Molecular Hydrogen

References

- Ryden and Pogge Ch. 7.4

- Draine Ch. 31

In this lecture, we’re going to take a deep dive into molecular hydrogen, which will set us up for the next lecture on molecular clouds, observation, chemistry, and ionization.

Formation Mechanisms

Direct

Why does molecular hydrogen exist in the ISM at all? The direct formation $$ H + H \rightarrow H_2 + h \nu $$ has such a small rate coefficient that the reaction can be ignored completely in ISM chemistry. The three-body reaction $$ 3H \rightarrow H_2 + H + KE $$ can occur, but the rate is also negligible at interstellar or intergalactic densities. (This is possible at the densities of a protostar or protoplanetary disk, however).

The process by which two hydrogen atoms bond in the ISM is called direct radiative association $$ H + H \rightarrow H_2^* \rightarrow H_2 + h \nu. $$

Two hydrogen atoms meet to create an excited hydrogen molecule \(H_2^*\) that is unbound; it needs to emit a photon with enough energy to leave it in a bound state, otherwise it will break apart.

The lifetime of the excited hydrogen molecule (until it breaks apart) is exceptionally short, approximately one vibration period \(\sim 2 \pi / \omega_0 \sim 10^{-14}\) s.

Because the hydrogen molecule has no electric dipole moment, the probability that it will emit a photon is small. One possibility is via rotational quadrupole transitions, which have \(A_{ul} \sim 10^{-11}\) s. So to form a hydrogen molecule via this, you multiple the probability to emit during the lifetime of the excited hydrogen molecule, and get a probability of $$ p \sim A_{ul} (2 \pi / \omega_0) \sim 10^{-25} $$ of emitting a photon before it falls apart. This leads to a miniscule rate coefficient \(k_\mathrm{dra} 10^{-23}\;\mathrm{cm}\;\mathrm{s}^{-1}\), and therefore at densities typical of the interstellar medium.

Pure gas (not that fast)

Terminology:

- recombination: when a free electron binds to a positive ion

- attachment: when a free electron binds to a neutral atom or negative ion

- ionization: when an electron is stripped from a neutral atom or positive ion

- detachment: when an electron is stripped from a negative ion

In pure gas, \(H_2\) is made via a two-step process:

- Produce negative hydrogen ions by radiative attachment

$$ H^0 + e^- \rightarrow H^- + h \nu $$

This is a slow process (not as slow as direct radiative association, though), with rate coefficient \(k_\mathrm{ra} \approx 10^{-16}\).

The next step (is more rapid) is the production of molecular hydrogen by associative detachment $$ H^- + H^0 \rightarrow H_2 + e^- $$ this step has a rate coefficient of \(k_\mathrm{ad} \approx 10^{-9}\,\mathrm{cm}^3\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}).

This two-step process is hindered by the fact that the intermediate product \(H^-\) is a very fragile ion, it only takes 0.77 eV to detach one of the electrons. In most of interstellar space, the photodetachment rate of \(H^-\) is $$ \zeta_\mathrm{det} \approx 10^{-7}\; \mathrm{s}^{-1} \approx 8.5 \;\mathrm{yr}^{-1}. $$

So, associative detachment (and the resulting production of hydrogen molecules) will dominate over photodetachment when $$ n_\mathrm{H\,I} > \frac{\zeta_\mathrm{det}}{k_\mathrm{ad}} \approx 70\,\mathrm{cm}^3 $$ That’s pretty dense, so in most of the ISM, an \(H^-\) ion will undergo photodetachment before it has the opportunity to make an \(H_2\) molecule.

Without any dust, though, this is dominant channel of molecular hydrogen formation (such as in the early universe).

Grain assisted (grain catalysis)

Whenever dust grains are present, they form the dominant mechanism for making molecular hydrogen, called grain catalysis.

Compared to low-density interstellar gas, the surface of a dust grain is a frenzied lab of chemical activity. Let’s unpack why.

