Fluids and Shocks

References:

- Ryden and Pogge Ch 5.1

- Draine Ch 34, 35, 36

Hot Ionized Medium occupies about half the volume of the ISM, but, because it is low-density, it is only a few percent by mass.

The HIM is hot because it has been shock-heated by supernovae explosions, which means it consists of a set of bubbles. For example, we live in the Local Bubble, which is 50 pc in radius and is thought to have been created by one or more SNe that went off 2 Myr ago.

The gas in the local bubble has \(T \sim 10^6\) K and density \(n_H \sim 0.004\;\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\).

The bubble does have cooler and denser regions within itself, of course. The Sun is near the edge of the Local Interstellar Cloud, which is 10 pc across and has properties consistent with the warm ionized medium (WIM, \(T\sim 8000\) K, \(n_H \sim 0.2\;\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\)).

In this lecture, we’re going to dig into how shock fronts (in particular, those from SNe) can heat the gas of the ISM.

Shock front

A shock front is a thin boundary between two regions of gas with very different densities, pressures, and bulk velocities. It will naturally tend to form from a sound wave travelling through gas.

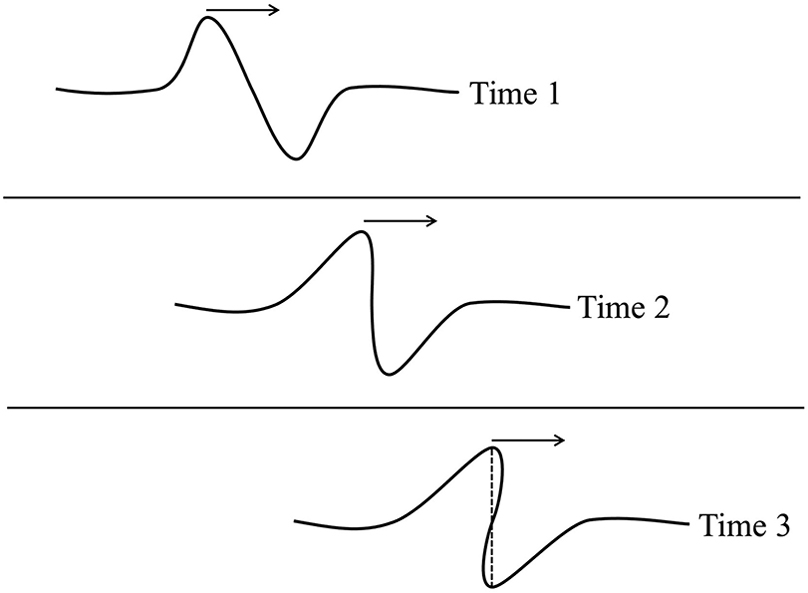

The steepening of a sound wave to form a shock. At Time 3, the sound wave is unable to be triple-valued; instead it develops a nearly discontinuous jump in pressure. Credit: Ryden and Pogge Fig 5.1.

For an adiabatic process, like the propagation of a low-amplitude sound wave, the equation of state is given by $$ P(\rho) = P_0 \left ( \frac{\rho}{\rho_0} \right)^\gamma. $$ The adiabatic index \(\gamma\) is 5/3 for a monatomic gas and 7/5 for a cool gas of diatomic molecules like \(H_2\).

The speed of propagation is $$ c_s = \left ( \frac{\gamma P}{\rho} \right)^{1/2} \propto \rho^{(\gamma - 1)/2}. $$ As long as \(\gamma > 1\), sound will travel faster in a denser gas.

Sound waves are pressure and density waves. So the crest of the wave, where the density and pressure are highest, travels faster than the trough of the wave. When the crest catches up with the trough, the gradient in density between the two steepens.

In an ocean wave, this leads to the wave breaking. But since a sound wave doesn’t have the extra dimension—at any one position there can only be one density and one pressure. So a sound wave steepens until a shock front forms.

Shock fronts on earth

Let the dimensionless amplitude of a sound wave be $$ \delta \equiv \frac{P_\mathrm{crest} - P_\mathrm{trough}}{P_\mathrm{crest} + P_\mathrm{trough}} $$ then the distance it will travel before steepening into a shock will be \(d \sim \lambda/\delta\), where \(\lambda\) is the wavelength.

