Photoionized Gas (HII regions)

References

- Ryden and Pogge Ch 4

- Draine Ch 15

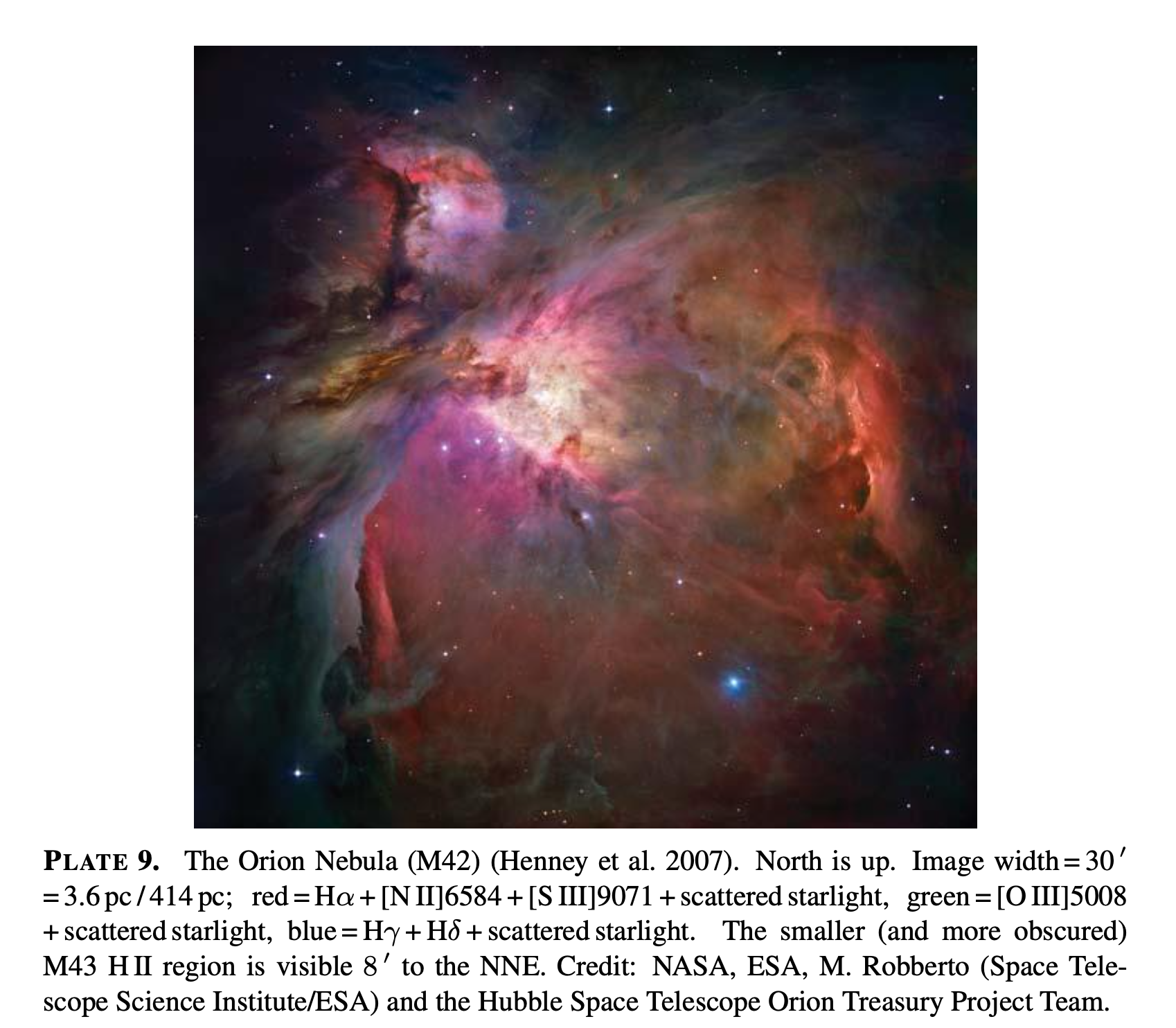

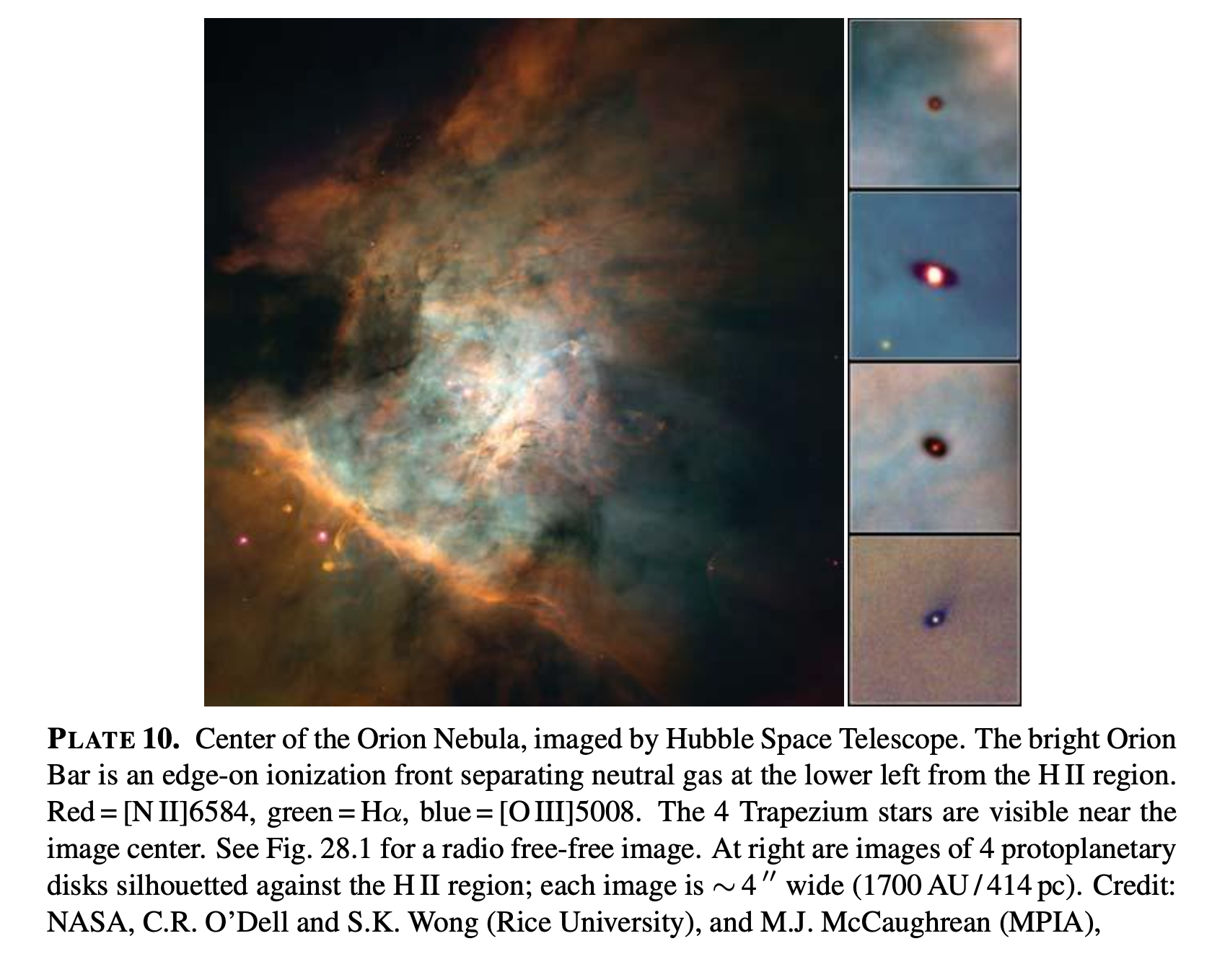

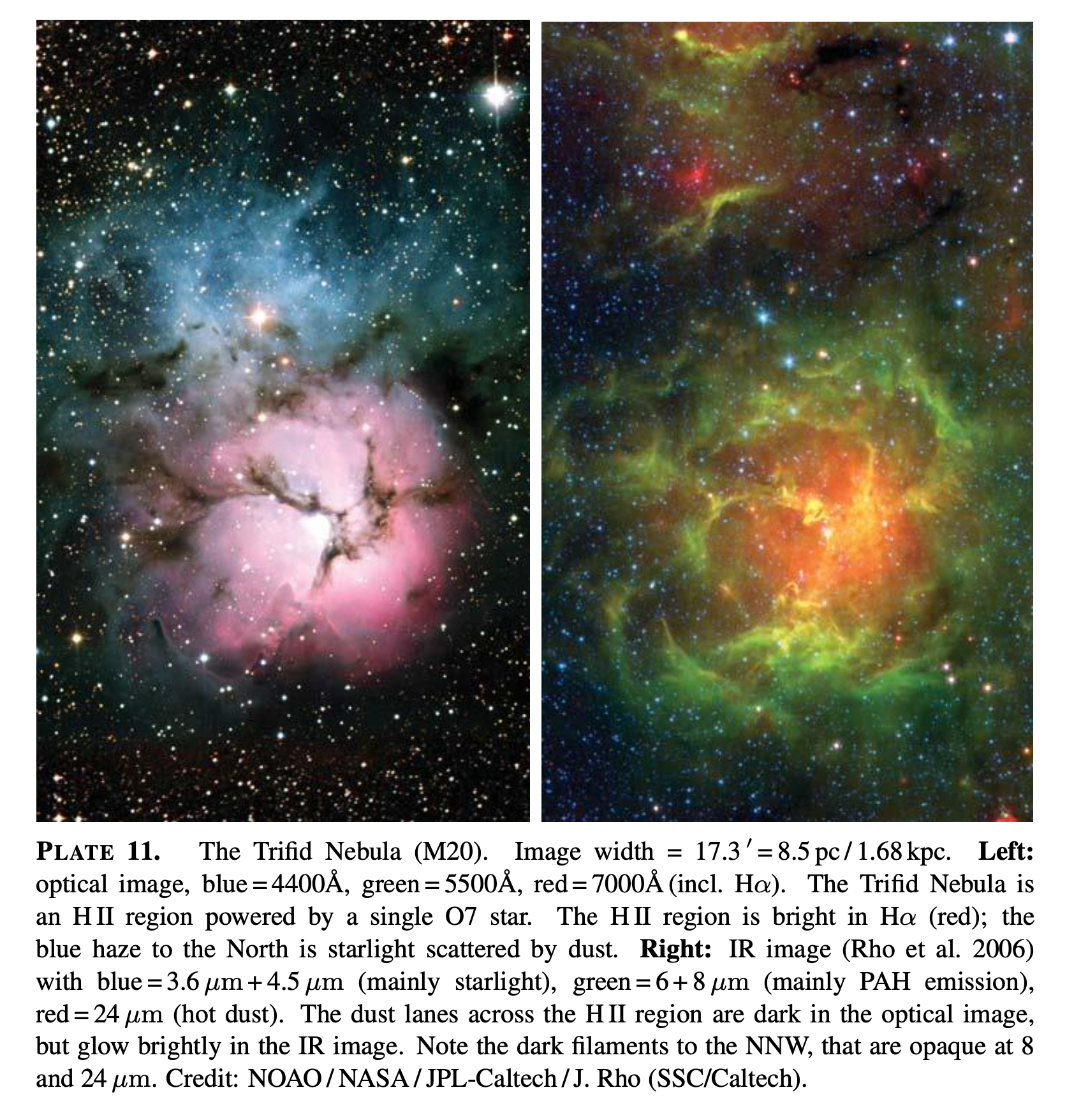

Picture tour

Credit: Draine Plate 9 Credit: Draine Plate 10 Credit: Draine Plate 11

Recall ionization state from previous lecture $$ x_e = \frac{n_e}{n_\mathrm{H}}. $$ Note that here we are using \(n_\mathrm{H}\) as a marker for total number density of hydrogen, not just neutral hydrogen, i.e., \(n_\mathrm{H} = n_{\mathrm{H}^+} + n_{\mathrm{H}^0}\).

