ + e^- + CR $$ What are cosmic rays? They can be thought of as “non-thermal” electrons and ions, i.e., they’re moving much faster than would be expected given the local temperature of the plasma.

- charge exchange $$ X + Y^+ \rightarrow X^+ + Y $$ (see next section)

Recombination of Ions with Electrons

- Draine Ch. 14

This is the inverse of the processes we just discussed.

- radiative recombination

$$

X^+ + e^- \rightarrow X + h \nu

$$

If recombination takes place such that the electron goes straight to the ground state, then the photon that is emitted can ionize hydrogen. If the region has a significant population of neutral hydrogen, then the emitted photon will have a high probability of being absorbed close to where it was emitted. This sets up two “regimes” of recombination,

- Case A: the region is optically thin to ionizing radiation, such that every ionizing photon emitted during the process escapes. Happens in collisionally ionized regions that are very hot (and very low density)

- Case B: the region is optically thick to ionizing radiation, such that ionizing photons emitted are immediately absorbed. The recombinations directly to the ground state do not change the ionization of the gas, only recombinations to states \(n \geq 2\) do. Happens in photoionized nebulae around O and B stars, aka H II regions

The hydrogen recombination emission spectrum can be calculated from the radiative decays from one level to one or more lower levels. Radiative recombination creates neutral atoms with excited levels, which will then (quickly) decay to other lower levels, producing a characteristic line-emission spectrum.

- the ratios of these lines can be measured and used to calculate the temperature of the region

- the total power from the lines can be used to determine total rate of hydrogen recombination

- relative intensities of recombination lines can be used to estimate dust reddening

- dielectronic recombination $$ X^+ + e^- \rightarrow X^{**} \rightarrow X + h \nu $$ important for high temperature plasmas. Ion captures electron and briefly has two electrons in excited states.

- three-body recombination $$ X^+ + e^- + e^- \rightarrow X + e^- $$

- charge exchange $$ X^+ + Y \rightarrow X + Y^+ $$ Any electron is seized during a collision.

- neutralization by grain $$ X^+ + \mathrm{grain} \rightarrow X + \mathrm{grain}^+ $$ Collision with a grain transfers charge, if the ionization potential exceeds the “work function” of the grain.