Heating and Cooling of HII regions

References:

- Draine Ch. 27

- Ryden and Pogge Ch. 4.3

Now that we’ve taken some time to introduce and discuss dust, we’ll return to H II regions and discuss heating and cooling.

H II regions are regions of photoionized gas around hot stars. Thus far, we’ve just asserted that the temperatures of these regions were around \(10^4\) K, and introduced nebular diagnostics to allow us to measure those temperatures. In today’s lecture, we’ll be discussing the heating and cooling mechanisms that regulate the temperature.

The dominant heating mechanism is photoionization. Photoionizing photons have energies larger that the ionization energy, the resulting photoelectron will have nonzero kinetic energy and add to the thermal energy of the gas.

Recombination processes, primarily radiative recombination, are removing electrons from the plasma (along with the kinetic energy they had). Thermal energy is also lost when an electron collisionally excites ions from lower to higher energy levels (followed by the emission of photons).

The balance of these processes sets the temperature of the gas.

Heating by photoionization

Photoelectric absorption creates a photoelectron with some kinetic energy $$ X^{+r} + h \nu \rightarrow X^{+r+1} + e^- + KE $$

Let \(\sigma_{pe}(\nu)\) be the photoionization cross section for \(X^{+r}\) in its ground electronic state. Given some radiation field \(u_\nu\), how can we calculate the probability per unit time for photoionization? i.e., units of 1/s?

Let’s walk through how we set up an integral, using the cross section, the speed (c), and the energy density $$ \zeta(X^{+r}) = \int_{\nu_0}^\infty \sigma_\mathrm{pe}(\nu) c \left [ \frac{u_\nu}{h \nu}\right] d \nu. $$

How much kinetic energy is injected into the gas? Well, \(h \nu_0\) is the threshold energy for photoionization from the ground state. Therefore, if a photon with \(h \nu\) does the photoionization, then \(h \nu - h \nu_0\) is injected into the plasma. We can calculate the heating rate (ergs/cm^3) by calculating the kinetic energy released per volume per photoionization event as $$ \Gamma_\mathrm{pe} = n(X^{+r}) \int_{\nu_0}^\infty \sigma_\mathrm{pe}(\nu) c \left [ \frac{u_\nu}{h \nu}\right] (h \nu - h \nu_0) d \nu. $$

The mean energy of each photoelectron is $$ E_\mathrm{pe}(X^{+r}) = \frac{\Gamma_\mathrm{pe}}{n(X^{+r}) \zeta(X^{+r})} $$ which depends on the spectrum of photons responsible for photoionization. If we assume that the star’s radiation field can be approximated as blackbody with some color temperature \(T_c\), then we can define the dimensionless ratio $$ \varphi \equiv \frac{E_\mathrm{pe}}{k T_c} $$ For different temperature stars, there will correction factors for photoelectron energy weighted by the blackbody spectrum \(\varphi_0 k T_c\) and the average photoelectron energy \(\langle \varphi \rangle k T_c\), but they are order unity across a wide range of stellar temperatures.

The heating rate depends on the abundance of the species that is being ionized. If the H II region is in photoionization equilibrium, then $$ \zeta(X^{+r}) n(X^{+r}) = \alpha n_e n(X^{+r+1}). $$ If you recall, \(\alpha\) is the rate coefficient for recombination. This can be used to obtain the local heating rate $$ \Gamma_{pe} = \alpha n_e n(X^{+r + 1}) \varphi k T_c. $$ The rate per unit volume of injection of photoelectron energy rate is equal to the recombination rate per unit volumen times the mean photoelectron energy.

In an H II region, the dominant element H will be nearly fully ionized, so \(n(H^+)\approx n_H\), and the rate due to photoionization of H is $$ \Gamma_\mathrm{pe}( H \rightarrow H^+) \approx \alpha_B n_H n_e \varphi k T_c. $$

Other heating processes

Here are a few other heating processes that can contribute.

