Ionization in Predominantly Neutral Regions (cool + warm HI regions)

- Draine Ch. 16

What is the degree of ionization expected in predominately neutral interstellar clouds?

- \(n_e\) determines ionization balance of various species

- collisions with free electrons play a role in determining the charge state for interstellar grains

- electrons play a role in interstellar chemistry and sometimes cool the gas via collisional excitation

Three main regimes to consider

- diffuse H I regions: metals are photoionized by starlight; cosmic rays create a small amount of \(\mathrm{H}^+\) and \(\mathrm{He}^+\). The gas may be CNM or WNM.

- diffuse molecular clouds: (e.g., moderate visual extinction \(0.3 \lesssim A_V \lesssim 2\,\mathrm{mag}\)). Most hydrogen is in \(H_\mathrm{2}\), metals still predominately photoionized by starlight. Cosmic rays can produce \(H_2^+\), which leads to the formation of \(H_3^+\).

- dark molecular clouds: (e.g., visual extinction \(A_V \gtrsim 3\,\mathrm{mag}\)). Insufficient UV radiation to photoionize elements like C and S. CRs can maintain only a very small ionization \(10^{-7}\).

Ionization of metals in H I regions

Carbon is the fourth most astrophysically abundant element.

- Q: what’s the third?

- A: oxygen

Nearly 60% of the carbon in the ISM is in solid grains, leaving a gas phase abundance of \(n_C / n_H \approx 1 \times 10^{-4}\).

As we talked about in previous lectures, stellar photons with energies greater than \(I_H = 13.6\) eV cannot penetrate appreciable quantities of H I gas because the cross-section for photoionization is large. But, carbon has an ionization energy of 11.26 eV, which means that it can be ionized by starlight photons that will penetrate H I. As a result, under typical ISM conditions, we find that 99% of the carbon is ionized.

