Grain Temperatures, Physics, and Dynamics

- Draine Ch. 24, 25, 26

We’ve defined temperature as an “internal energy.” For an ensemble of particles, this translated into a statement about their velocity distributions (Maxwellian). For a dust grain, a temperature is a measure of the internal energy present in its vibrational modes and low-lying electronic excitations.

If a dust grain has an internal energy \(E\), then we can define the temperature as that such that for the grain $$ \langle E_\mathrm{int} \rangle_T = E $$ bascially, the temperature defines the average internal energy.

When the internal energy is very small (similar to the level of the first excited state), the idea of temperature becomes difficult to grapple with. But, most grains will have temperatures larger than this, and we can use temperature as a reasonable concept.

We can add or remove energy to a grain through absorption and emission of photons, or by inelastic collisions with atoms and molecules from the gas. (Grain-grain collisions can do this, but they are rare).

- In a diffuse region, grain heating is dominated by absorption of starlight photons.

- In a dark region, grain heating is dominated by inelastic collisions.

The dust grains responsible for the bulk of observed extinction at optical wavelengths are grains with radii \(a > 0.03\,\mu m\) and are considered “classical” macroscopic grains. Absorption/emission of a single quantum photon does not appreciably change the total energy in vibrational or electronic excitations.

There are also ultrasmall particles (down to large molecules) where quantum effects are important.

Radiative heating

After an optical or UV photon is absorbed by a grain, an electron is raised into an excited electronic state. Sometimes the grain will luminesce, where the excited state decays radiatively and emits a photon equal to or less than the absorbed photon.

But, more likely, the electronically excited state will deexcite nonradiatively, such that the energy goes into many vibrational modes as heat. We can calculate the rate of grain heating from absorption of radiation as

$$ \frac{d E}{d t} = \int \frac{u_\nu d \nu}{h \nu} \times c \times h \nu \times Q_\mathrm{abs}(\nu) \pi a^2 $$

i.e., the number density of photons in that frequency bin, photons moving at the speed of light with energy \(h \nu\), and the grain’s absorption cross section.