- Photoelectric emission from dust: dust grains absorb photons, then produce energetic photoelectrons. This effect is important when the radiation field has lots of photons between 10 and 13.6 eV… too weak to ionize H, but able to ionize a dust grain AND there is enough dust present to absorb photons.

- Cosmic Rays: interaction w/ bound electrons (ejecting energetic secondary electron) and transfer of KE to free electrons by elastic scattering, \(\Gamma_\mathrm{CR}\).

In normal H II regions, heating of the gas is dominated by photoionization of H and He, so we usually just refer to \(\Gamma \approx \Gamma_\mathrm{pe}\). The photoionization heating is dependent on the electron density, the ion density, nd the temperature (UV intensity) of star doing the ionizing.

Cooling processes

Consider the balance between heating and cooling processes when the plasma is in ionization equilibrium—every ionization event is balanced by a recombination event.

The total cooling rate is denoted by \(\Lambda\) and has units of (ergs/cm^3). We’ll examine some of the sub-contributions.

Recombination radiation

Every time an electron recombines with an ion, the plasma loses the kinetic energy of the recombining electron. The rate per unit volume at which thermal energy is lost is $$ \Lambda_\mathrm{rr} = \alpha_B n_e n(H^+) \langle E_\mathrm{rr} \rangle $$ where \(\langle E_\mathrm{rr} \rangle\) is the mean KE of the recombining electrons.

Free-Free Emission

Free electrons scattering off of free ions produce free-free emission. If we’re in a pure H plasma at 10^4 K, then the free-free emission per recombining electron is $$ \frac{\Lambda_\mathrm{ff}}{n_e n(H^+) \alpha_B} = 0.54 T_4^{0.37} k T. $$ Where \(\Lambda_\mathrm{ff} \) is the power per unit volume given by (Ch 10.12). For T of 10^4, then radiative recombination and free-free emission together cause the plasma to lose about \(\sim k T\) of kinetic energy per Case-B recombination.

Collisionally-Excited Line Radiation

In an H II region, most H will be ionized.

If there is He or He^+, the energy of the first excited state is quite far above the ground state, so it’s rare that it will be collisionally excited for any relevant thermal plasma.

But if there are heavier metals, like oxygen, then there may be ions like O I, O II, or O III that have energy levels that can be collisionally excited by electrons with kinetic energies of just a few eV (as we studied in the nebular diagnostics lecture). And then they will radiate via lines, and cool the gas.