Terminology

- adsorption: atoms sticking to the surface of a grain

- desoprtion: atoms (or molecules) escaping from the surface of a grain

When a hydrogen atom collides with a grain, there is some probability that it will stick, with the modulation that

- slower atoms are more likely to stick

- hot grains are less sticky

- smaller grains are less sticky

- some dependence on composition

For typical molecular cloud conditions, the probability of sticking (adsorption) is about 30% for a 0.1 micron grain. That’s pretty high!

Once the hydrogen atom is stuck to the surface of the grain, it’s held there by the relatively weak van der Waals force. The binding energy is large enough such that the atom doesn’t immediately evaporate from the grain’s surface, however, it’s also small enough such that the atom can skitter its way across the grain surface in a thermally driven random walk. This is called surface diffusion.

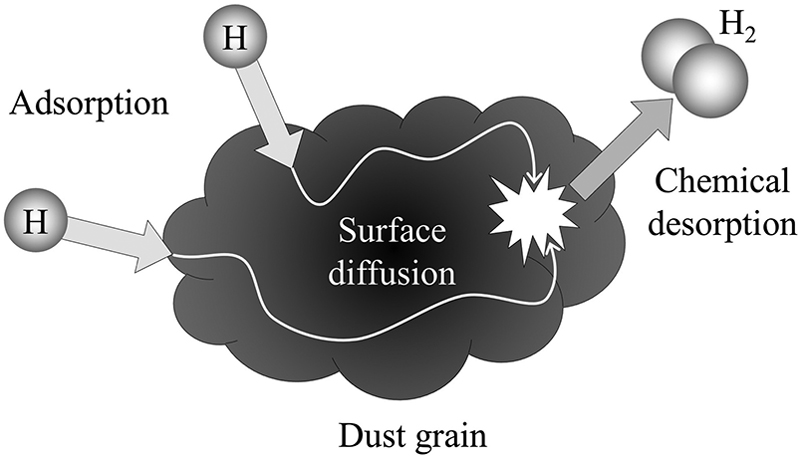

Atoms adsorb onto the surface of a grain, diffuse until they meet another atom, and sometimes form a molecule. Credit: Ryden and Pogge Figure 7.4, following Dulieu et al. 2013

If, during the random walk, the atom encounters another H atom, they can bond to form a hydrogen molecule. The energy released by this reaction will allow the new molecule to escape from the surface (desorption).

To calculate the formation rate, we need to define a grain cross section, assume some grain size distribution, and average over the velocity distribution of hydrogen atoms (thermalized), and then incorporate a probability that it sticks to the dust grain.

Carrying out these calculations using state of the art assumptions leads to the conclusion that dust grains are converting atomic hydrogen into molecular hydrogen on a characteristic timescale of 13 Myr.

Destroying Molecular Hydrogen

Photodissociation is the main way by which molecular hydrogen is destroyed. Because we are dealing with a hydrogen molecule, though, the path is a bit more complicated than you would otherwise expect.

First, let’s look at the potential of the molecule.

