Interstellar Dust

References

- Ryden and Pogge Ch 6.1

- Draine Ch. 21

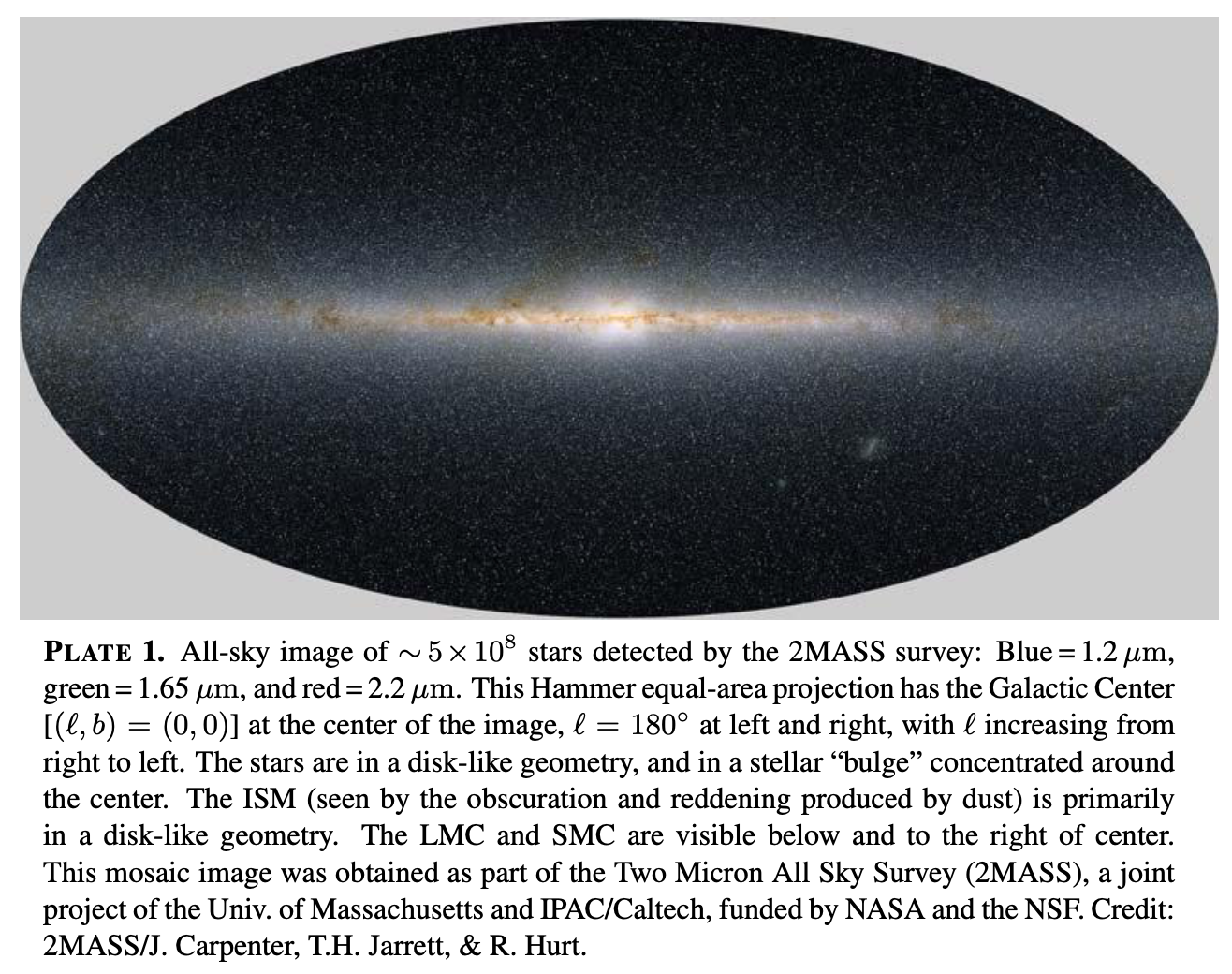

Modern astronomers are quick to recognize the effects of dust obscuration, such as in the dark lanes across the Milky Way Galaxy