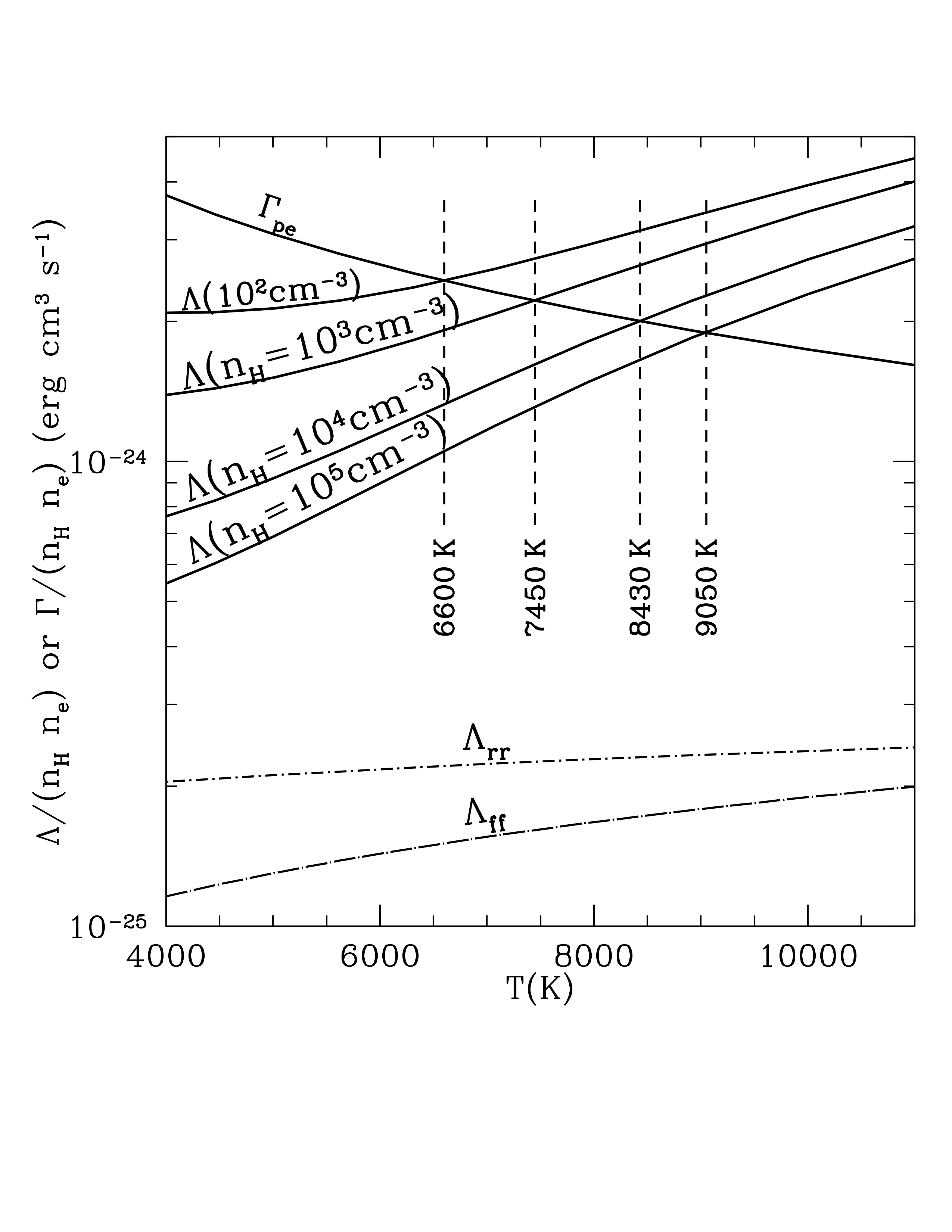

(If the collisional excitation is immediately followed by a collisional deexcitation, then the kinetic energy of the gas is unchanged.)