In the warm ionized medium \(x_e \sim 0.7\) and in the hot ionized medium \(x_e \sim 1\). Recall from the Saha equation that ionization fraction is a function of temperature.

There is the warm ionized medium (WIM) which is \(T \sim 8000\) K and \( n \approx 0.2\;\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\). There are also H II regions and planetary nebulae (a denser analog to the WIM) that contain many diagnostic tools (in terms of emission) that allow us to determine densities, temperatures, compositions, and ionization states.

first ionization energy: energy required to remove the most loosely bound electron from a neutral atom in its ground state. For hydrogen, this is 13.6 eV, for helium it’s 24.6 eV, for oxygen its 13.6 eV, for carbon its 11.3 eV, see R&P Table 1.2.

question: why do we usually care about the energy required to hydrogen, but don’t talk much about the ionization energy from the \(n=2\) level, which is \(I=3.40\) eV?

answer: in realistic interstellar situations, \(n=2\) rare to find a large population of \(n=2\) hydrogen atoms, and the spontaneous emission \(A_{21}^{-1} \sim 2\) nanoseconds is quick, so rare that we’d have an encounter while it is populated. It would sooner emit a Lyman \(\alpha\) photon. To gain a 50% population of \(n=2\) atoms relative to \(n=1\) in LTE, we’d need to be at about 50,000 K, but at these temperatures the hydrogen will already be pretty much fully ionized.

Photoionization and Radiative Recombination

Photoionization occurs by photoelectric absorption: $$ \mathrm{H} + h \nu \rightarrow p + e^- $$ where the photon energy must be \(h \nu > I_\mathrm{H}\) where \(I_\mathrm{H} = 13.60\) eV (otherwise no ionization will occur).