Credit: Draine Plate 1

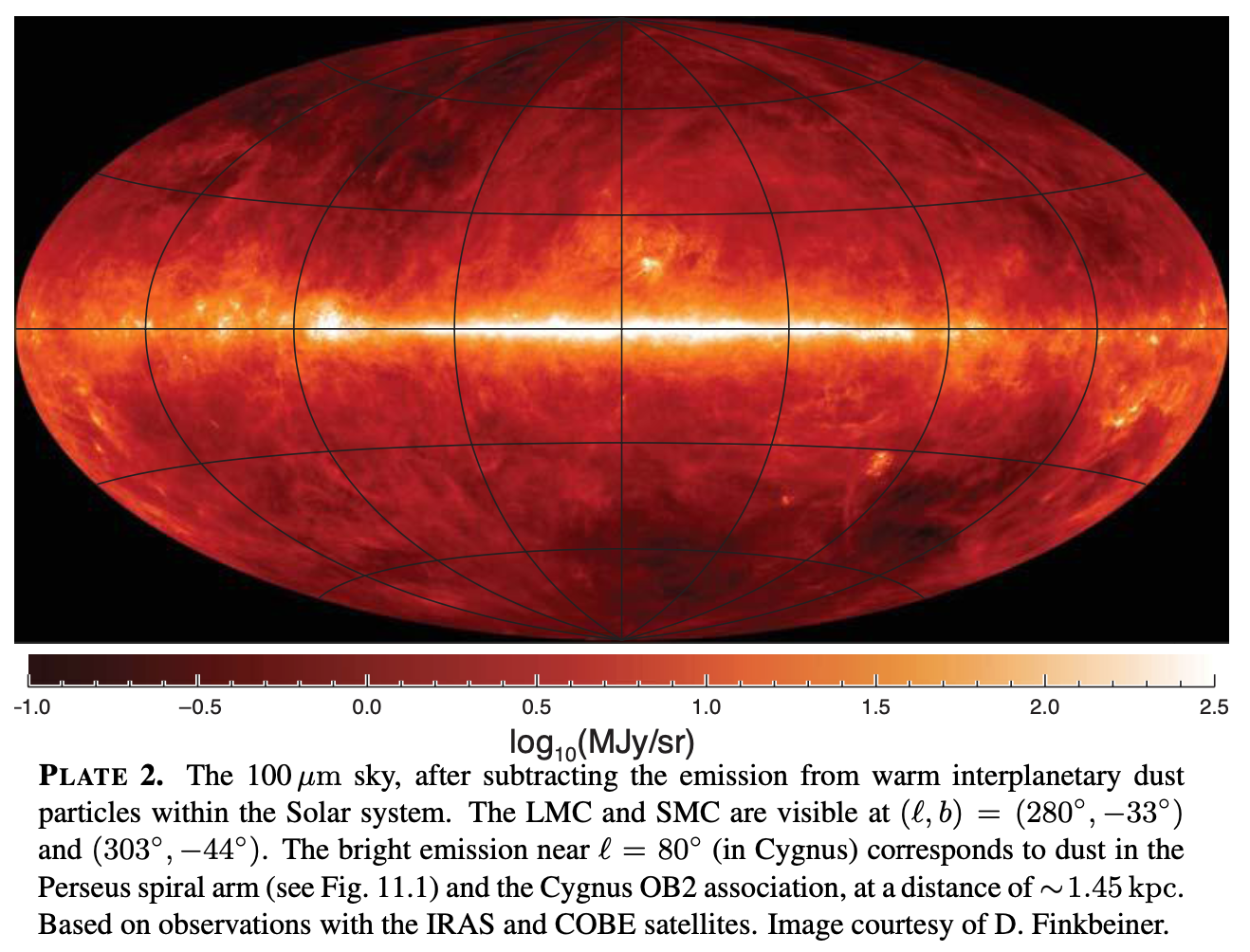

And of course we can use infrared observations to directly measure the emission from dust