Ionization of hydrogen in cool H I regions

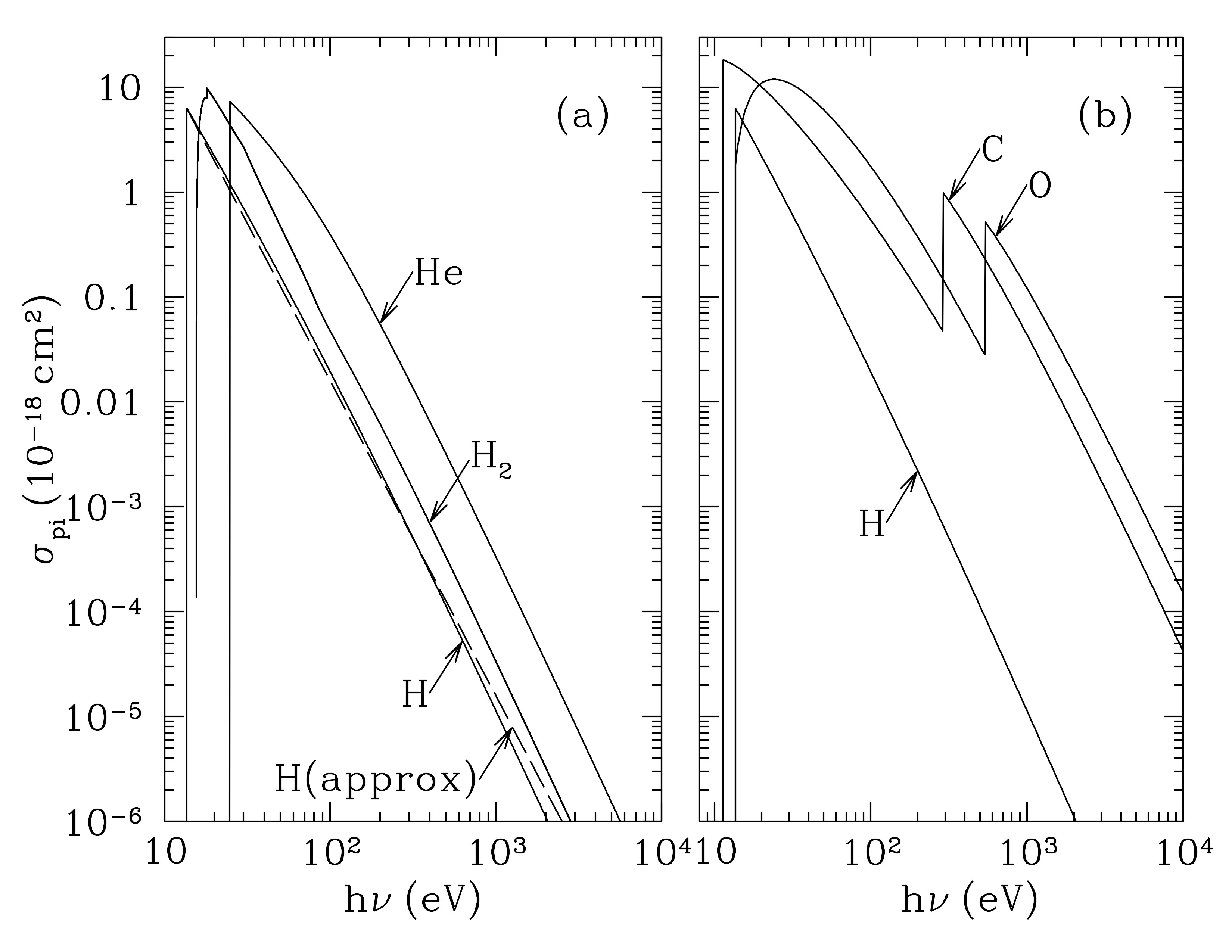

Stellar photons with energies greater than \(I_H = 13.6\) eV cannot penetrate appreciable quantities of H I gas, however x-rays of sufficiently high energies can reach the interior of clouds. Let’s revisit the photoionization cross sections from Ch. 13 to see why this is the case:

Photoionization cross sections for hydrogen atoms, molecular hydrogen, helium, carbon, and oxygen. The cross sections are high when the photon energy is close to the ionization energy, zero when the photon is below this, and decline as a power law when photon energies are much higher. The cross sections for C and O have an absorption edge corresponding to the minimum photon energy for photoionization from the 1s shell, thus boosting the cross section considerably compared to hydrogen. Credit: Draine 13.1

Still, we’re talking about ionization fractions of \(n_e \lesssim 0.01\,\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\).

Also need to consider cosmic ray flux.

Diffuse molecular gas

\(0.3 \lesssim A_V \lesssim 2\,\mathrm{mag}\)

In regions where molecular hydrogen can be found, most ionizations produced by cosmic rays or x rays

- detach an electron from \(H_\mathrm{2}\) to create \(\mathrm{H}^+\)

- if it encounters an electron, the \(\mathrm{H}^+\) will dissociatively recombine $$ \mathrm{H}_2^+ + e^- \rightarrow \mathrm{H} + \mathrm{H} $$

But, since the electron fraction in molecular gas is low, it may not encounter an electron before it undergoes the fast exothermic ion-molecular reaction $$ \mathrm{H}_2^+ + \mathrm{H}_2 \rightarrow \mathrm{H}_3^+ + \mathrm{H} $$ to form \(\mathrm{H}_3^+\), which will eventually dissociatively recombine.

Because all of these involve free electron densities, we can use the ratio of $$ \frac{N(\mathrm{H}_3^+)}{N(\mathrm{H}_2^+)} $$ to estimate the cosmic ray ionization rate in molecular clouds.

Dense Molecular Clouds (dark clouds)

When \(A_V \gtrsim 3\,\mathrm{mag}\), even carbon and sulfur remain predominately neutral. Most of the free electrons come from cosmic ray ionization.

As before, CR ionization produces \(\mathrm{H}_2^+\), which leads to \(\mathrm{H}_3^+\). However, in dense molecular clouds the ionization fraction is so low that most of these \(\mathrm{H}_3^+\) ions react with atoms or molecules (like CO) to form a generic molecule (like \(HCO^+\)), which will then recombine dissociatively, capture an electron from a grain, or charge exchange with a neutral atom like sulfur.

The end result of these reactions, though, is that deep within a molecular cloud cosmic ray ionization is the only source of free electrons, and even then, the gas has a very low ionization fraction. This has bearing on the magnetohydrodynamics of the gas, because ionized gas interacts with a magnetic field, while neutral gas doesn’t.