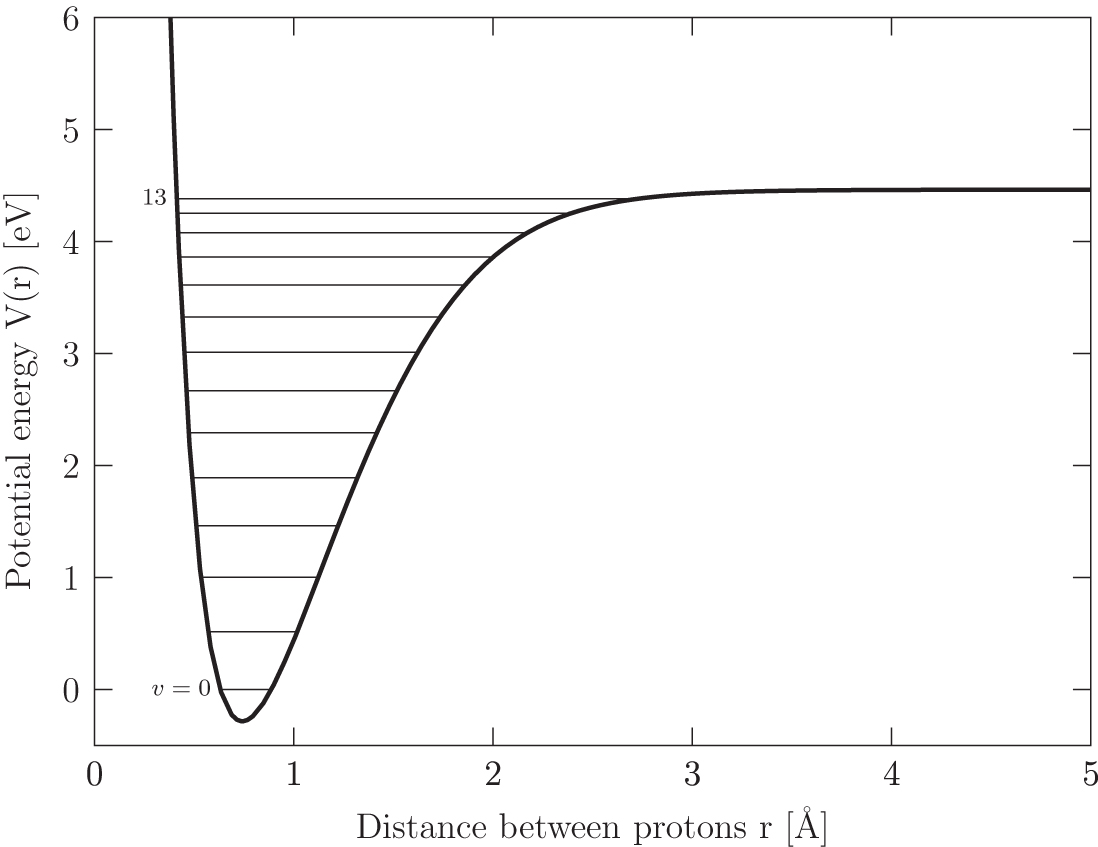

We can look at the potential of the \(\mathrm{H}_2\) molecule as a function of \(r\), the distance between the two protons. The bound vibrational energy levels \(v = 0 \rightarrow 13\) are depicted as horizontal lines. Credit: Ryden and Pogge Fig 7.1, Data from Sharp 1971

In theory, we could just hit a hydrogen molecule with a photon with energy \(h \nu > 4.5 \)eV, lifting it to an unbound potential energy. The problem is that this transition is an electric quadrupole transition, which has a small transition probability.