Credit: Draine Plate 2

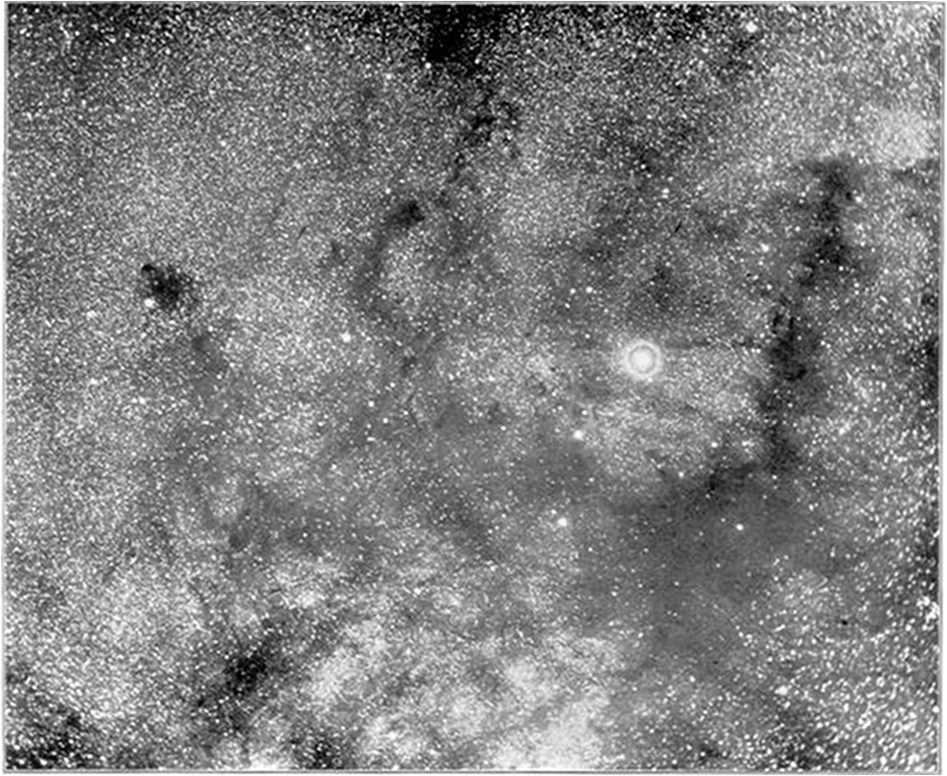

But without these tools, how could you be so sure that something like dust must exist, especially just by observing by eye? Astrophotographs by Barnard in the late 1800s and early 1900s were highly suggestive of dark or obscuring structures.

Photograph by E.E. Barnard of the dark structures near the Theta Ophiuchi (bright star w/ diffraction ring) Credit: Ryden and Pogge, Figure 6.1. Originally Barnard 1899

The widespread existence of dust came about in the work by Robert Trumpler in 1930, when he studied open clusters in our Galaxy. Basically, he treated bright main sequence stars as standard candles, the size of clusters as standard rulers, and found that things didn’t correlate the way he might expect just from the inverse square law alone. Instead, he found a better fit if the light was attenuated exponentially $$ I_\lambda = I_{\lambda, 0} e^{-\kappa_\lambda r} $$ with a wavelength dependence such that bluer wavelengths suffered larger attenuation.

Dust

- dims light (overall)

- dims blue optical wavelengths more than red optical or infrared wavelengths

Trumpler hypothesized that this could be due to Rayleigh scattering from “fine cosmic dust particles.”

