Scattering and Absorption by Small Particles

References

- Draine Ch. 22

- Ryden and Pogge Ch. 6.2

Cross sections and efficiency factors

In analogy to our previous setups with scattering cross sections, which we wrote as \(\sigma\), we’ll define other cross sections that are useful for talking about grains and radiative transfer. At least in this chapter, Draine labels them by \(C\), and many of them have a dependence on wavelength. They still have units of area, \(\mathrm{cm}^2\).

- absorption cross section \(C_\mathrm{abs}(\lambda)\)

- scattering cross section \(C_\mathrm{sca}(\lambda)\)

- extinction cross section $$ C_\mathrm{ext}(\lambda) = C_\mathrm{abs}(\lambda) + C_\mathrm{sca}(\lambda) $$

A brief note about radiative transfer with scattering included

For a population of identical dust grains with number density \(n\), the extinction cross section is related to the attenuation coefficient by the relation $$ \kappa_\lambda = n C_\mathrm{ext}(\lambda). $$

If you remember back to our radiative transfer lecture, we neglected scattering in nearly all applications. Now, we’re including scattering for dust, and that means that radiative transfer gets hard. We can still calculate the optical depth $$ \tau_\nu = \int_0^s \kappa_\lambda d s, $$ however, to calculate an emergent intensity we can’t just plug it into the integral form of the RTE like we did before. \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{n}\) are vectors. Here is an example including the sink and source terms due to scattering.

The sink term is added simply by using \(\kappa_\mathrm{ext}\), which includes the attenuation due to scattering. The problem starts to get gnarly when we consider the source term due to scattering. Basically, light can be scattered into the ray under consideration (attenuating the ray from which it originated). The modified RTE looks like

$$ \frac{d I}{d s}(x, n, \lambda) = - \kappa_\mathrm{ext}(x, \lambda) I(x, n, \lambda) + j_*(x, n, \lambda) + \kappa_\mathrm{sca}(x, \lambda) \int_{4 \pi} \Phi(n, n^\prime, x, \lambda) I(x, n^\prime, \lambda) d \Omega^\prime $$

where \(\Phi\) term is a scattering phase function, which describes the probability that a photon originally propagating in direction \(\boldsymbol{n}^\prime\) and scattered at position \(\boldsymbol{x}\) will have \(\boldsymbol{n}\) as its new propagation direction.

This is called an integro-differential equation. It sounds hard because it is, and all radiation fields in all positions in all directions (and for all wavelengths) are coupled! For more information on the complexities of radiative transfer including dust, see the review article Steinacker ARA&A.

Back to terms

The albedo $$ \omega \equiv \frac{C_\mathrm{sca}(\lambda)}{C_\mathrm{abs}(\lambda) + C_\mathrm{sca}(\lambda)} = \frac{C_\mathrm{sca}(\lambda)}{C_\mathrm{ext}(\lambda)}. $$ An albedo of 1 means that scattering dominates the extinction (shiny silver thing), an albedo of 0 means that absorption dominates (pure black).

For a given direction of incidence to a fixed grain, you need two angles \(\theta, \phi\) to fully specify the scattering direction, since it can be in any direction in 3D space. However, if we are talking about spherical grains, or a large ensemble of randomly oriented grains, then we only need to talk about a single scattering angle \(\theta\). A value of 0 means that the light is scattered in the forward direction, a value of 180 means that the light is scattered backwards (back-scattered), and a value of 90 would have the light be scattered to the right, left, top, or bottom.

We can write down a differential scattering cross section $$ \frac{d C_\mathrm{sca}(\theta)}{d \Omega} $$ for incident unpolarized light to be scattered by an angle \(\theta\).

We can calculate the mean value of \(\cos \theta\) (scattering angle) by taking the average over all angles $$ \langle \cos \theta \rangle = \frac{1}{C_\mathrm{sca}} \int_0^\pi \cos \theta \frac{d C_\mathrm{sca}(\theta)}{d \Omega} 2 \pi \sin \theta d \theta $$

We can calculate the radiation pressure cross section $$ C_\mathrm{pr}(\lambda) \equiv C_\mathrm{abs}(\lambda) + (1 - \langle \cos \theta \rangle C_\mathrm{sca}(\lambda)). $$

And we also have the degree of polarization for light scattered through an angle \(P(\theta)\).

