Telescope Proposals and Time Allocation Committees

Goal: Discuss how the telescope proposal process works, using ALMA as a guide.

This includes

- the technical components to writing and submitting a proposal

- tips on developing and strengthening your scientific idea

- how your proposal is reviewed and graded

Why write a telescope proposal? To get data to answer a scientific question. (Sometimes, the data needed to answer that scientific question might already exist in the archive. In that case, save the time writing a proposal and use the archival data to write your paper).

To start, let’s walk through the example proposal provided on the course Canvas page (Czekala_Proposal.pdf).

Lifecycle of a proposal

This is my own proposal, and it may be helpful to walk through a timeline of the project. This is a Cycle 6 proposal.

- 2018: January and February: Start thinking seriously about ALMA proposals for the upcoming cycle based upon anticipated capabilities that have been hinted at throughout the previous year, through information provided at conferences and other venues, and brainstorming scientific questions that could be addressed with new data.

- 2018: March ~15: Cycle 8 call for proposals announced. This is where the capabilities for the upcoming cycle are definitively announced, along with the official (up-to-date) technical documents, and the proposal deadline is set (usually in mid-late April).

- Speaking for myself, ~1 month is barely enough time to conceptualize, design, make figures for, edit, and submit one proposal even if I am doing nothing else. So, if you are like me, either plan ahead before the call for proposals is announced (relying upon documents from previous cycles), or truly clear your schedule of all other activities (most of the time this is impossible, hence the need to start early).

- 2018 March - April ~20th: Turn brainstormed ideas into concrete proposals, download and examine relevant archival data, make figures, draft text, contact collaborators, iterate on proposal (leaving > 1 week time for comments, preferably 2 weeks), submit proposal

- Summer 2018: ALMA TAC “meets” and ranks proposals

- August 2018: Ranking results released. For the proposal we’re about to review, I learned that I had received a “B” ranking, which means that the proposal would be scheduled for the upcoming cycle, but with priority lower than the “A” ranked proposals.

- October 2018 - September 2019: The observing window for Cycle 6. My scheduled program might be observed anytime in this window, provided it is 1) observable 2) weather is good 3) no highly ranked programs are ahead of me

- October 3rd, 2018: I get a notification that the program was observed, hooray! (For a “B”-ranked program, this wasn’t guaranteed).

- November 2018: Calibrated data available for download from NAASC.

- November 2018 - February 2021: Work on data analysis, writing, etc (among other things). [Proprietary period expired November 2019]. 25 months…

- February 2021: Submit paper to Astrophysical Journal

- March 2021: (Mercifully quick) referee process and acceptance to Astrophysical Journal

Let’s now take a look at the proposal itself and the paper that resulted, and discuss the components.

Components of an ALMA proposal

- Title + Abstract

- Scientific Justification

- Technical Justification

- “Observing Tool” + correlator setup

Discussion questions

- For observationally-oriented projects, what is the minimum time to go from proposal idea to getting data? What is a reasonable time to go from getting data to publication?

- What about the role of archival data in preparing a new proposal? Unpublished archival data (proprietary period has passed)?

What happens in the review process?

Overview of the ALMA Cycle 8 proposal review process

Cycle 8 had 1735 total proposals, of which 253 were selected to be observed as “high priority” (grade A + B). Over 1000 people participated in the review process.

What is the observatory looking for? To do the best science (as defined by the scientific community) with limited resources (time).

Dual anonymous proposals

In recent cycles, ALMA has followed a dual-anonymous proposal strategy. This means that the proposers do not know the reviewers’ identities, nor do the reviewers know the proposers’ identities. This strategy is also employed by HST and JWST review panels.

Dual-anonymous review processes are designed to insulate against many biases (prestige, gender, seniority, …) that may affect the quality of a reviewer’s judgement. Speaking from my own experience from serving as a reviewer on dual-anonymous and non-anonymized panels, I very much prefer the dual-anonymous format. In panel discussions, it reduces “background noise” from the reputation (or lack thereof) of the proposer, removes many political dimensions, and forces the committee to focus solely on the scientific and technical merits of the proposal. In the end, this improves the ability of the observatory to do the best science with limited resources.

What are you asked to do as a reviewer?

The following is from the Cycle 8 Guidelines for Reviewers:

Assessing proposals

Reviewers should assess the scientific merit of the proposals to the best of their ability using the following criteria: The overall scientific merit of the proposed investigation and its potential contribution to the advancement of scientific knowledge.

- Does the proposal clearly indicate which important, outstanding questions will be addressed?