Effect of dust on observations

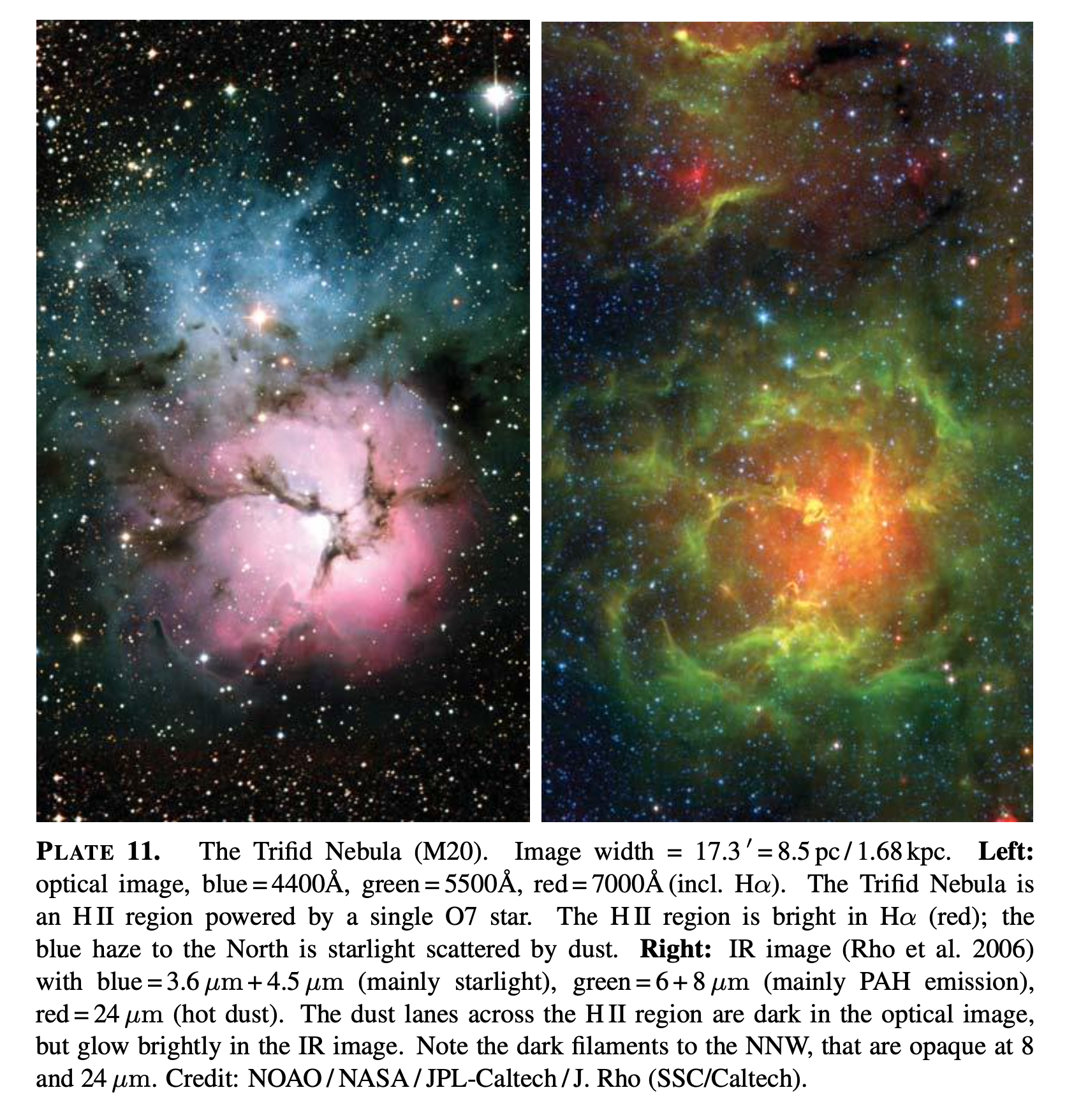

- Dust particles scatter light. We see this in reflection nebulae.

- Dust particles also absorb light.

The blue nebulosity in the north is primarily scattered light. Credit: Draine Plate 11

The net effect of scattering and absorption is called extinction. Extinction can depend on the polarization of the light, and so dust can also polarize light.

The relative amount of scattering and absorbing depends on the properties of the dust grains.

We can write the observed flux of a star as $$ F_\lambda = F_{\lambda, 0} e^{-\tau_\lambda} $$ basically, the original flux attenuated by a medium with some optical depth.

There isn’t much starlight at energies \(h \nu > 13.6\) eV, so dust extinction studies have generally focused on near UV and optical \(\lambda > 912\) angstroms.