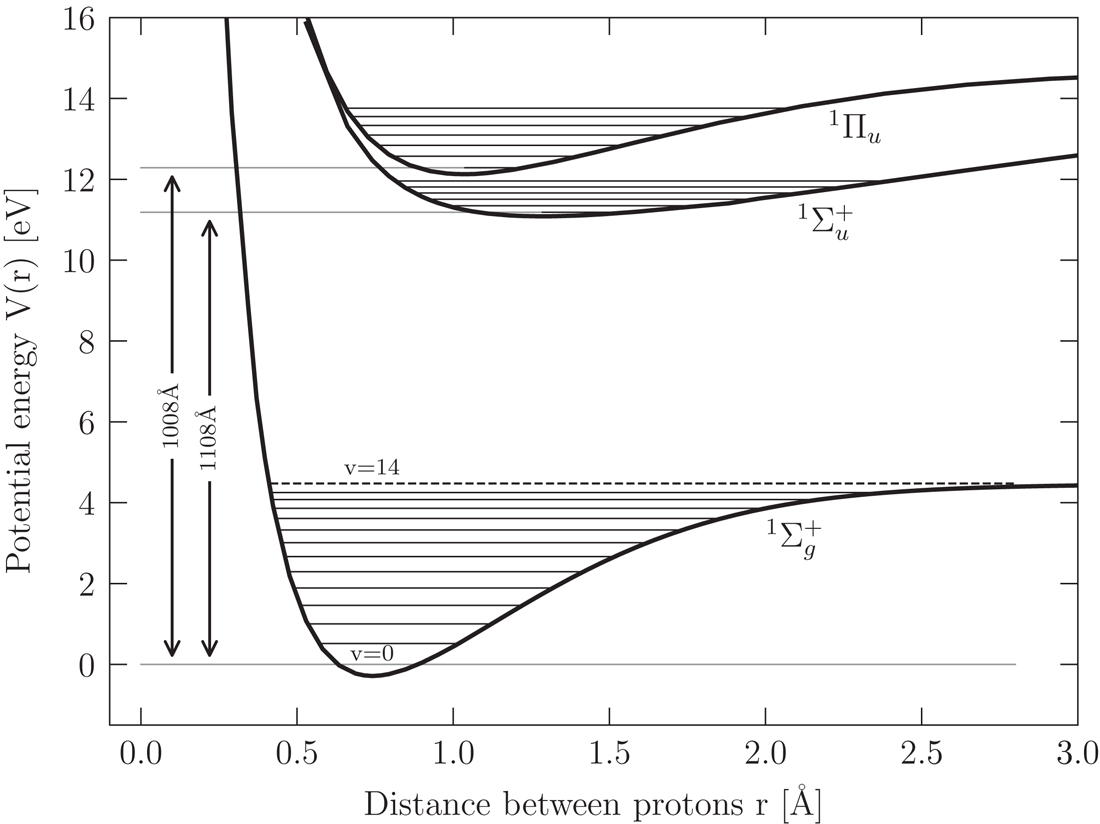

The main process by which molecular hydrogen is dissociated is a two-step process. Let’s look at the potential energy curve for the ground electronic state of molecular hydrogen, as well as for the first and second excited electronic states.

Schematic diagram of the potential energy curves for the ground electronic states and the first and second excited electronic states of molecular hydrogen. Credit: Ryden and Pogge 7.5, data from Sharp 1971.

- Difference between ground state, \(v = 0, J=0\) and first electronic excited state \(v = 0, J=0\) is 11.18 eV, slightly higher than the 10.2 eV Lyman alpha line. This is a permitted transition with a large transition probability.

- Once in the first excited state, the transitions between various vibrational and rotational in this state and the various vibrational and rotational states in the electronic ground state are called Lyman band.

- The transitions between the second electronic state and ground electronic state are called Werner band.

Both Lyman and Werner band bands lie in energy range 11.18 to 13.60 eV.

Once in the first electronic state, it can transition back down to the ground electronic state. But, about 12% of the time, it can also transition to a vibrational state with \(v > 14\), which is unbound, the hydrogen atoms fly apart and dissociation is complete.

Relevant timescales and densities

- The first step, radiative excitation of \(\mathrm{H}_2\) to an excited electronic state, requires a photon with energy in the wavelength range 912 to 1108 angstroms. In the solar neighborhood, these photons are produced by hot stars.

Because of the Lyman and Werner levels, the cross section for a hydrogen molecule is a complicated function of energy. But, using the energy density of the solar neighborhood and incorporating the dissociation fraction, the rate of dissociation is $$ \zeta_\mathrm{dis} \approx 4.2 \times 10^{-11}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}. $$

So the typical timescale for photodissociation of molecular hydrogen is \(1/\zeta_\mathrm{dis}\), or about \(10^3\) yr, about 4 orders of magnitude quicker than the \(10^7\) yr timescale for creation of molecular hydrogen by grain surface catalysis.

The equilibrium abundance of molecular hydrogen is determined by a balance between the slow creation of \(\mathrm{H}_2\) on the surface of grains and the quick destruction of molecular hydrogen by UV photons from stars. If you work out the equilibrium densities and assume that the UV radiation field inside molecular clouds were the same as outside of it, you find that molecular hydrogen should be pretty rare, only dominating over atomic hydrogen when the density was greater than

$$ n_\mathrm{H} \sim 10^6\,\mathrm{cm}^{-3} $$

But, observations tell us that molecular hydrogen formation dominates over atomic hydrogen at densities as low as \(n_\mathrm{H} \sim 300\,\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\). Why?

This is because of self-shielding, whereby UV photons in the range \(h \nu = 11.18 \rightarrow 13.60\) eV are absorbed by hydrogen molecules in the outer layer of the cloud, preventing them from reaching hydrogen molecules in the cloud center. (Remember, these “shield” hydrogen molecules aren’t immediately dissociated… the dissociation only occurs some fraction of the time when the decay reaction is down to a \(v > 14\) state, which is unbound).

