Supernovae Remnants and the Hot Ionized Medium

References:

- Ryden and Pogge Ch. 5.2

- Draine Ch. 39 and 40

Following our discussion of the physics of shock-fronts, let’s talk about how the energy deposition gets there in the first place.

Explosions are a great way to deposit a lot of energy into a tiny volume of gas over a short period of time. The first nuclear fission bombs provided an urgent need for study, and independently, Leonid Sedov and Geoffrey Taylor found analytic self-similar solutions for the expansion of a non-radiative spherical shock front.

What does self-similar mean? Basically, scale-invariance, like a power law or fractal nature.

The Sedov-Taylor solution can be applied to the explosion of fission bombs \(10^{20}\,\mathrm{ergs}\) or supernovae \(10^{51}\,\mathrm{erg}\).

There are two types of supernovae

- core-collapse: powered by gravitational collapse of the dense core of an evolved massive star

- thermonuclear: powered by runaway nuclear fusion in a degenerate white dwarf

Supernovae Remnants

Let’s consider a core-collapse for now.

- Such a core-collapse explosion produces \(\sim 10^{53}\,\mathrm{erg}\) in neutrinos. Because neutrinos have a gigantic mean-free path for interactions with low-density baryonic matter, this energy is mostly lost and not deposited in the ISM.

- The SNe also produces about \(\sim 10^{49}\,\mathrm{ergs}\) in photons, which is also mostly lost.

- The main energy that is deposited is in the form of kinetic energy of the expanding ejecta.

Let’s take \(M_\mathrm{ej} \sim 10\,M_\odot\) as typical ejecta mass, and \(u_\mathrm{ej} \sim 3000\,\mathrm{km}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}\), which implies a kinetic energy of $$ E = M_\mathrm{ej} u_\mathrm{ej}^2 \sim 10^{51}\,\mathrm{erg}. $$

[Though thermonuclear SNe have a lower ejecta mass, their ejecta speed is higher, and so they have approximately a similar kinetic energy.]

Free-expansion phase

The first stage after an SNe explosion is the free-expansion phase, where the ejecta travel ballistically outward at nearly constant speed.

The ejecta are only slowed down significantly when they have swept up a mass of ISM gas comparable to the mass of the ejecta, which occurs at $$ r_\mathrm{sweep} = \left ( \frac{3 M_\mathrm{ej}}{4 \pi \rho_1} \right)^{1/3} = 4.1\,\mathrm{pc} \left ( \frac{M_\mathrm{ej}}{10\,M_\odot} \right)^{1/3} \left ( \frac{n_\mathrm{H}}{1\,\mathrm{cm}^{-3}} \right)^{-1/3}. $$

For most conditions, we expect this to last about 1000 yrs.

The initial speed of the ejecta (3000 km/s) is much greater than the sound speed in the ISM gas (~ 1 km/s), so this creates a shockwave, like a bullet moving through the Earth’s atmosphere (Mach number » 1).

Immediately behind the shock front, the shock-heated gas has a very high pressure \(P_2\). But, the gas of the ejecta is also becoming less dense as it expands (and less hot). When the pressure within the ejecta becomes small relative to the pressure of the recently shock-heated interstellar gas, a reverse shock propagates backward toward the center of the SNe remnant, shock-heating the ejecta.

Cartoon of the free-expansion phase:

- strong, spherical shock is expanding outward into the ISM

- behind the shock, is a layer of hot, relatively dense gas, consisting of mixed ejecta and interstellar gas

- interior to that is a core of hot, low-density gas consisting of ejecta shock-heated by the reverse shock

Real SNe remnants may be more complicated, for example, the Crab Nebula seems to have speed up its expansion, possibly accelerated by the magnetized pulsar at the heart of the nebula.

Sedov-Taylor Phase

After the free-expansion phase is over, the remnant transitions into the Sedov-Taylor phase, also considered the blastwave phase. In this phase,

- the amount of shocked ISM gas is much greater than the original mass of the ejecta, so the shock front no longer depends on \(M_\mathrm{ej}\).

- The amount of energy radiated by photons is much smaller than the initial kinetic energy \(E\), though, so things still depend on the initial \(E\) deposited.

- \(P_2 \gg P_1\), so properties of the shock don’t depend on surrounding medium

- Properties of shock do depend on \(\rho_1\), the density of the surrounding medium

The two important quantities, \(E\) and \(\rho_1\), cannot be combined to form a characteristic length scale or timescale for the problem. And, it’s not relevant to introduce physical constants because

- gravity is negligible: \(G\)

- the shock is non-relativistic and non-radiative: \(c\)

- classical (not quantum): \(\hbar\)

So the conclusion is that the solution to the shock propagation is scale-free, or self-similar.