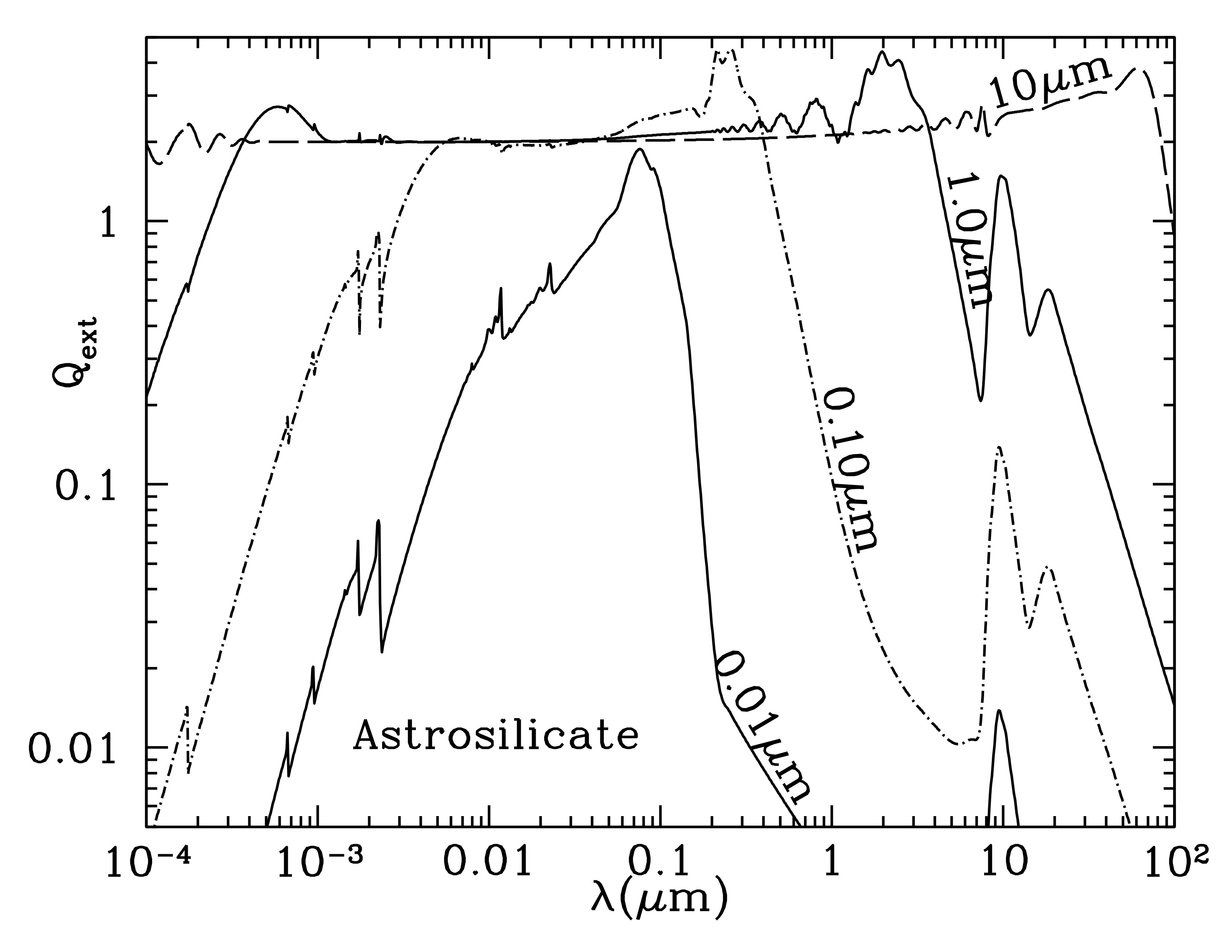

Frequently it’s convenient to work with a dimensionless cross section that is normalized to some characteristic area of the grain. For a spherical grain, the geometric grain cross section is a good one: \(\pi a^2\). Draine adopts the following convention for a non-spherical grain: create a sphere having the same volume \(V\) as the grain material (not including voids) and use the effective cross section of that sphere: \(\pi a_\mathrm{eff}^2\), where $$ a_\mathrm{eff} = \left( \frac{3 V}{4 \pi} \right)^{1/3}. $$ Then we have $$ Q_\mathrm{sca} = \frac{C_\mathrm{sca}}{\pi a_\mathrm{eff}^2} $$ $$ Q_\mathrm{abs} = \frac{C_\mathrm{abs}}{\pi a_\mathrm{eff}^2} $$ and $$ Q_\mathrm{ext} \equiv Q_\mathrm{sca} + Q_\mathrm{abs} $$ and all of the \(Q\) terms are dimensionless.