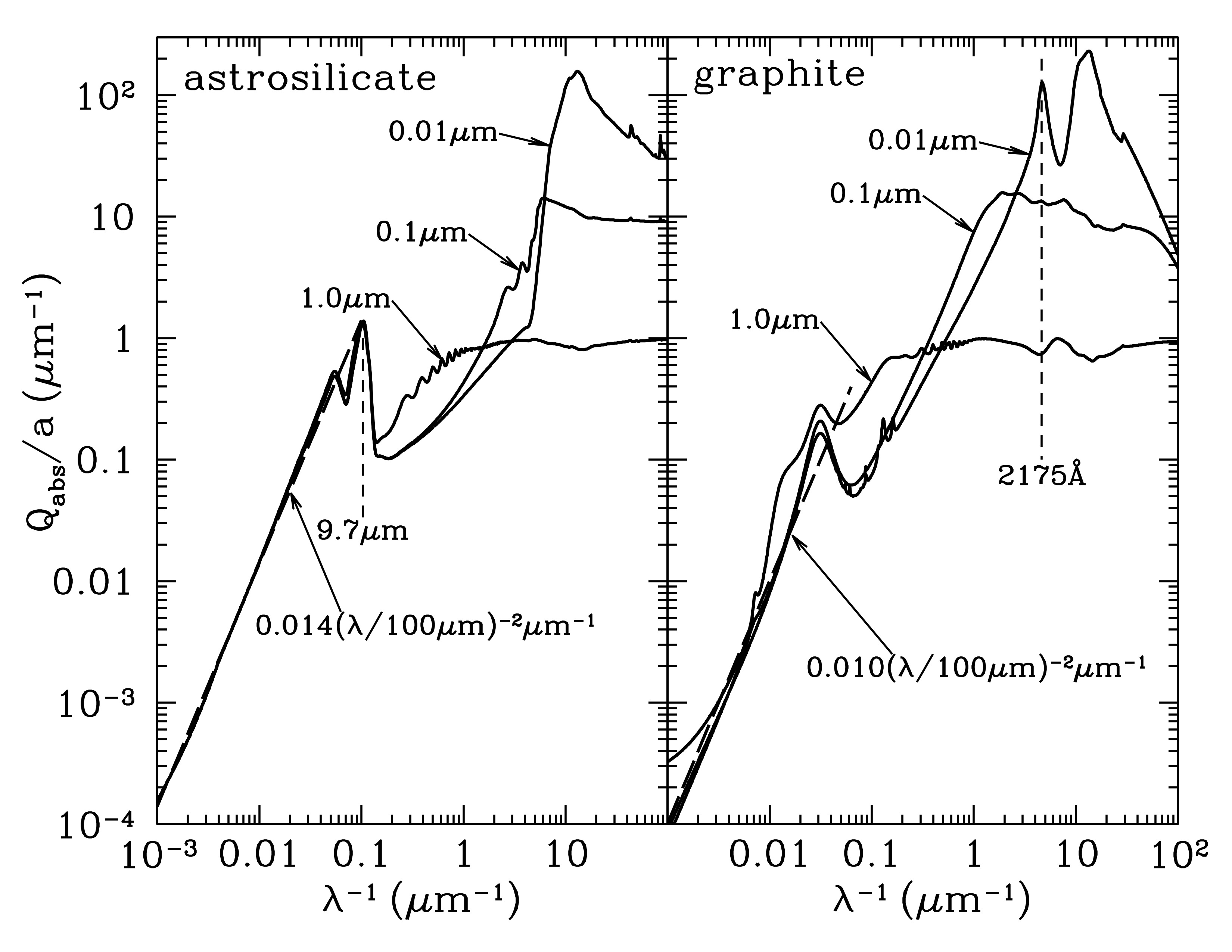

Absorption efficiency divided by grain radius for spheres of amorphous silicate and graphite. Credit: Draine Figure 24.1

Radiative cooling

Grains loose energy by infrared cooling, at a rate $$ \frac{d E}{d t} = \int d \nu 4 \pi B_\nu(T_d) C_\mathrm{abs}(\nu) = 4 \pi a^2 \langle Q_\mathrm{abs} \rangle_{T_d} \sigma T_d^4 $$ where \(\sigma\) is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant and \(\langle Q_\mathrm{abs} \rangle\) is the emission efficiency averaged over some spectrum. We’ll use \(T_d\) for the Plank function of the dust temperature, and \(\star\) for the spectrum of radiation heating the grain.

Steady-state grain temperature

The steady state temperature \(T_{ss}\) can be calculated by the balance of cooling and heating $$ 4 \pi a^2 \langle Q_\mathrm{abs} \rangle_{T_{ss}} \sigma T^4_{ss} = \pi a^2 \langle Q_\mathrm{abs} \rangle_\star u_\star c $$

For a typical interstellar radiation field, and the absorption and emission properties of silicate and graphite, you get steady-state grain temperatures of about 15 - 20 Kelvin.

Ultrasmall dust grains

If the grain is very small, it doesn’t really make sense to define a temperature, since each photon absorption event dramatically spikes what we would otherwise define as temperature. Instead, we need to consider a probability distribution function of temperatures. But, small grains can reach high “temperatures” above 100 K, where they will radiate strongly in the PAH features at 7.7, 8.6, and 11.3 microns.

Infrared emission from grains

In a typical spiral galaxy, about 1/3 of the energy radiated by stars is absorbed by dust grains and then reemitted in the infrared. Though infrared emission is a quantum process, you can approximate it as a “thermal” approach,

$$ j_\nu = \sum_i \int d a \frac{d n_i}{d a} \int d T \left (\frac{d P}{d T} \right){i,a} C\mathrm{abs} (\nu, i, a) B_\nu(T) $$

where you’re summing over the different types of grains.

To calculate \(j_\nu\), you need

- a grain model to provide the grain size distribution for each composition

- the absorption cross sections

- the temperature distribution functions (for large grains, the temperature distribution function is so narrow that you can approximate it via a delta function located at \(T_{ss}\))

Grain Physics: Charging and Sputtering

Grains can be given some charge by collisions. If the grain is neutral, an approaching electron on ion will polarize the grain, attracting the projectile to the grain. This can improve the charging rate for very small grains.