Why do we not hear shock waves all the time from ordinary sounds? First, the amplitude of these fall off as the inverse square of distance, so they attenuate quickly. And, even a loud ambulance siren at the distance of 3m has a sound wave of amplitude \(\delta \sim 2 \times 10^{-4}\). But that signal would also need to travel about 2 km before steeping into a shock front.

High amplitude pressure fluctuations with \(\delta \sim 1\), like those from stun grenades and lightning bolts, will rapidly steepen into shocks.

Shock physics

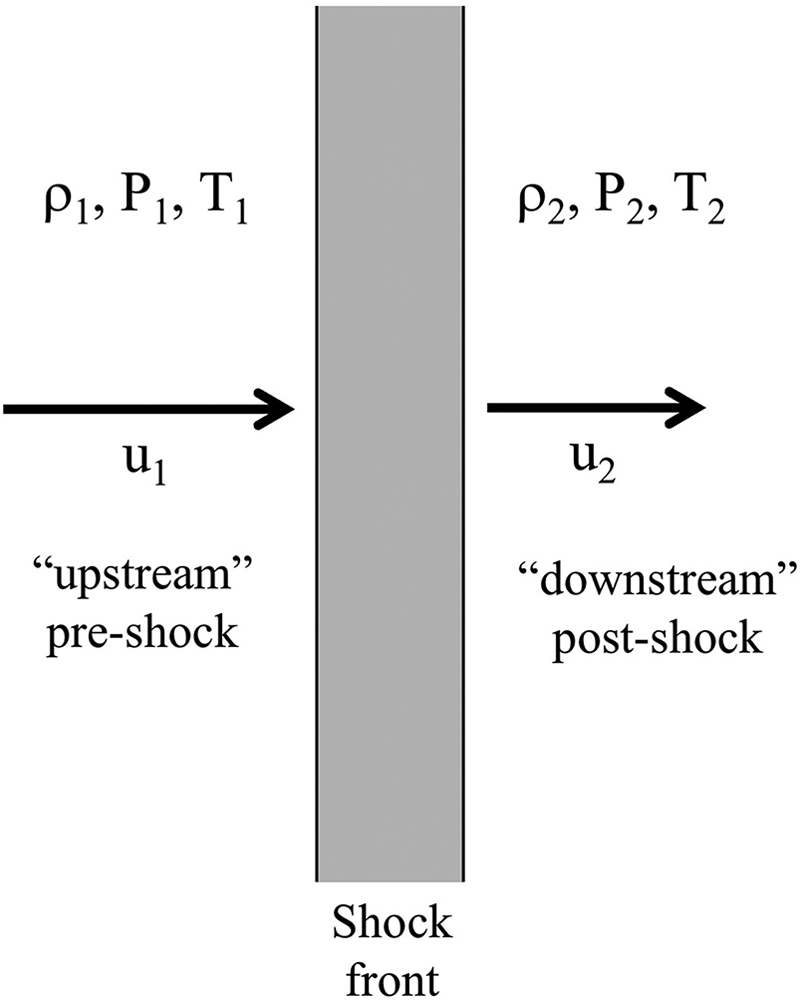

Let’s examine a plane parallel steady-state shock, where \(u\) is the speed

Geometry of a plane parallel steady-state shock.

We need to obey mass conservation $$ \frac{d}{dx} (\rho u) = 0 $$ and momentum conservation $$ \frac{d}{dx}(\rho u^2 + P) = 0 $$ and energy conservation $$ \frac{d}{dx} \left ( u \rho [u^2/2 + \epsilon] + u P\right) = 0 $$ where \(\epsilon\) is the specific internal energy of the gas, including thermal energy and rotational or vibrational energy of the molecules. In general, $$ \epsilon = \frac{1}{\gamma - 1} \frac{kT}{m} = \frac{1}{\gamma - 1}\frac{P}{\rho} $$ where \(m\) is the mass per particle. [Here we’re assuming the gas doesn’t lose energy by radiating photons, the shock is non-radiative.]