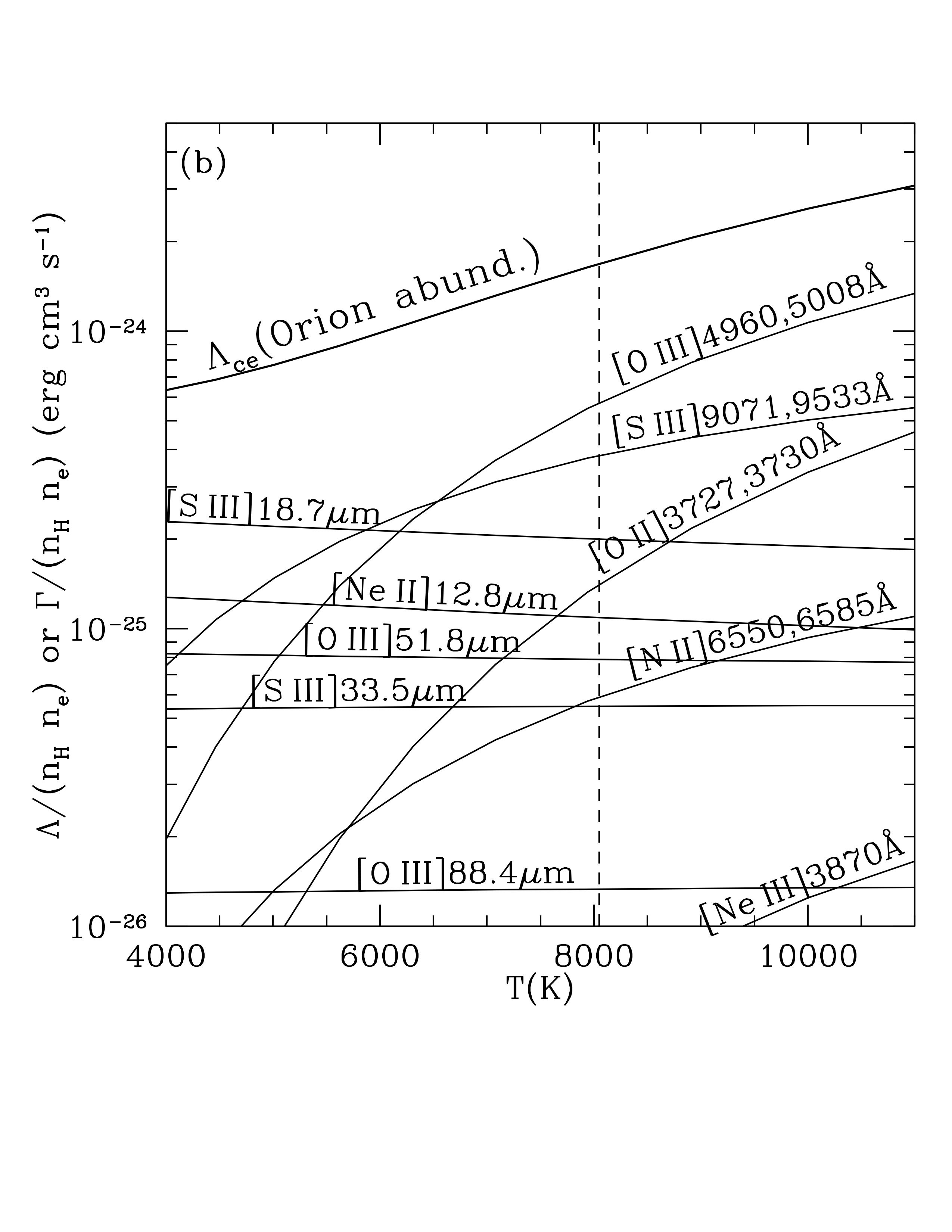

Some of the principal collisionally excited cooling lines in H II regions are N II, O II, O III, Ne II, S II and S III.

Thermal equilibrium

The gas will stabalize at a temperature where heating rate balances the total cooling rate $$ \Gamma(T) = \Lambda(T). $$

