Molecular Clouds, Observations, Chemistry, and Ionization

References:

- Draine Ch. 32, 33

- Ryden and Pogge Ch. 7

Taxonomy and Astronomy

First, let’s try to bring some order to the various scales and densities at which molecular hydrogen can be found in our Galaxy.

In general, individual clouds are separated into categories based upon their optical appearance: diffuse, translucent, or dark, depending on the magnitudes of visual extinction \(A_V\) through the cloud.

- Diffuse molecular cloud: \(A_V < 1 \) mag

- Translucent molecular cloud: \(1 < A_V < 5 \) mag

- Dark cloud: \(5 < A_V < 20 \) mag

- Infrared Dark cloud: 20 up to \(> 100 \) mag

Diffuse and translucent clouds have sufficient UV radiation to keep gas-phase carbon photoionized throughout the cloud. These types of clouds are usually pressure-confined.

The typical dark cloud is self-gravitating, and some contain regions with \(A_V\) up to 20 mag.

There are some examples of dark clouds that are opaque to background PAHs even at 8 microns wavelengths, (indicating \(A_V > 100\) mag) these are called infrared dark clouds.

These terms describe the surface density of the cloud in terms of visual extinction. But, molecular clouds are not a one-parameter family, and there are other terms to describe cloud properties (not always uniformly employed)!

- We can distinguish a giant molecular cloud (GMC) from a dark cloud based on total mass.

- Groups of distinct clouds are called cloud complexes

- Structures within a cloud (self-gravitating) are called clumps

Clumps may or may not be forming stars. If they are, they are called star-forming clumps. Cores are density peaks within star-forming clumps that will form a single star (or a binary star).

Molecular clouds are sometimes found in isolation, but in most cases they are grouped together into complexes. Large complexes hav substructure, though, so the distinction between “cloud” and “cloud complex” is somewhat arbitrary. Observers use intensities, radial velocities, and thermal emission from dust to delineate boundaries.

Draine Table 32.3 has a nice summary of the terminology used for cloud complexes and their components.

Most molecular mass is found in large clouds known as “giant molecular clouds” or GMCs, which have masses ranging from \(10^3\,M_\odot\) to \(\sim 2 \times 10^5\,M_\odot\).