- Will the proposed observations have a high scientific impact on this particular field and address the specific science goals of the proposal? ALMA encourages reviewers to give full consideration to well-designed high-risk/high-impact proposals even if there is no guarantee of a positive outcome or definite detection.

- Does the proposal present a clear and appropriate data analysis plan?

The suitability of the observations to achieve the scientific goals

- Is the choice of target (or targets) clearly described and well justified?

- Are the requested signal-to-noise ratio, angular resolution, spectral setup, and u-v coverage sufficient to achieve the science goals?

In general, the scientific merit should be assessed solely on the content of the proposal, according to the above criteria. Proposals may contain references to published papers (including preprints) as per standard practice in the scientific literature. Consultation of those references should not, however, be required for a general understanding of the proposal.

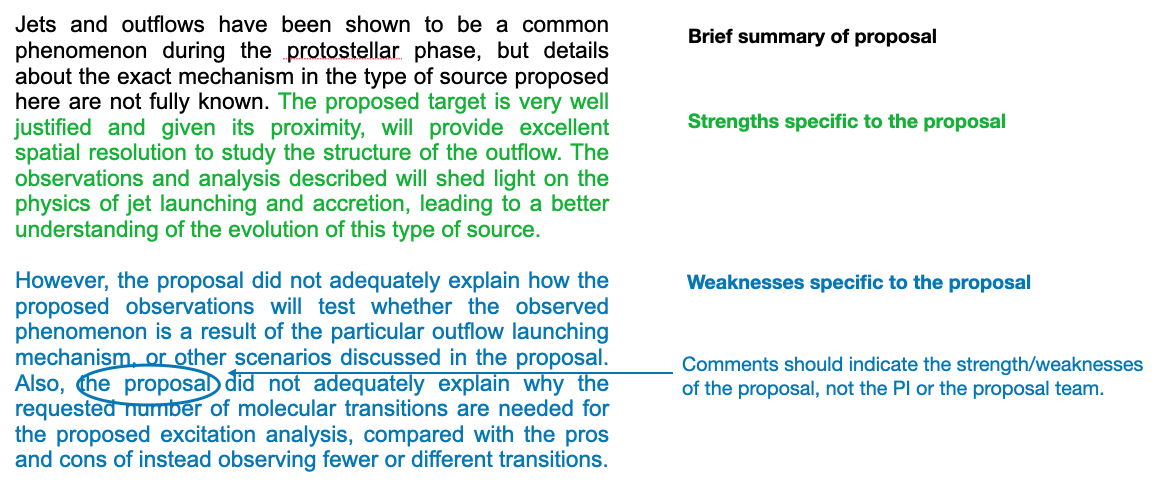

Writing reviews to the PIs

Clear and thoughtful reviews from reviewers can help PIs improve their proposed project and write stronger proposals in the future.

- Summarize both the strengths and weaknesses of the proposal.

A summary of both the strengths and weaknesses can help PIs understand what aspects of the project are strong, and which aspects need to be improved in any future proposal. Reviews should focus on the major strengths and major weaknesses. Avoid giving the impression that a minor weakness was the cause of a poor ranking. Many proposals do not have obvious weaknesses but are just less compelling than others; in such a case, acknowledge that the considered proposal is good but that there were others that were more compelling.

Take care to ensure that the strengths and weaknesses do not contradict each other.

- Be objective.

Be as specific as possible when commenting on the proposal. Avoid generic statements that could apply to most proposals. If necessary, provide references to support your critique. All reviews should be impersonal, critiquing the proposal and not the proposal team. For example, do not write “The PI did not adequately describe recent observations of this source.”, but instead write “The proposal did not adequately describe recent observations of this source.”.

Reviewers cannot be sure at the time of writing reviews whether the proposed observations will be scheduled for execution. The reviews should be phrased in such a way that they are sensible and meaningful regardless of the final outcome.

- Be concise.

It is not necessary to write a lengthy review. An informative review can be only a few sentences in length if it is concise and informative. But, please avoid writing only a single sentence that does not address specific strengths and weaknesses.

- Be professional and constructive.

It is never appropriate to write inflammatory or inappropriate comments, even if you think a proposal could be greatly improved. Use complete sentences when writing your reviews. We understand that many reviewers are not native English speakers, but please try to use correct grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

- Be aware of unconscious bias.

We all have biases and we need to make special efforts to review the proposals objectively. A discussion of unconscious bias is provided here.

- Be anonymous.