Self-shielding becomes important when you have molecular hydrogen column density greater than \(10^{14}\,\mathrm{cm}^{-2}\). The interiors of molecular clouds are mostly saved from photodissociation by a self-sacrificing layer of gas about 0.1 parsec thick, and with density \(n_\mathrm{H} \sim 300\,\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\).

Things change, though, when newly formed stars are of spectral types O, B, or A and are hot enough to pour out photons with energies \(h \nu > 11.18\) eV, which form photodissociation regions around the hot stars.

Photodissociation regions

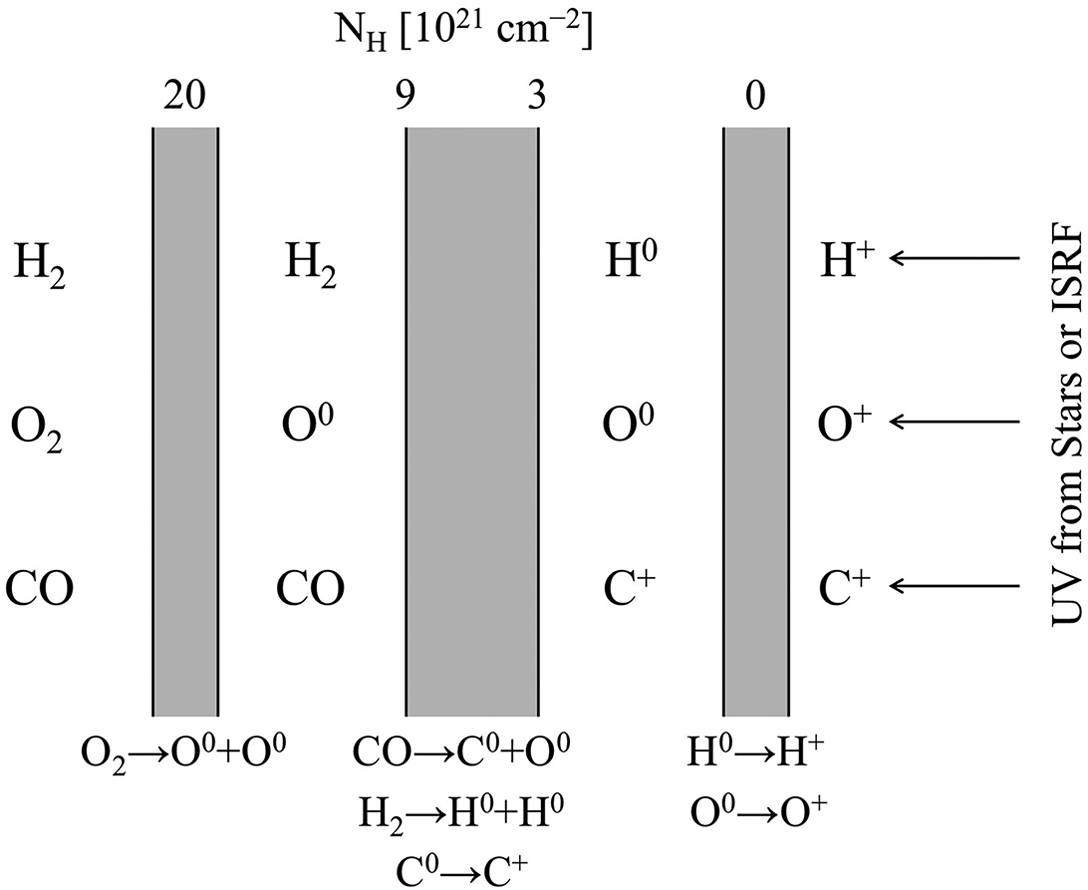

Have an obvious parallel to H II regions, and in fact you can have a complicated structure of ionized, neutral atoms, and molecular hydrogen.