Photoelectric emission

When an energetic photon is absorbed by the grain, excites an electron to a sufficiently high energy such that the electron escapes from the grain. When an electron is ejected this way, it’s called a “photo electron.”

The photoelectron yield \(Y_\mathrm{pe}(h \nu, a , U)\) is the probability that a photon of energy \(h \nu\) will result in a photoelectron. It appears that UV radiation in average starlight background is able to drive grains with radii \(a > 0.01 \mu m\) to positive potentials.

Sputtering

If the gas temperature is sufficiently high, then impinging atoms or ions will erode the grain, one atom at a time. This process is called sputtering. It also happens on the surfaces of moons in our solar system. In the ISM, sputtering rates can dictate grain lifetimes, for \(10^5\) yrs near a supernova remnant. In a galaxy cluster, \(10^7\) yr, which is short compared to the cluster age.

Grain dynamics

We’ll cover the list of forces and torques that act upon grains. These are what govern grain dynamics.

- grain motion can decouple the movement of dust from gas

- rapid motion can lead to grain destruction

- moving grains may help couple the neutral gas to the magnetic field where fractional ionization might be low (because grains can be charged)

Gas drag

Aerodynamic gas drag. There is a slowing down time, or “drag time” of $$ \tau_\mathrm{drag} = \frac{M_\mathrm{gr} v}{F_\mathrm{drag}}. $$ In diffuse clouds, gas drag can decelerate grains on relatively short timescales of only \(10^5\) yr.

Lorentz force

If grains have a velocity component transverse to the local magnetic field, then they will experience a Lorentz force.

Radiation pressure and recoil forces

The interstellar radiation field is, in general, quite anisotropic (I mean, look around). The radiation pressure force on a grain is $$ F_\mathrm{rad} = \langle Q_\mathrm{pr} \rangle \pi a^2 \Delta u_\mathrm{rad}. $$ Radiation pressure can drive grains through the gas with appreciable velocities.

If the grain preferentially ejects atoms or electrons from the preferentially illuminated side of the grain, then the recoil can be large and accelerate the grain.

Poynting-Robertson effect

Special Relativistic effect. Consider a dust grain orbiting a star.

Because of the abberation of starlight, in the instantaneous rest frame of the orbiting particle, the radiative flux from the star has a component in the direction antiparallel to the motion of the grain. The radiation acts to reduce the orbital momentum of the particle, and leads to an orbital decay that depends on the grain size.

For micron sized particles, PR drag can induce orbital decay of less than a Gyr for particles up to 10 cm in size.

Suprathermal rotation of large grains

We would think classical grains would just be dominated by random collisions with gas atoms and you’d have the rotation temperature of the grain approximately equal to the gas temperature.

However, because the ISM is not in LTE, interstellar grains act as heat engines, meaning they can attain suprathermal rotation rates where \(T_\mathrm{rot} \gg T_\mathrm{gas}\). This can happen by a variety of processes that impart a systematic torque on the grain.

- Formation of molecular hydrogen on the grain surface, followed by impulsive ejection of said \(H_2\).

- Emission of photoelectrons from grains exposed to UV radiation

- Irregular grain surfaces

- Radiative torques due to absorption and scattering of starlight by irregular grains

Rotation of small grains: microwave emission

For the very smallest grains \(a \lesssim 0.001\,\mu m\), rotational dynamics is complex. Any one of the following processes has an important effect on the angular momentum

- random collisions with neutral gas atoms

- collisions of neutral or negatively charged grains with positive ions

- fluctuating electric fields due to passing ions acting on the permanent electric dipole moment of the grain

- angular momentum deposition by absorbed starlight photons

- angular momentum loss to radiated IR photons

- angular momentum loss in electric dipole radiation from the spinning grain

Alignment of Interstellar dust

Interstellar grains are observed to be systematically aligned with their short axis tending parallel to the local magnetic field. Still an open line of research, but the problem involves two separate problems of

- align grain angular momentum with the magnetic field

- align nonspherical body of the grain with the grain angular momentum