Do not identify yourself in the reviews to the PIs. In case of distributed peer review, these reviews will not be checked and edited by the JAO. They will be sent verbatim to the PIs, and they will also be shared with other reviewers during Stage 2. Do not spend time trying to guess who is the proposal team behind the proposal you are reviewing. Your review should be based solely on the scientific merit of the proposal.

- Other best practices.

Do not summarize the proposal: The purpose of the review is to evaluate the scientific merits of the proposal, not to summarize it. While you may provide a concise overview of the proposal, it should not constitute the bulk of the reviews. Do not include statements about scheduling feasibility. If there are any scheduling feasibility issues with the proposal, the JAO will address them directly with the PI. Do not include explicit references to other proposals that you are reviewing, such as project codes. Do not ask questions. A question is usually an indirect way to indicate there is a weakness in the proposal, but the weakness should be stated explicitly. For example, instead of “Why was a sample size of 10 chosen?” write “The proposal did not provide a strong justification for the sample size of 10.” Do not use sarcasm or any insulting language.

- Re-read your reviews and scientific rankings.

Once you have completed your assessments, re-read your reviews and ask how you would react if you received them. If you feel that the reviews would upset you, revise them. Check to see if the strengths and weaknesses in the reviews are consistent with the scientific rankings. If not, consider revising the reviews or the rankings.

An example of a decent (albeit short) review. From the ALMA Cycle 8 Reviewers Guidelines.

For ALMA distributed TAC, you are asked to review 10 proposals for every proposal that you submit.

For something like the JWST TAC, you might be asked to read about 70 proposals for which you are not conflicted. 30-40 of them will be as “primary” or “secondary” reviewer.

There is also an ALMA review panel for proposals asking for more than 25 hours of time, which meets and discusses the proposals.

Tips for writing good proposals

- Background on the topic, beginning broad and narrowing to the question addressed by the proposal

- Previous work on the proposal’s question (not necessarily your own!)

- How new progress can be made

- Proposed observations to address the proposal’s question

- Describe selection of targets and justify their number

- Describe the observations, the analysis of the data, and how they will be interpreted and used to answer the proposal’s question

- In the technical section, describe all details of the observations: instrument, filters, dispersers, apertures, exposure times, positions, dithering/mapping strategy, explanation of how exposure times selected (e.g., to achieve a certain SNR), total observing time, observing constraints (e.g., instrument orientation)

- Justify the telescope; why can’t observations be performed with smaller/other telescopes?

Other miscellaneous thoughts

Good review committees will make sure that the strengths and weaknesses of the proposal are adequately discussed.

Sometimes (especially for highly oversubscribed calls), there are very few weaknesses identified for a proposal. That doesn’t necessarily mean that your proposal should have been accepted over ones that were! In very competitive reviews, it’s common to just have proposals that were a more compelling use of the observatory’s limited resources.

When writing a review, try to put yourself into the shoes of the proposer receiving the comments, and strive to write accurate and constructive comments. Avoid commentary about the individual (in a dual-anonymous review process, this trap is harder to fall into). Rather, focus on the content of the proposal and the scientific plan.

- Reviews tend to be concise (remember, serving on a TAC is usually a voluntary service to the community, and reviewers might need to write and review comments for over 40 proposals).

TAC Review Assignment

At the end of this lecture, you will be provided with a packed of 5 actual ALMA proposals that I have sourced from my generous colleagues.

It is your job to review these as if you were serving on the ALMA time allocation committee.

First, please read the ALMA Guidelines for reviewers document. Then, for each proposal, you will be expected to write a review at least 100 words in length, though it’s not a bad idea to aim for 150 - 200 words.

These reviews are due Monday, November 1st, and are worth 5% of your final grade. In addition, you will be asked to grade each proposal on a numerical scale of 1 to 5 (1 being the best, 5 the worst.)

I will also designate each student as the “primary” and “secondary” reviewer for a proposal. On Wednesday, November 3rd and Friday, November 5th, class will be devoted to a mock TAC discussion. The idea is that, as primary reviewer, you will lead the discussion about the proposal. As secondary reviewer, you will be asked to provide any additional thoughts that the primary reviewer may not have covered. The other TAC members are welcome to comment on any proposal, even if they are not primary or secondary reviewers.

Then, as a TAC, we will decide on a collective ranking of the proposals. Once this is complete, we will examine how the proposals were actually ranked by the real ALMA TAC, and discuss.

ALMA Proposal Final Project

After we complete the review process on Nov 5th, it might be a good time to start thinking about your final project, which will be the scientific justification component of an ALMA proposal (modeled on the Cycle 8 call for proposals). Information on this can be found in the course syllabus.