Schematic diagram of a photodissociation region. The shielded molecular gas is on the left, the source of UV photons is on the right. The numbers at the top of the diagram represent the column density of hydrogen measured from the ionization front. Credit: Ryden and Pogge Fig 7.6

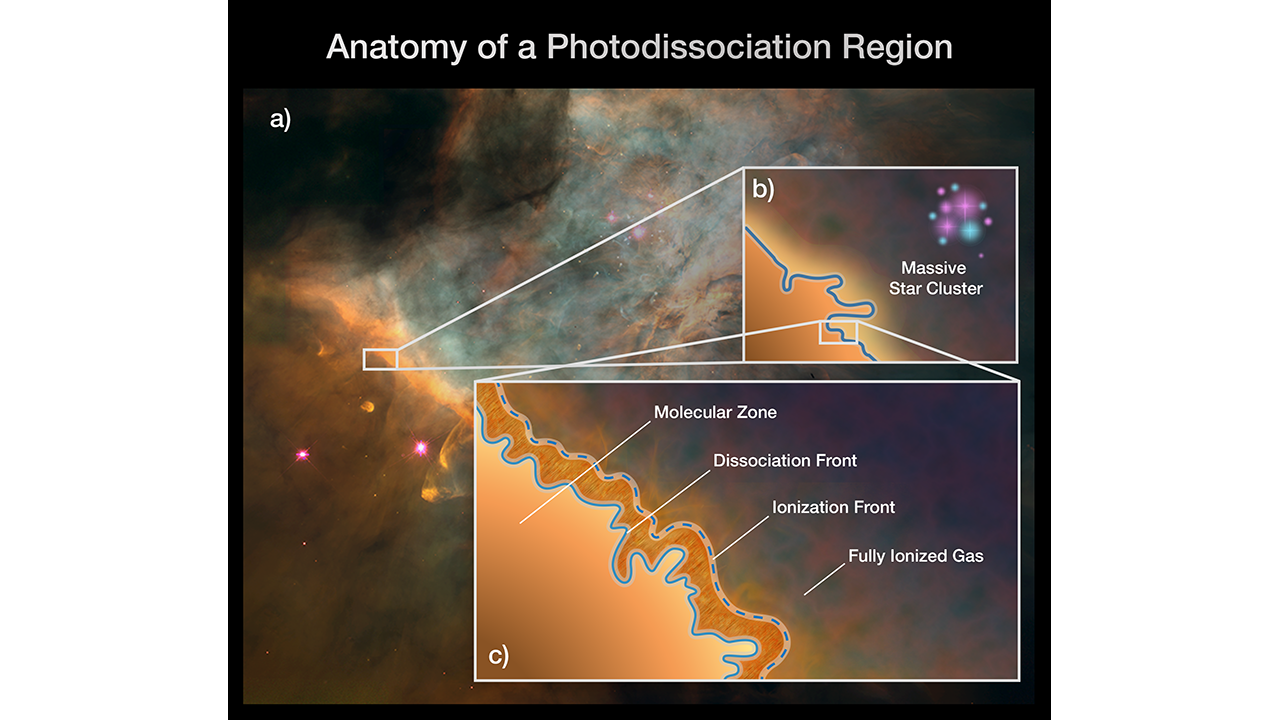

This graphic depicts the stratified nature of a photodissociation region (PDR) such as the Orion Bar. Once thought to be homogenous areas of warm gas and dust, PDRs are now known to contain complex structure and four distinct zones. The box at the left shows a portion of the Orion Bar within the Orion Nebula. The box at the top right illustrates a massive star-forming region whose blasts of ultraviolet radiation are affecting a PDR. The box at the bottom right zooms in on a PDR to depict its four, distinct zones: 1) the molecular zone, a cold and dense region where the gas is in the form of molecules and where stars could form; 2) the dissociation front, where the molecules break apart into atoms as the temperature rises; 3) the ionization front, where the gas is stripped of electrons, becoming ionized, as the temperature increases dramatically; and 4) the fully ionized flow of gas into a region of atomic, ionized hydrogen. For the first time, Webb will be able to separate and study these different zones’ physical conditions. Credits: ILLUSTRATION: NASA, ESA, CSA, Jason Champion (CNRS), Pam Jeffries (STScI), PDRs4ALL ERS Team