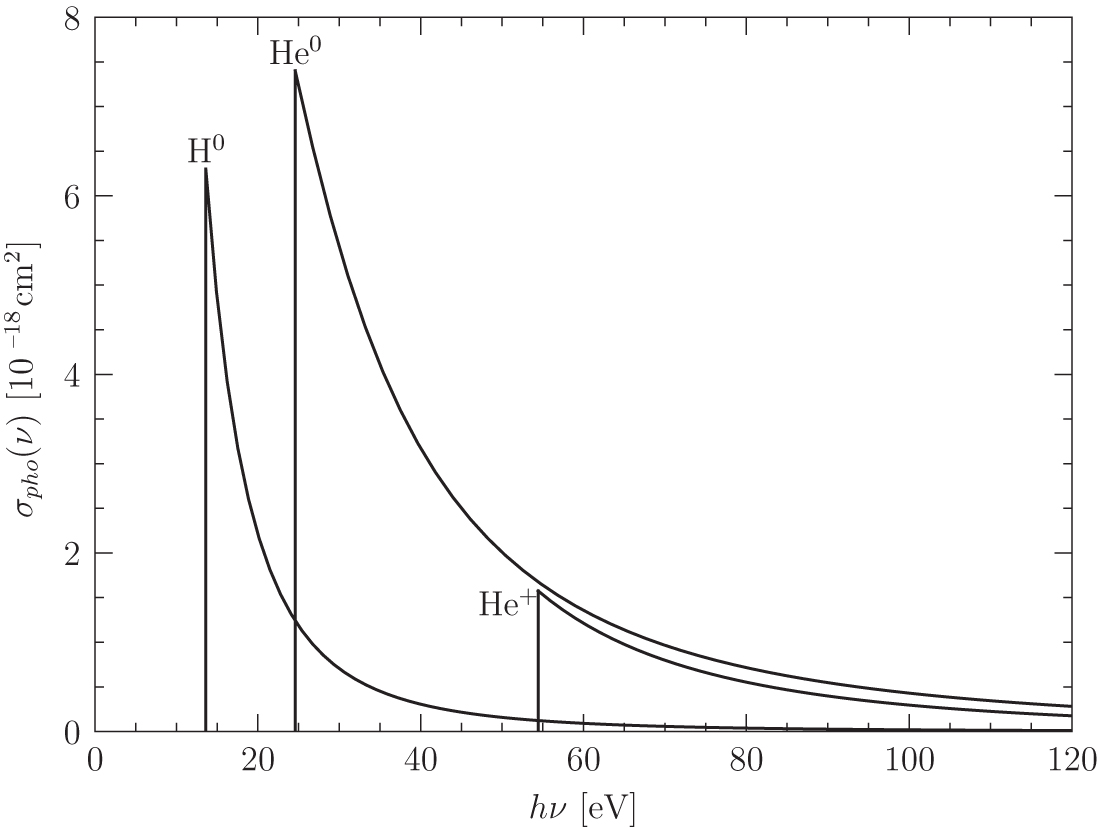

Above this range, we have

$$ \sigma_\mathrm{photo}(\nu) \approx \sigma_0 \left (\frac{h\nu}{Z^2 I_\mathrm{H}} \right)^{-3} $$

Photoionization cross sections for hydrogen, neutral helium, and hydrogenic helium. Credit: Ryden and Pogge, Figure 4.1

Photoionization rate

We can calculate \(\zeta_\mathrm{photo}\) the photoionization rate, or the rate at which a single neutral hydrogen atom undergoes photoionization. $$ \zeta_\mathrm{photo} = \int_{\nu_0}^\infty \frac{\varepsilon_\nu}{h \nu} c \sigma_\mathrm{photo}(\nu)\,d\nu $$ where \(\nu_0\) is the threshold ionization frequency and \(\varepsilon_\nu\) is the background energy density.

Then, the volumetric photoionization rate is $$ \frac{d n_\mathrm{H\,II}}{d t} = n_\mathrm{H\,I} \zeta_\mathrm{photo}. $$

Recombination rate

Radiative recombination is the inverse process to photoionization $$ p + e^- \rightarrow H + h \nu. $$

The radiative recombination rate is \(\alpha\) (we’ve used a more convenient variable than \(\langle \sigma v \rangle\), but its the same idea), and it’s $$ \alpha_{nl}(T) = \left (\frac{8 k T}{\pi m_e} \right)^{1/2} \int_0^\infty \sigma_{rr,nl}(E) \frac{E}{k T} e^{-E/k T} \frac{d E}{k T} $$ and has units of \(\mathrm{cm}^3\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}\).

And the volumetric rate of radiative recombination is $$ \frac{d n_\mathrm{H\,II}}{d t} = - n_e n_\mathrm{H\,II} \alpha. $$

To calculate \(\alpha_n\), you need to sum over all values of angular momentum quantum number \(l\). To calculate \(\alpha\), the total recombination rate, need to sum over principle quantum numbers \(n\).

We can calculate something called the recombination timescale $$ t_\mathrm{rec} \equiv \frac{1}{\alpha n_e} \sim 0.6\;\mathrm{Myr} $$ for H II to undergo radiative recombination. The timescale is typical for the warm ionized medium with \(T=8000\) K and \(n_e \sim 0.1\,\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\).