Because optical astronomers are usually making these calculations, we’re usually working in magnitudes. So, we can write the ratio of the original flux to the attenuated flux relative as a number of magnitudes of extinction. The definition is

$$ A_\lambda = 2.5 \log_{10} \left ( \frac{F_{\lambda, 0}}{F_\lambda } \right) $$ making the relationship between magnitudes and optical depth $$ A_\lambda = 2.5 \log_{10}(e^{\tau_\nu}) \approx 1.086 \tau_\lambda. $$

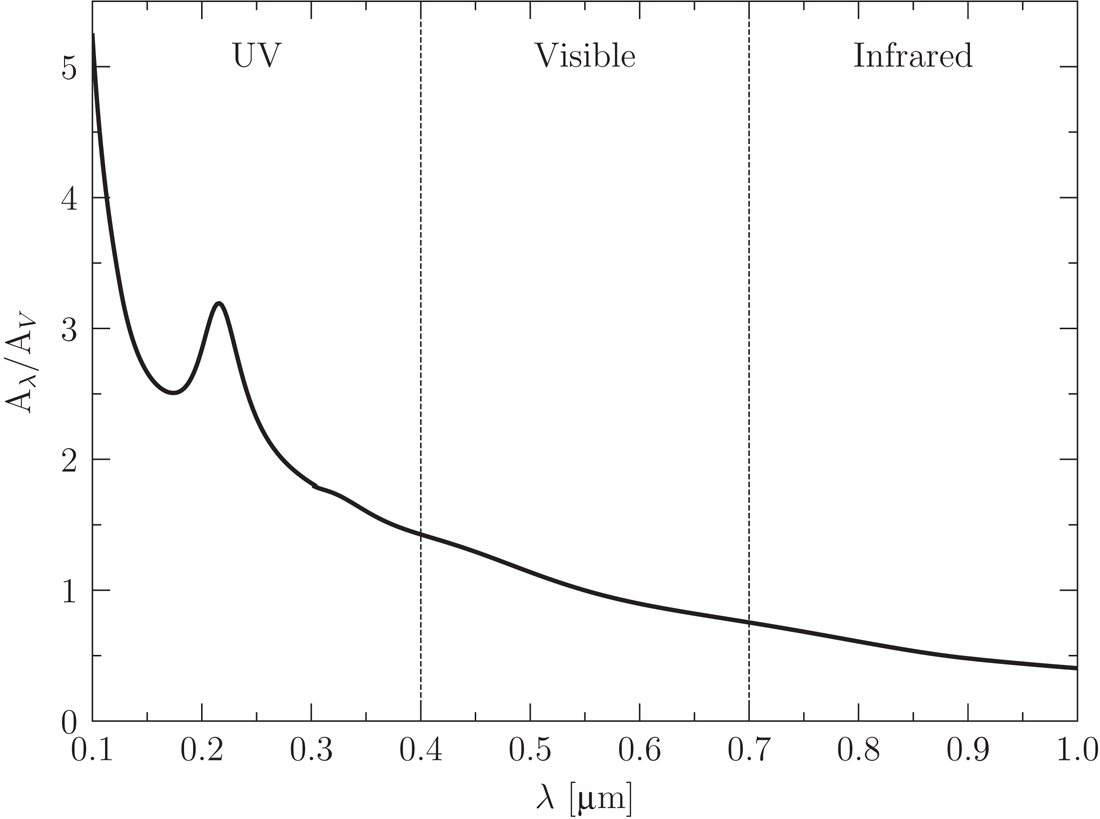

The exctinction curve as a function of wavelength looks like the following

Dust exctinction as a function of wavelength, normalized relative to \(A_V\), the extinction in the V band. Credit: Ryden and Pogge, Figure 6.2. data from Cardelli+94 and O’Donnell 94.

and this is determined by comparing the spectrum of a nearby (un-extincted) star to a more distant star of the same spectral type.

Cardelli+89 showed that the extinction relative to some reference wavelength can be described as a function $$ A_\lambda / A_{\lambda_\mathrm{ref}} \approx f(\lambda) $$

The actual functional form is a non-parametric spline fit with seven free parameters.