Index of refraction

The index of refraction will indicate whether a dust grain is better at absorbing or scattering.

This can be done with the complex dielectric function $$ \epsilon(\omega) = \epsilon_r + i \epsilon_r $$ or the refractive index \(m(\omega)\) where \(m = \sqrt{\epsilon}\).

The index of refraction is a complex number with real and imaginary parts $$ m = m_r + i m_i. $$

- The real part \(m_r\) is called the refractive index and determines how much a beam of light is bent (or refracted)

- The imaginary part \(m_i\) is called the absorption index, since it determines how strongly the substance absorbs light.

Both \(m_r\) and \(m_i\) are real and non-negative.

Consider an electromagnetic wave with field strength $$ E \propto e^{i(kx - \omega t)} $$ traveling through a material. The dispersion relationship between wavenumber and frequency will be $$ k = m \frac{\omega}{c}. $$

If the imaginary part of \(m\) is greater than zero, then the power of the electromagnetic wave will decrease as it propagates through the material $$ |E|^2 \propto e^{-2 \mathrm{Im}(m) \omega x/c} $$ and thus the attenuation coefficient for that light will be $$ \kappa(\omega) = 2 m_i \frac{\omega}{c} = \frac{4 \pi m_i}{\lambda_\mathrm{vac}}. $$

Limit that grain much smaller than wavelength of light

Now we will consider the situation where the grain is much smaller than the wavelength of incident radiation. In such a situation, it’s as if the grain is subject to an incident applied electric field that is uniform in space

The efficiency factors have the form

- absorption

$$ Q_\mathrm{abs} = 4 \left ( \frac{2 \pi a }{\lambda} \right) \mathrm{Im} \left [ \frac{m^2 - 1}{m^2 + 2} \right]. $$

which yields an absorption coefficient $$ \kappa_\mathrm{abs} \propto n_\mathrm{gr} a^3. $$ So, you can think of the absorption coefficient as being proportional to the fraction of the volume of space that is occupied by dust.

For scattering, the efficiency factor is $$ Q_\mathrm{sca} = \frac{8}{3} \left ( \frac{2 \pi a}{\lambda} \right)^4 \left | \frac{m^2 - 1}{m^2 + 2} \right |^2. $$ or the relationship that $$ \sigma_\mathrm{sca} \propto a^6 \lambda^{-4} $$ which is characteristic of Rayleigh scattering.

As long as there is any absorption at all, absorption will dominate over scattering in the limit that the grain radius goes to zero. E.g., you can see this by the fact that the optical/UV extinction curve has a shape much closer to \(\lambda^{-1}\) than \(\lambda^{-4}\).

Regime where sizes are comparable

Use Mie theory to calculate the absorption and scattering coefficients. Basically, the electric field inside and outside the sphere can be decomposed into spherical harmonics with appropriate radial functions, and then determine the coefficients by the boundary conditions that you have a plane wave at infinity and that you have continuity at the surface of the sphere. In modern applications, you would write/use a computer program to calculate these coefficients.

Regime where \(2 \pi a \gg \lambda\)

Might want to use Mie theory, but there are some useful approximations. As you take the limit of larger grains relative to the wavelength you get the strange result that $$ Q_\mathrm{ext} \rightarrow 2. $$ Now, if you remember the definition of \(Q_\mathrm{ext} \), this means that the extinction cross-section is twice that of its geometric cross section. It’s as if you had a large opaque bowling ball, but with twice the cross-sectional area. This result is called the “extinction paradox.”

It comes about because of diffraction effects. According to Babinet’s principle the scattering produced by an opaque object is the same as that produced by an aperture of the same size cut into an opaque screen. So the diffraction pattern of an opaque sphere of radius \(a\) is the same as the Airy pattern produced by a hole of radius \(a\) cut into a screen, and in the short-wavelength limit you get \(Q_\mathrm{abs} = 1\) and \(Q_\mathrm{sca} = 1\) so \(Q_\mathrm{ext} = 2\).

Values of the dimensionless extinction coefficient \(Q_\mathrm{ext}\) for amorphous silicate spheres with particle sizes \(a\) of 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 microns, for observational wavelengths ranging from 1 angstrom to 1 mm. At short wavelengths, the smallest grains show discontinuities at the x-ray absorption edges. In the IR, the medium sized grains show prominent silicate absorption features at 9.7 microns and 18 microns (not seen for the largest grains). Credit: Draine Fig 22.6