In ionization equilibrium, we have $$ n_\mathrm{H\,I} \zeta_\mathrm{photo} = n_e n_\mathrm{H\,II} \alpha. $$

Stromgren spheres

“Toy model” of an H II region. Assume we have pure atomic hydrogen gas with uniform density \(n_\mathrm{H}\) that surrounds a central point source of light. What does the ionization fraction look like as a function of radius, as a function of time?

Assume the central light source produces ionizing photons with \(h \nu > I_\mathrm{H}\) at a constant rate \(Q_0\) (i.e., photons/s). For a real O3 star with \(T_\mathrm{eff} \approx 45000\)K, \(Q_0 = 7.6\times10^{47}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}\).

Say we “turn on” the star at \(t=0\), the mean free path for ionizing photons traveling through the neutral medium is $$ \lambda_\mathrm{mfp} = \frac{1}{n_\mathrm{H} \sigma_\mathrm{photo}} = 0.0014\,\mathrm{pc} \left ( \frac{n_\mathrm{H}}{40\,\mathrm{cm}^{-2}} \right)^{-1} \left ( \frac{\sigma_\mathrm{photo}}{6 \times 10^{-18}\,\mathrm{cm}^2} \right )^{-1} $$ scalings are for cold neutral medium and photon just above ionization energy.

Calculate the volume of ionized gas

Assume that every ionizing photon will ionize hydrogen (and just pass through ionized hydrogen), $$ Q_0 = n_\mathrm{H} \frac{d V}{d t} = n_\mathrm{H} 4 \pi R^2 \frac{d R}{d t} $$ which we can integrate and find that the radius increases like $$ R(t) = \left( \frac{3 Q_0}{4 \pi n_\mathrm{H}} t \right)^{1/3}. $$

We have neglected the facts that

- protons and electrons recombine at a rate proportional to \(\alpha n_e n_\mathrm{H\,II}\)

- some UV photons from central source reionize atoms that recombined

which modifies the equation to $$ Q_0 = n_\mathrm{H} 4 \pi R^2 \frac{d R}{d t} + \alpha_{B,H} n_e n_H \frac{4 \pi}{3} R^3 $$ or $$ Q_0 = n_\mathrm{H} 4 \pi R^2 \frac{d R}{d t} + \alpha_{B,H} n_H^2 \frac{4 \pi}{3} R^3 $$ we have assume the ionized sphere to be optically thick to ionizing radiation (case B) an that the fractional ionization is \(x = 1\).

We can integrate this and obtain $$ R(t) = R_S \left (1 - e^{-t/t_\mathrm{rec}} \right)^{1/3} $$ where the Stromgren radius \(R_S\) is $$ R_S \equiv \left (\frac{3 Q_0}{4 \pi \alpha_{B,H} n^2_H} \right)^{1/3} \approx 5.5\,\mathrm{pc}. $$

We can recalculate the recombination time assuming Case B and in a setup where we have a pure hydrogen H II region with fractional ionization \(x \approx 1\). $$ t_\mathrm{rec} \approx \frac{1}{\alpha_{B, H} n_H} \approx 2600\,\mathrm{yr} $$

So it takes about 3000 years to create a Stromgren sphere.

At times \(t \gg t_\mathrm{rec}\), the Stromgren sphere will consist of a sphere of almost fully ionized gas with radius \(R \rightarrow R_S \sim 6\,\mathrm{pc}\). Outside of this, there will be a partially ionized boundary of thickness \(\lambda_\mathrm{mfp} \sim 0.001\,\mathrm{pc} \ll R_S\), and outside of this, neutral hydrogen.

Because radiative recombination is the reversal of photoionization, \(t_\mathrm{rec}\) is also the time it takes for the sphere to go back to neutral H after the central UV source has been turned off.

The Stromgren sphere approaches ionization temperature, but it’s still far from pressure equilibrium, and as it’s heated, it will begin to expand.