Star Formation: Observations

References:

- Draine Ch 42

- Stahler and Palla (2005) (comprehensive textbook)

Terminology refresher

- “Dark cloud” defined via magnitudes of optical extinction (\(A_V > 5\,\mathrm{mag}\))

- “Cores” are self-gravitating density peaks within an isolated dark cloud, which have masses from \(0.3 - 10\,M_\odot\), each is likely to form a single star or a binary star

- Within giant molecular clouds (GMCs), clump refers to self-gravitating regions with masses as large as \(10^3\,M_\odot\).

- clumps may or may not be forming stars. Those that are are called star-forming clumps. Each clump with generally contain a number of cores.

Core collapse to form stars

When the core becomes gravitationally unstable, it will begin to collapse.

The free-fall timescale is $$ \tau = \sqrt{\frac{3 \pi}{32 G \rho}} $$

- In initial stages, radiative cooling in the molecular lines keeps the gas cool. This means that gas pressure remains unimportant during this phase so the matter can move inward nearly in free-fall.

- In interior of the core, the density is higher, and so the free-fall time is shorter there. This leads the core to collapse in an “inside-out” manner, where the center collapses on itself first, and the outer material falls onto the central matter later.

As we discussed in the previous lecture, molecular clouds appear to have magnetic energies comparable to the kinetic energy (from turbulent motions) and an abundance of angular momentum that needs to be shed before collapse can complete.

The fact that stars do form implies that ambipolar diffusion (or some other process) is able to reduce the magnetic field to below some critical value such that it no longer prevents gravitational collapse.

Ambipolar diffusion: Normally, we assume that the magnetic field is “frozen” into the plasma. Indeed, the magnetic field is coupled to charged particles (electrons, ions, and charged dust grains). But, the plasma can drift relative to the neutral gas as they become uncoupled. In a molecular cloud, where the fractional ionization is very low, neutral particles will only rarely encounter charged particles, so they aren’t completely hindered in their collapse. The magnetic force on the plasma is balanced against the force resulting from collisions of charged particles with neutrals. And so we get a timescale for the magnetic field to “slip” out of the clump. For high densities \(n_\mathrm{H} \gtrsim 10^5\,\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\) the timescale is short enough \(\lesssim 3 \times 10^6\,\mathrm{yr}\) such that this mechanism may be able to reduce the magnetic flux in a contracting clump.

Infalling gas will generally have nonzero angular momentum, and as long as it remains relatively cold, it will collapse to form a rotationally supported disk. The material with the lowest specific angular momentum will be collected in a central protostar.

The dominant sources of energy are

- gravitational energy released as material is added to the protostar and it contracts

- energy released when the protostar starts to burn deuterium, and then hydrogen (main sequence)