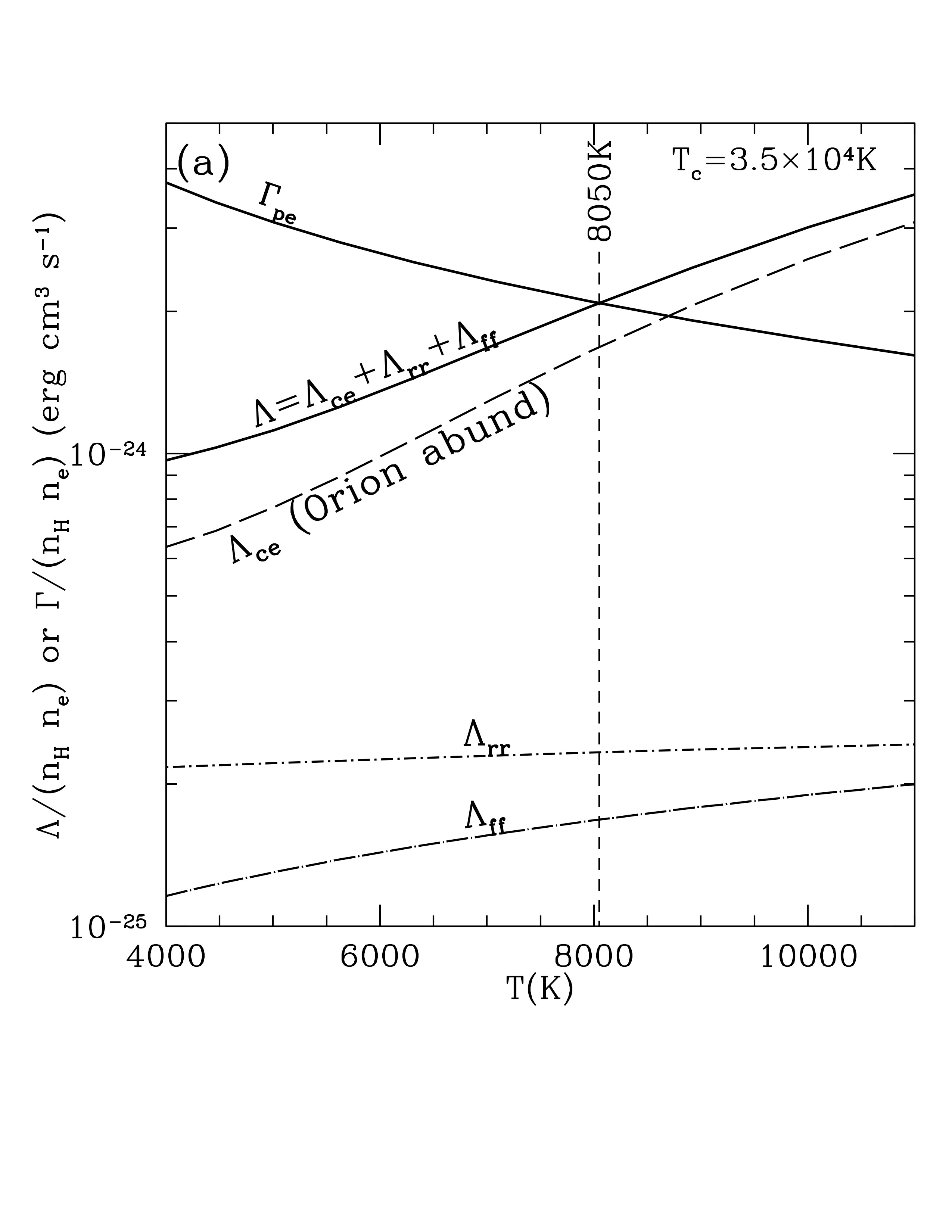

When you investigate each of these processes in detail for an average H II region, you get a steady-state temperature of 8,000 K.