One class of self-similar solutions are power-laws, so let’s try writing the radius as a function of time like $$ r_\mathrm{sh}(t) = A E^\alpha \rho_1^\beta t^\eta $$ where \(A\) is a dimensionless pre-factor. It turns out that in order to get an expression with the correct units, the exponents are such that $$ r_\mathrm{sh} = A \left ( \frac{E t^2}{\rho_1} \right)^{1/5}. $$

And we can solve for the expansion speed of the shock front $$ u_\mathrm{sh} = \frac{2}{5} A \left ( \frac{E}{\rho_1 t^3} \right)^{1/5} = \frac{2}{5} \frac{r_\mathrm{sh}}{t} \propto r_\mathrm{sh}^{-3/2} $$

These equations can be applied to supernova remnants in the Sedov-Taylor phase and, along with a distance estimate, be used to calculate the age of the remnant.

Sedov and Taylor both found solutions for the density, velocity, and pressure as a function of time $$ \rho(r, t) = \rho_1 f(x), $$ and $$ u(r, t) = \frac{r_\mathrm{sh}(t)}{t} g(x), $$ and $$ P(r, t) = \frac{\rho_1 r_\mathrm{sh}^2(t)}{t^2} h(x), $$ where \(f, g, h\) are dimensionless functions of the dimensionless radius \(x = r/r_\mathrm{sh}(t)\). Using the conservation equations of momentum, energy, and entropy for a spherically symmetric system, you get three differential equations that you can solve for \(f, g, h\) as a function of \(x\), and there you go. It’s difficult to do in practice.

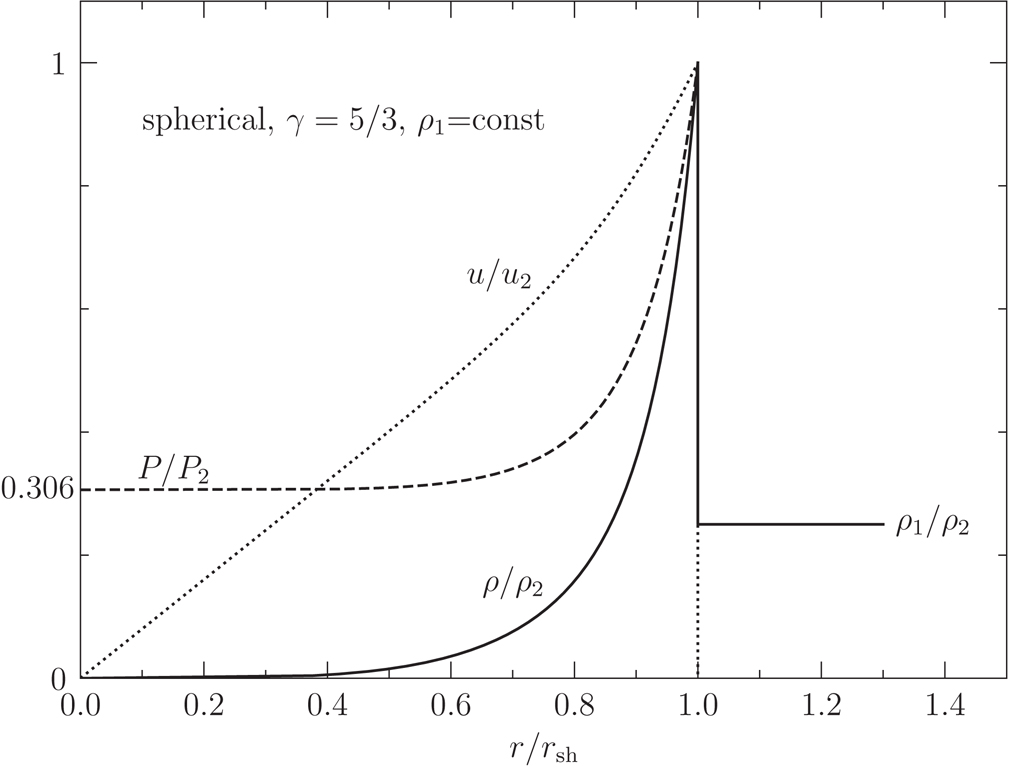

Sedov-Taylor solution for a spherical blastwave with \(\gamma = 5/3\). The density, velocity, and pressure are normalized by their immediate post-shock values \(\rho_2, u_2, P_2\). The plotted velocity \(u\) is relative to the center of the blastwave. Credit: Ryden and Pogge Fig 5.4.

Notice the steep rise in density as a function of radius.

- Q: What does this imply about the structure of a supernova remnant?

- A: most of the mass lies in a relatively thin outer layer. About 50% of the remnants mass likes within the outermost 17% of its volume.

The Sedov-Taylor phase lasts until the amount of energy radiated by the cooling gas is comparable to the initial energy \(E\). Because free-free cooling at very high temperatures is not that effective, the gas won’t cool that much until \(T_2\), the temperature in the hot dense region just behind the shock, drops below \(2 \times 10^7\) K, at which point collisionally excited line radiation will take over.