By applying these conservation laws across the shock front, we end up with the Rankine-Hugoniot conditions:

$$ \rho_1 u_1 = \rho_2 u_2 $$ and $$ \rho_1 u_1^2 + P_1 = \rho_2 u_2^2 + P_2 $$ and $$ u_1 \rho_1 [u_1^2/2 + \epsilon_1] + u_1 P_1 = u_2 \rho_2 [u_2/2 + \epsilon_2] + u_2 P_2. $$

The Mach number is a dimensionless number that is useful for describing shock fronts $$ \mathcal{M} \equiv \frac{u_1}{c_1} = \left ( \frac{\rho_1 u_1^2}{\gamma P_1} \right)^{1/2} $$ where \(c_1\) is the sound speed in the pre-shocked gas.

We can use the Rankine-Huginoit conditions to solve for the density, pressure, and temperature ratios across the shock front: $$ \frac{\rho_2}{\rho_1} = \frac{u_1}{u_2} $$ and $$ \frac{P_2}{P_1} = \frac{2 \gamma \mathcal{M}_1^2 - (\gamma - 1)}{\gamma + 1} $$ and $$ \frac{T_2}{T_1} = \frac{[(\gamma - 1) \mathcal{M}_1^2 + 2][2 \gamma \mathcal{M}_1^2 - (\gamma - 1)]}{(\gamma + 1)^2 \mathcal{M}_1^2} $$

When post-shock density, pressure, and temperature values are greater than their pre-shock values, that is equivalent to having a Mach number greater than 1. A strong shock is when \(\mathcal{M} \gg 1\). In this regime, $$ \frac{\rho_2}{\rho_1} \approx \frac{\gamma + 1}{\gamma - 1} $$ and $$ P_2 \approx \frac{2}{\gamma + 1} \rho_1 u_1^2 $$ and $$ T_2 \approx \frac{2(\gamma -1 )}{(\gamma + 1)^2} \frac{m}{k} u_1^2. $$ In the strong-shock regime, the density ratio has a finite value, which depends on the adiabatic index. For a monoatomic gas with \(\gamma = 5/3\), the post-shock gas can be at most four times the density of the pre-shock gas.

Shocks can produce very high densities and temperatures, though. An interstellar shock front with propagation speed \(u_1 \sim 1000\,\mathrm{km}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}\) produces shock-heated gas with $$ T_2 \approx 1.1 \times 10^7\,\mathrm{K} \left ( \frac{u_1}{1000\,\mathrm{km}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}} \right)^2. $$

In the frame of the shock, shock-fronts convert supersonic gas into subsonic gas. They increase the density, pressure, and temperature while decreasing the bulk velocity relative to the shock front. Shocks act to generate entropy, with the increase in specific entropy \(s_2 - s_1 \propto \ln \mathcal{M}_1\) for strong shocks.