The first thing you should notice is that bluer wavelengths (in particular UV and blue optical) are much more heavily extincted than redder wavelengths (red optical and near-infrared). This means that dust will attenuate and redden the light from a star.

There is also an excess extinction feature at \(\lambda \approx 2175\) angstroms, which is attributed to carbon rich particles. It is metallicity dependent.

At optical wavelengths, the extinction is a bit simpler. At optical and near-UV wavelengths, the functional form can be approximated by a one-parameter family of curves $$ A_\lambda / A_{\lambda_\mathrm{ref}} \approx f(\lambda; R_V) $$ where that one parameter is \(R_V\).

The redenning is commonly expressed in terms of a color excess between B and V optical bands, $$ E(B-V) = A_B - A_V $$ and is usually a positive number.

If you assume that the extinction curve is the same everywhere, then by knowing \(A_V\) you would be able to calculate \(E(B-V)\) (or vice-versa). Unfortunately it’s not guaranteed to be the same everywhere, and in fact, the ratio of total to selective extinction is $$ R_V \equiv \frac{A_V}{E(B-V)} $$ and ranges for values of \(2 \lesssim R_V \lesssim 6\) for interstellar dust, which means that for every magnitude of \(V\)-band extinction, you’re going to get 1.2 - 1.5 magnitudes of B band extinction. You can think of \(R_V\) as the inverse of the slope of the extinction curve at optical wavelengths.

If \(R_V \rightarrow \infty\), then you have a “grey” absorber where all wavelengths of light are absorbed equally. This would also be what happens if we were in the “geometric optics” limit, where the dust grains were large compared to the wavelength. The fact that we do see extinction rise with wavelength means that small grains (\(a \lesssim 0.015\,\mu m\)) must be making an appreciable contribution to extinction at observed wavelengths.

The most commonly adopted value is \(R_V = 3.1\) for general ISM.

With the Milky Way Galaxy, the amount of dust extinction along a line of sight is found to be correlated with the total column density of hydrogen.

For sightlines with \(R_V \approx 3.1\), $$ \frac{N_H}{A_V} \approx 1.9 \times 10^{21}\,\mathrm{cm}^{-2}\;\mathrm{mag}^{-1}. $$ This is a really useful relationship because if you’ve measured the exctinction, then you can estimate the column density of hydrogen, or vice-versa.