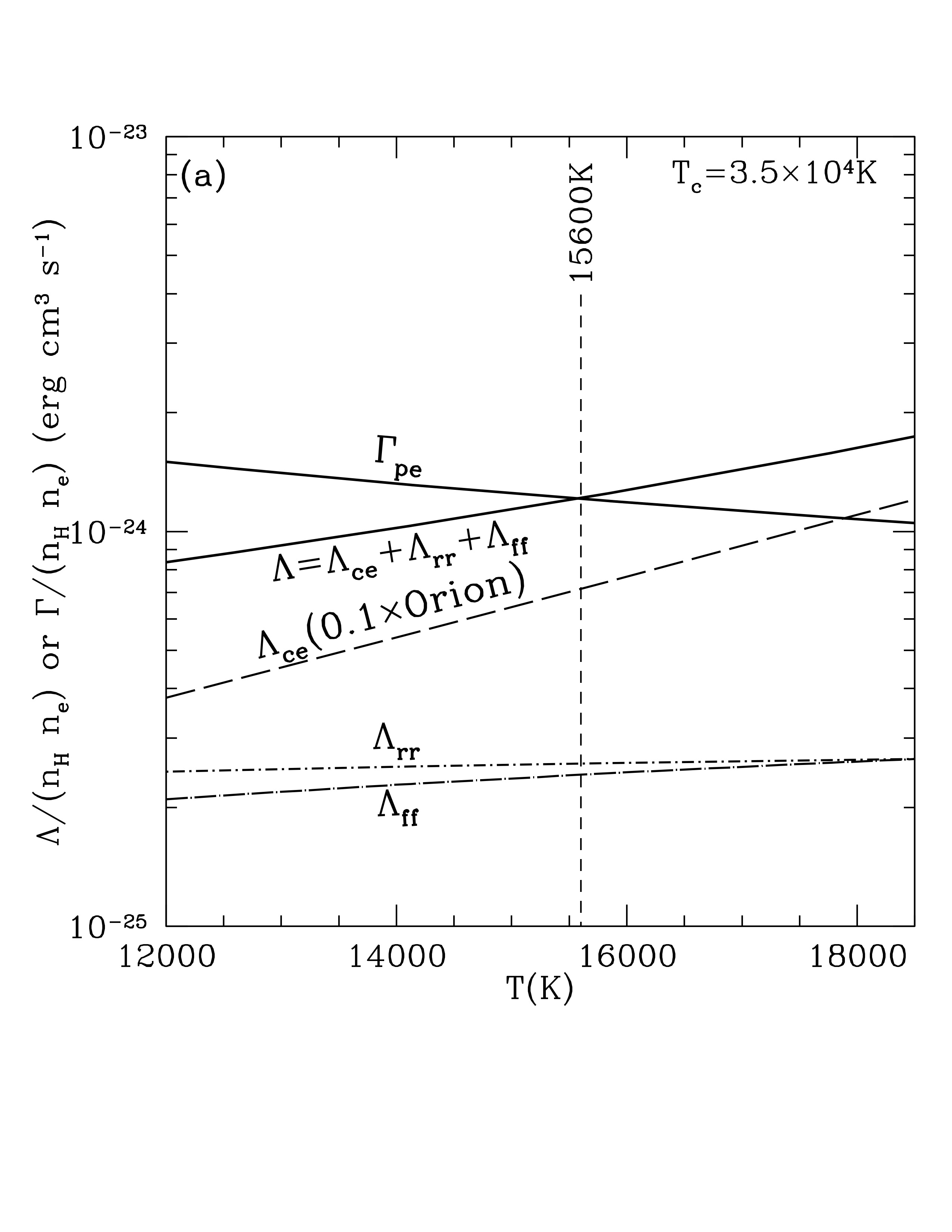

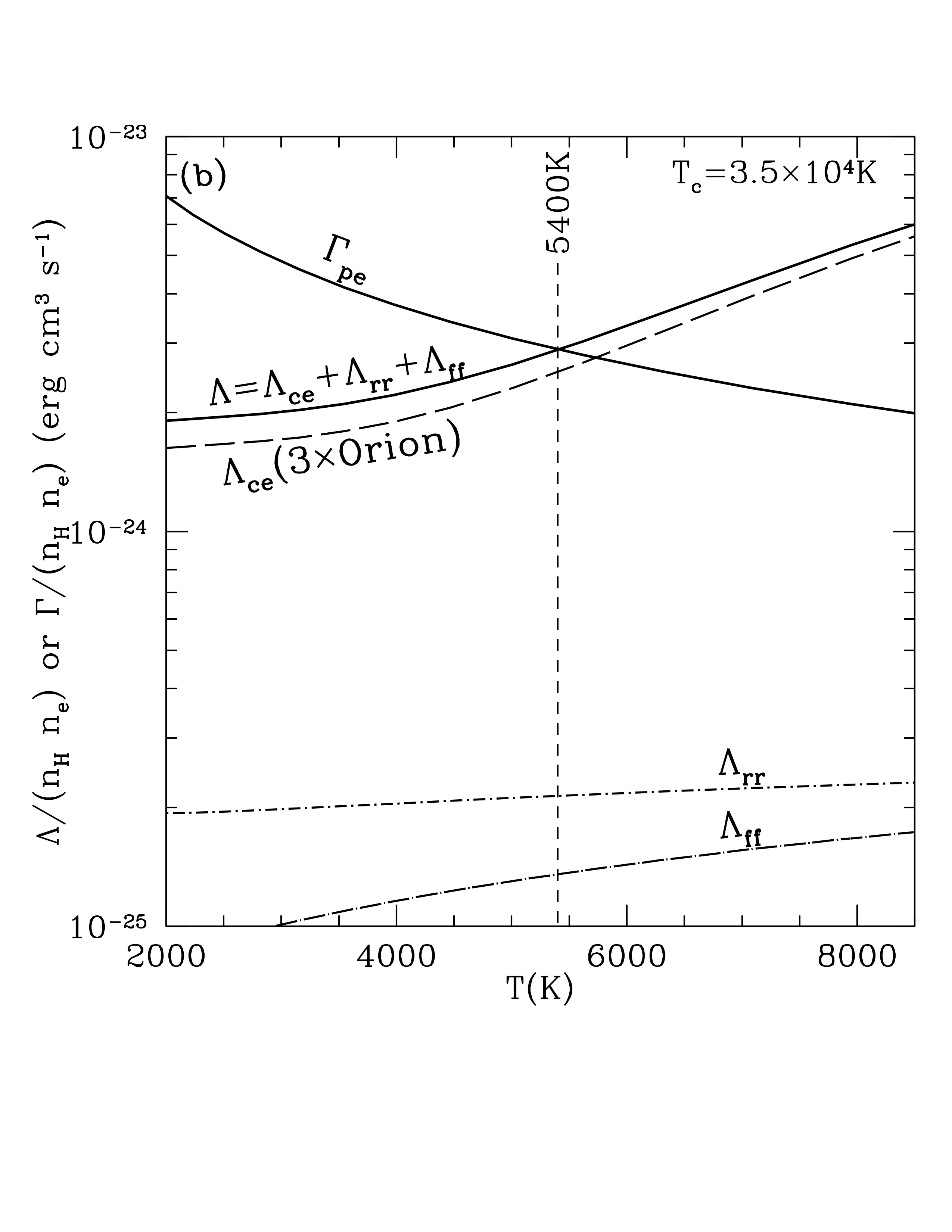

If you fiddle with the metallicities, and thus the abundance of cooling species, the steady state temperature changes. In a low metallicity galaxy, for example, the equilibrium temperature rises to 15,000 K. But if you raise the heavy element abundances by a factor of three, such as in the central region of a mature spiral galaxy, then the H II region temperature is 5,000 K.

Photoelectric heating function \(\Gamma_\mathrm{pe}\) and radiative cooling function \(\Lambda\) as function of gas temperature \(T\) in an H II region with Orion-like abundances and density \(n_H = 4000\) cm^-3. Heating and cooling balance at T approx 8050 K. Credit: Draine Fig 27.1a Contributions of the individual lines to the loss from collisional excitation. Credit: Draine Fig 27.1b Photoelectric heating function \(\Gamma_\mathrm{pe}\) and radiative cooling function \(\Lambda\) as function of gas temperature \(T\) in an H II region with abundances that are only 10% that of Orion. Equilibrium occurs at 15,000 K. Credit: Draine Fig 27.2a Photoelectric heating function \(\Gamma_\mathrm{pe}\) and radiative cooling function \(\Lambda\) as function of gas temperature \(T\) in an H II region with abundances that are enhanced 3 times relative to Orion. Equilibrium occurs at 5,000 K. Credit: Draine Fig 27.2b Cooling function \(\Lambda(T)\) for different densities. The gas is assumed to have Orion-like abundances and ionization conditions. As the gas density is varied from low to high, the equilibrium temperature also varies from low to high because of collisional deexcitation of excited states. Credit: Draine Fig 27.3