Radiating and Cooling

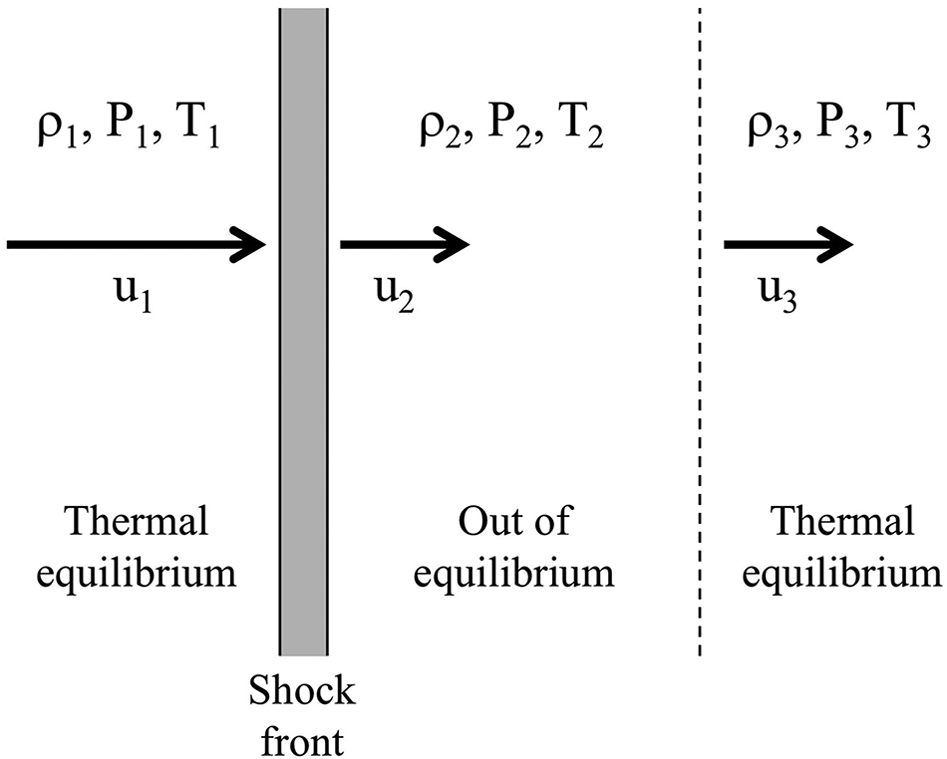

The hot shocked gas is out of equilibrium and starts cooling. So a shock is followed by a radiative zone where the shock-heated gas is cooling by emitting photons.

The structure of a plane parallel radiative shock. Credit: Ryden and Pogge Fig 5.3.

Strong, fast, hot shocks

For temperatures \(T > 2 \times 10^7\,\mathrm{K}\), the cooling is dominated by free-free (Bremsstrahlung) emission. Assuming fully ionized hydrogen gas, we get a free-free cooling time of $$ t_\mathrm{cool} \approx 24\,\mathrm{Myr}\,\left ( \frac{T}{10^7\,\mathrm{K}} \right)^{1/2} \left ( \frac{n_\mathrm{H}}{1\,\mathrm{cm}^{-3}} \right)^{-1} $$ We can recast the post-shock temperature in terms of the shock velocity, and find that in a cooling time, the gas will move a distance $$ R_\mathrm{cool} \sim u_2 t_\mathrm{cool} \sim \frac{u_1}{4} t_\mathrm{cool} \sim 6\,\mathrm{kpc} \left( \frac{u_1}{1000\,\mathrm{km}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}} \right)^2 \left ( \frac{n_\mathrm{H}}{1\,\mathrm{cm}^{-3}} \right)^{-1} $$.

This is the approximate thickness of the radiative zone for a strong shock with high temperatures. This is a long distance, especially compared to the scale height of interstellar gas in our galaxy. So, the hot gas produced by high-speed shocks doesn’t have enough time to cool before the shock runs out of gas to shock.

Slower, cooler shocks

At slightly lower temperatures, \(10^5\,\mathrm{K} < T < 2\times10^7\,\mathrm{K}\), which correspond to shock speeds of \(90\,\mathrm{km}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1} < u_1 < 1300\,\mathrm{km}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}\), collisionally-excited line emission does the cooling.

This results in a cooling time of $$ t_\mathrm{cool} \approx 0.10 \,\mathrm{Myr}\, \left(\frac{u_1}{300\,\mathrm{km}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}} \right)^{3.46} \left ( \frac{n_\mathrm{H}}{1\,\mathrm{cm}^{-3}} \right)^{-1}. $$ And we can calculate the thickness of the radiative zone as $$ R_\mathrm{cool} \sim \frac{u_1}{4} t_\mathrm{cool} \sim 8\,\mathrm{pc} \left ( \frac{u_1}{300\,\mathrm{km}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}} \right)^{4.46} \left( \frac{n_\mathrm{H}}{1\,\mathrm{cm}^{-3}} \right)^{-1} $$. These shorter time and length scales mean that radiative cooling is more effective at changing the structure of slower shocks.

Isothermal shocks

Often, it’s the case that the thermal equilibrium temperature \(T_3\) that the gas reaches after passing through the radiative zone is nearly equal to the initial temperature \(T_1\). This is called an isothermal shock, and we can re-solve the Rankine-Hugoniot conditions to find that the increase in density is $$ \frac{\rho_3}{\rho_1} = \left ( \frac{u_1}{c_1} \right)^2 = \mathcal{M}_T^2 $$ where \(\mathcal{M}_T\) is the isothermal Mach number of the shock. So, radiative shocks can reach arbitrarily high compression as their Mach number approaches infinity.