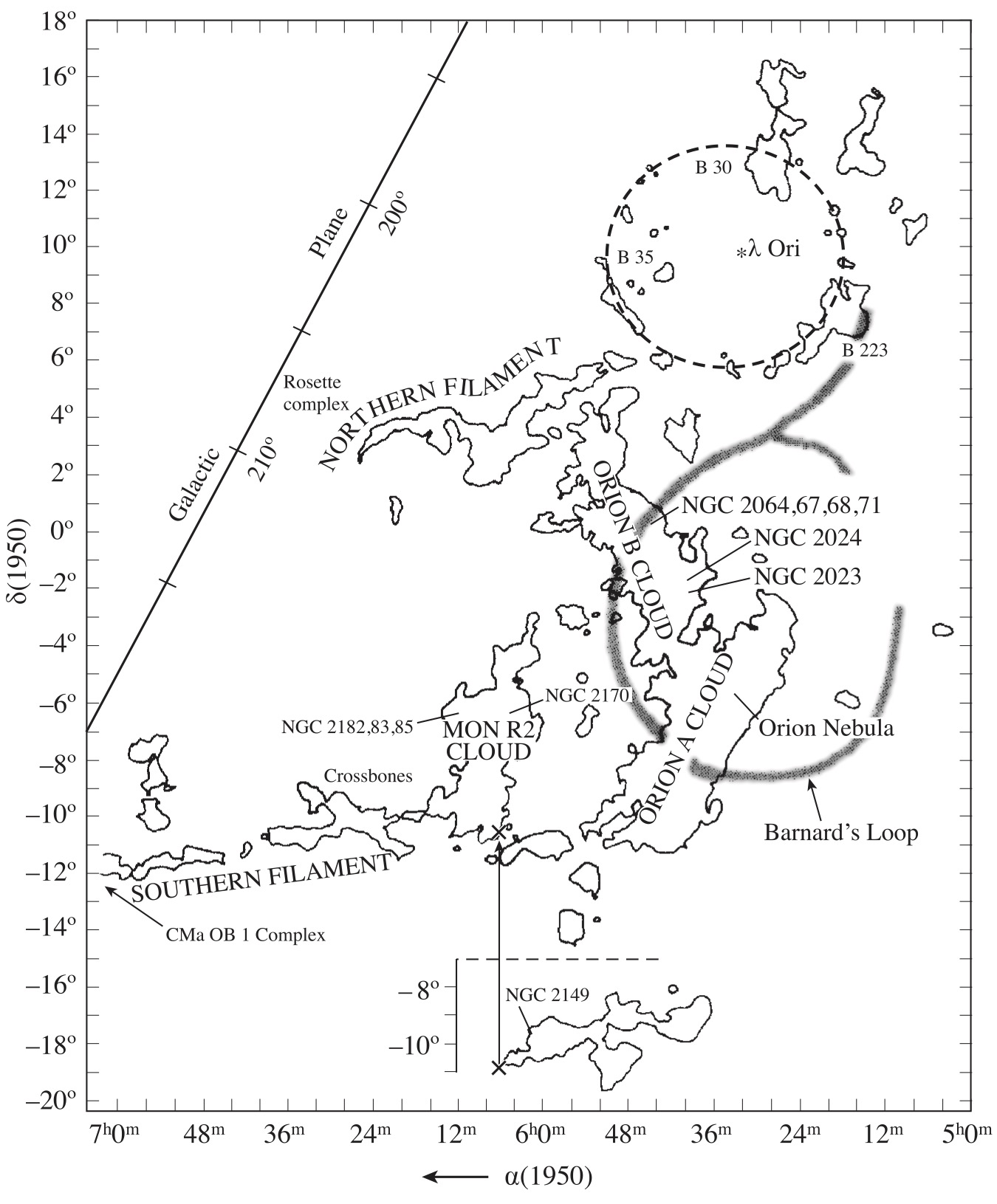

A GMC complex is a gravitationally-bound group of GMCs (as well as smaller clouds) with total mass \(> 10^{5.3}\,M_\odot\). The nearest GMC complex is the Orion Molecular Cloud (OMC) complex. Here is a map of the structure

Schematic showing the boundaries of molecular clouds in the Orion region. Three GMCs form the Orion GMC complex: Orion A, B, and the Northern Filament. Credit: Draine Figure 32.1, after Maddalena et al. 1986.

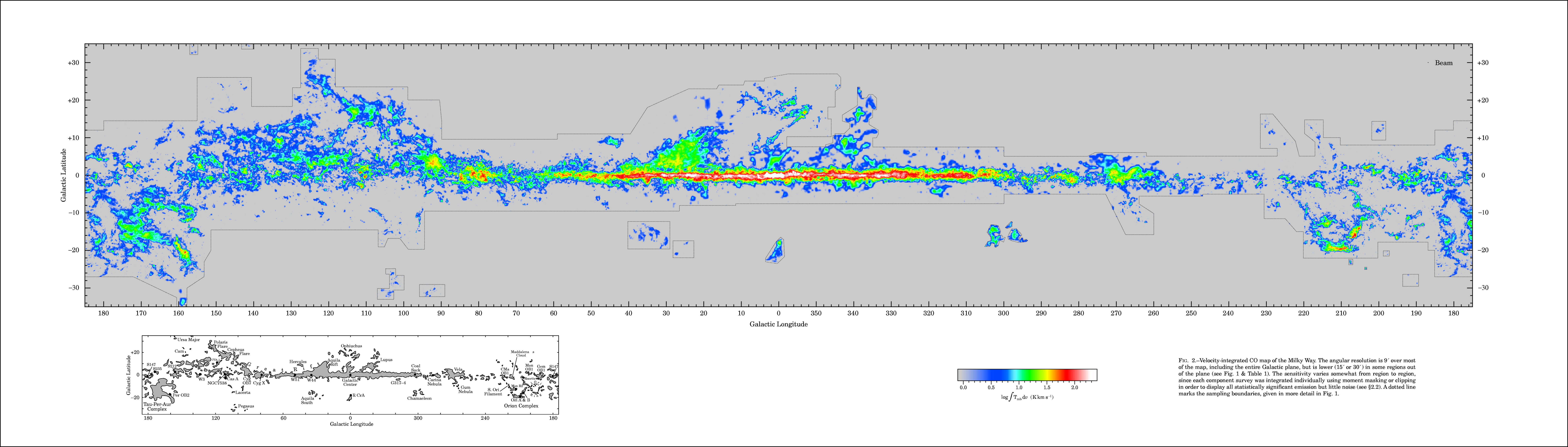

Locations of prominent molecular clouds along the Milky Way. Dame et al. 2001

Star counts

Molecular clouds were originally discovered by star counts. First, Herschel noticed in 1785 that there were patches along the Milky Way where very few stars were seen, but he incorrectly attributed this to an actual underdensity.