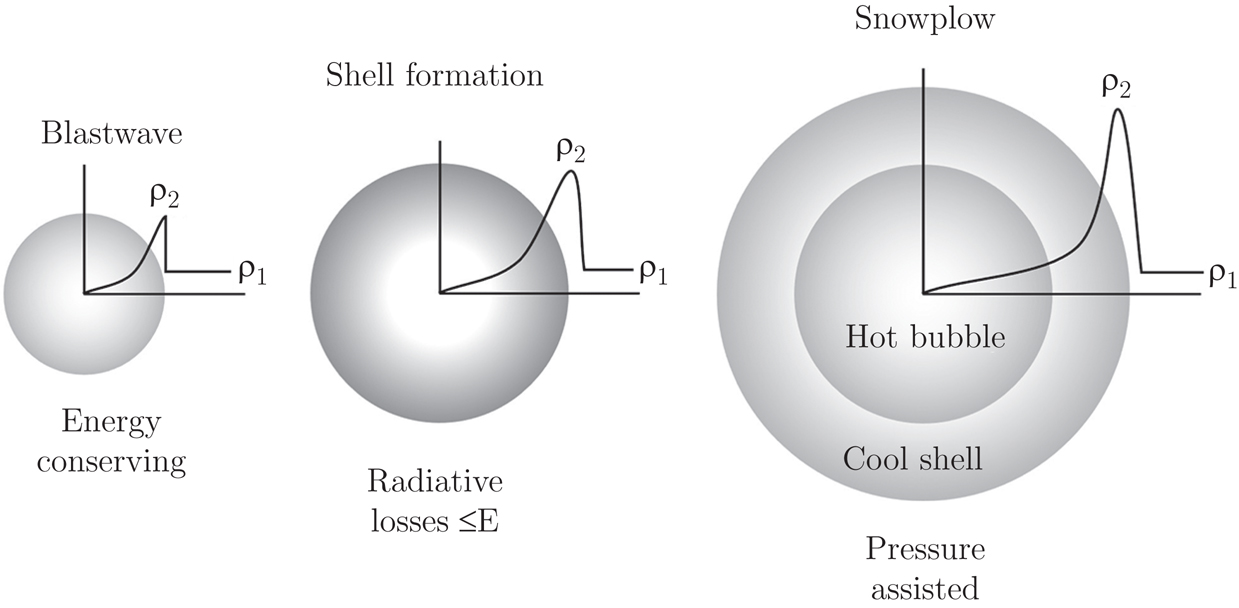

This gives us a handle on understanding supernova remnants that have ages between 1,000 yr and 40,000 yr. Once radiative losses become important at \(t \sim t_\mathrm{cool}\), a dense shell forms behind the shock (as seen in the following figure), and the supernova remnant enters the snowplow phase.

An expanding supernova remnant makes the transition from the Sedov-Taylor (blastwave) phase to the snowplow phase. Credit: Ryden and Pogge Fig 5.5, Following Shu 1992.

Snowplow phase

In the snowplow phase, the dense shell contains most of the mass of the SNe remnant, so its mass at time \(t \sim t_\mathrm{cool}\) is $$ M_\mathrm{sh} \sim \frac{4 \pi}{3} \rho_1 r_\mathrm{cool}^3 \sim 1600\,M_\odot $$

This phase is called the snowplow phase because, just as a snowplow does, it scoops up additional mass as it expands.

In this phase, most of the mass is in the dense shell. The inner region still contains gas at very high temperatures. Even though it’s low density, this gas has high pressure, which helps push the dense shell outward. So, this is called the pressure-assisted snowplow phase.

Let’s briefly analyze the forces at play. Let \(P_i\) be the mean pressure within the hot, low-density interior of the SNe remnant. This gas cannot cool effectively, so its pressure only drops through adiabatic expansion $$ P V^\gamma = \mathrm{const} $$ meaning the pressure drops as $$ P_i \propto V^{-\gamma} \propto r_\mathrm{sh}^{-3 \gamma}. $$ Positing that there exists a power-law solution, and using conservation of momentum, we can approximate the expansion of the shell in this phase as $$ r_\mathrm{sh}(t) = r_\mathrm{cool} \left ( \frac{t}{t_\mathrm{cool}} \right)^{2/7} $$ (order of magnitude 58 pc in this phase).

And expansion speed $$ u_\mathrm{sh} = \frac{2}{7} \frac{r_\mathrm{cool}}{t_\mathrm{cool}} \left ( \frac{t}{t_\mathrm{cool}} \right)^{-5/7} $$ of order 16 km/s at 1 Myr.

Eventually, the expansion speed drops to the sound speed of the surrounding medium, and the shell degenerates into an expanding sound wave, of order 35 Myr after the SNe, and shell radius 160 pc.

So, hopefully this combination of the free-expansion phase, the Sedov-Taylor phase, and the snowplow phase has provided a schematic for understanding how the hot SNe blow hot, low-density bubbles surrounded by dense shells. Which, over timescales of 35 Myr, grow to be 300 pc in diameter. These bubbles from SNe remnants are the origin of the hot ionized medium.