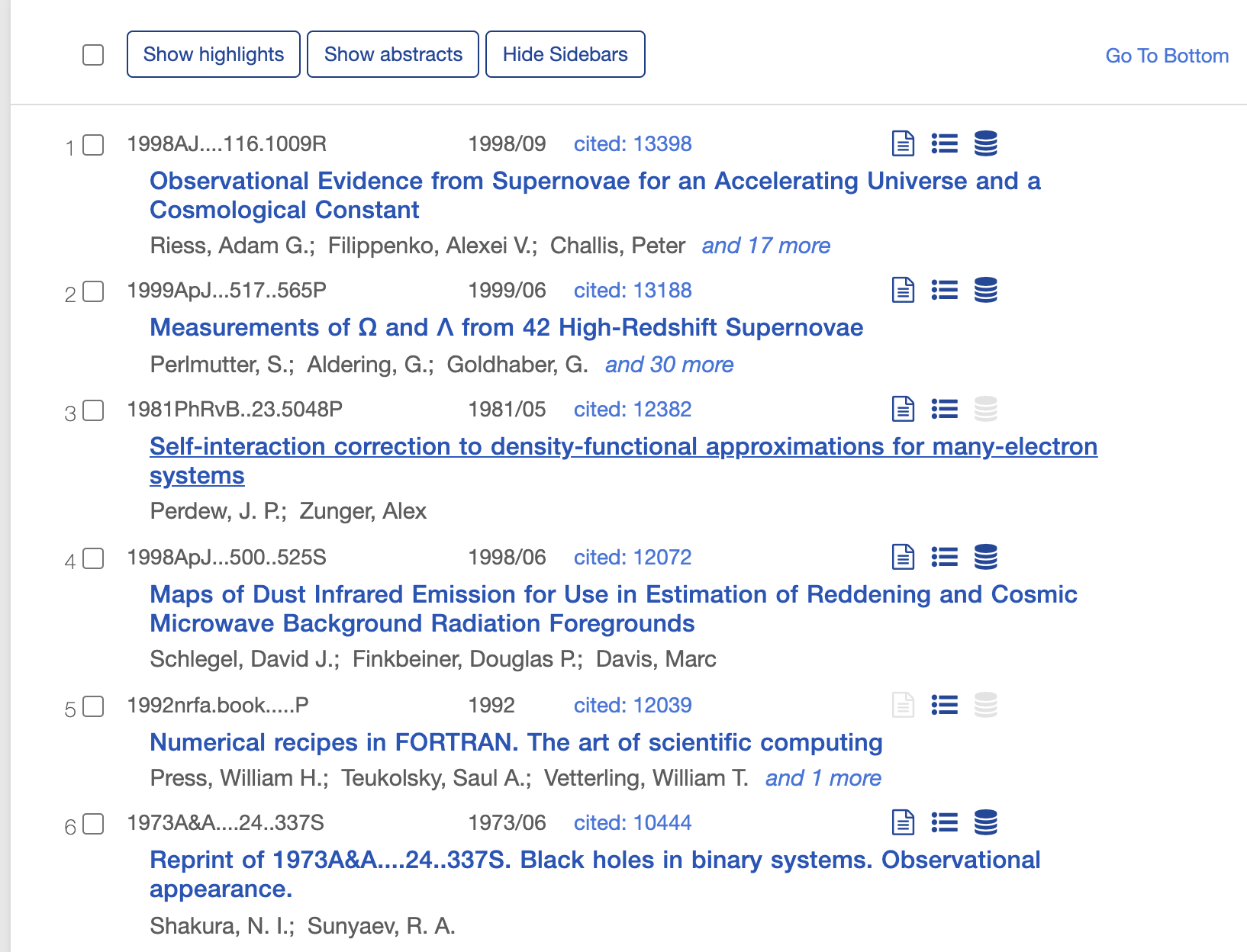

And realistically, you’d try to combine as much information that you can in our galaxy, including dust emission, and then you can produce a map of extinction for any extragalactic source. The most famous of these papers is the “SFD” paper by Schlegel, Finkbeiner, and Davis. Even at high galactic latitudes, there can still be some extinction (~0.05 mags \(A_V\))

A ranking of the most highly cited astronomy papers (retrieved 10/2/2021). Note Schlegel, Finkbeiner, and Davis in 3rd place after the Riess+ and Perlmutter+ papers discovering the accelerating universe. (not sure I would classify the Perdew and Zunger paper as astronomy, despite what ADS says.)

Because some exctinction is caused by absorption instead of scattering, dust grains are heated by (optical) starlight, after which they then cool by the emission of infrared light.

In our Milky Way Galaxy, the infrared portion of the interstellar radiation field peaks at \(\lambda \approx 140\,\mu m\), which corresponds to dust temperatures of 100 K.

Using the hydrogen column density on a typical sightline through our galaxy, we can make an order of magnitude calculation as to the infrared luminosity per hydrogen nucleus $$ \frac{I_\mathrm{IR}}{N_H} = 5 \times 10^{-24}\,\mathrm{erg\,s}^{-1}. $$

By comparision, the Sun’s luminosity per hydrogen nucleus is $$ \sim L_\odot m_H / M_\odot \approx 3 \times 10^{-24}\,\mathrm{erg\,s}^{-1}. $$

So we took a lot of liberty here in the approximations, but the ISM is about as efficient as converting sunlight into infrared light as the Sun is at creating sunlight to begin with. This has important implications for the observations of external galaxies—for some with large dust content, the amount of energy in IR radiation is comparable to that contained in optical starlight.

Basically, the dust in a galaxy is efficient at absorbing optical starlight and re-radiating it as infrared emission.