Now, we know that this is from the obscuration by dusty clouds.

Modern studies including J, H, K to optical surveys can now provide a very good map of dusty. In fact, coupling stellar measurements with spectral models, and in some cases distances, allows us to make a 3D map of the dust distribution in our Galaxy.

Molecular radio lines

Most common way to study molecular gas is through the \(J = 1 \rightarrow 0\) transition of carbon monoxide. The CO luminosity of a cloud is approximately proportional to the total mass of the cloud.

Additionally, using velocity information + assumed Galactic rotation curve (and conversion from CO to molecular Hydrogen) allows us to infer the surface density of molecular hydrogen over the Milky Way disk.

Gamma rays

The ISM is actually an appreciable source of gamma rays.

- cosmic rays colliding with interstellar gas (pion decay and bremsstrahlung)

- inverse Compton

- pair annihilation

Size-Linewidth Relation in Molecular Clouds

See this astrobite by Adele Plunkett.

Power-laws describing molecular clouds.

- Turbulence: velocity dispersion is proportional to cloud size

- Gravity: velocity dispersion is proportional to cloud mass

- Density: cloud size is inversely proportional to density

For larger clouds, turbulent velocities exceed local sound speed, meaning that the turbulent motions are supersonic.

The density peaks within a molecular cloud are self-gravitating. If we consider only the kinetic energy associated with fluid motions (neglect magnetic fields and pressure), we can estimate the clump mass using the virial theorem.

With modern data, laws still hold up reasonably well.

Magnetic Fields is Molecular Clouds

Virial estimate of cloud mass assumed that it was turbulence alone that was supporting the cloud. But, strong evidence from Zeeman 21-cm observations that there is significant B field in H I gas.

Energy dissipation in molecular clouds

For clouds bigger than 0.02 pc, turbulent motions are supersonic. Strongly supersonic for clouds larger than 1 pc.

Ongoing research area.

Shocked gas would quickly cool and then radiate away kinetic energy, and the clouds would collapse quickly.

So what is the source of additional energy that is injected into the turbulent motions? Outflows from protostars could be one possibility.

Another is that the time scale for shock waves to damp is longer than expected (but not backed up by simulations).

Molecular Clouds: Chemistry and Ionization

In the Milky Way, about 22% of interstellar gas is in molecular clouds, and most of the hydrogen there is in the form of \(H_2\).

Cosmic Rays guarantee that there are always some ions present in the gas, and in the outer layers of molecular clouds there may be enough UV radiation to photoionize metal species.

Let’s walk through the various types of reactions that can be important

- photoionization: $$ AB + h \nu \rightarrow AB^+ + e^- $$ Many molecules can be photoionized w/ photons with \(h \nu < 13.6\) eV (but not \(H_2\), which has an ionization potential of 15.43). Thus, molecular hydrogen will not be photoionized even in H I regions.

- photodissociation: $$ AB + h \nu \rightarrow AB^* \rightarrow A + B $$ For species like \(H_2\) and CO, photoexcitation leading to dissociation occurs via lines rather than continuum. This key fact allows these species to self-shield, or be partially shielded (like CO) if there is accidental overlap between important absorption lines with strong lines of \(H_2\).

- Neutral-neutral exchange reactions $$ AB + C \rightarrow AC + B $$ In a molecular cloud, most species are neutral, and so neutral-neutral collisions are frequent. Frequently, there will be an energy barrier that must be overcome for a reaction to proceed, i.e., the ABC complex must pass through an intermediate stat that has higher energy level than the initial AB + C, even for exothermic reactions. Interestingly, this isn’t the case for CO formation, which has a negligible energy barrier and can form at the low temperatures of molecular clouds $$ C + OH \rightarrow CO + H $$

- Ion-neutral exchange reactions $$ AB^+ + C \rightarrow AC^+ + B $$ Exothermic reactions of this type generally lack energy barriers, so the reaction can proceed even at low temperatures. And, the induced dipole interaction boosts the rate somewhat.

- Radiative association reactions (as we discussed in the context of molecular hydrogen). Basically, the excited complex needs to emit a photon before the complex flies apart on the timescale of a single vibrational period.