Protostar classes

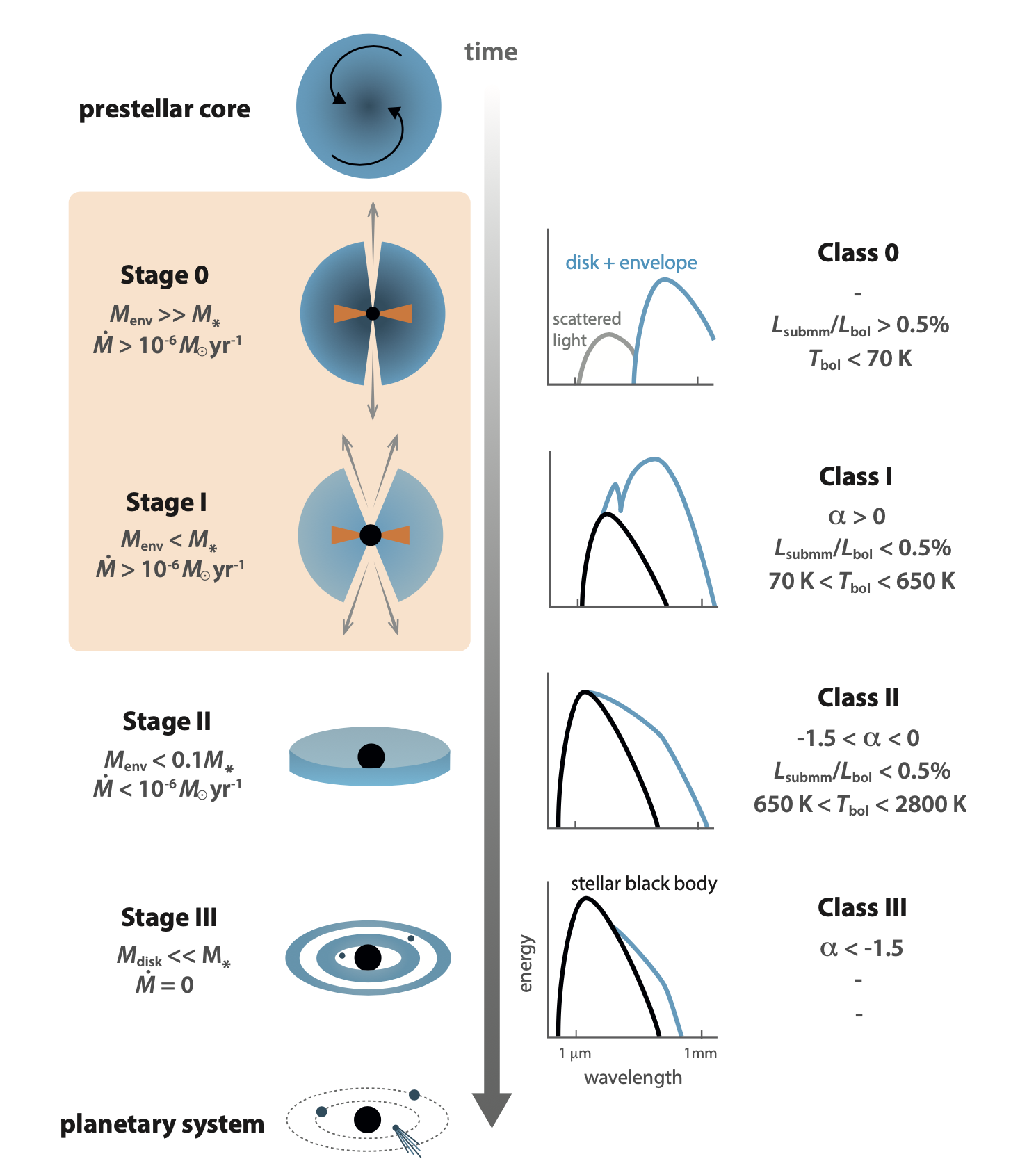

Protostellar systems (protostars and their disks) are conventionally divided into four different classes based on the overall shape of their infrared spectrum, characterized by their spectral index $$ \alpha \equiv \frac{d \log(\lambda F_\lambda)}{d \log \lambda}. $$ i.e., $$ \nu F_\nu \propto \nu^{-\alpha}. $$ Observationally, this is usually calculated using observations done at 2.2 microns (K-band) and 10 microns (N-band), which are observable from the ground.

Schematic overview of the different stages of low-mass star formation (left) and the observational classification based on the spectral energy distribution (right). The embedded phase is characterized by Stage 0 and Stage 1. Credit: Merel van’t Hoff, Ph.D. thesis.

Initial Mass Function (IMF)

If we go to a large star-forming region like the Orion Nebula Cluster, we can tabulate all of the stellar masses that we see and estimate the distribution of initial stellar masses, called the initial mass function (IMF).

Starting with Salpeter in 1955, many people have studied the IMF in different regions of the Milky Way and other galaxies. There is no immediate reason why we should expect the IMF to be universal (e.g., metallicity? turbulence? magnetic fields?), but studies seem to show remarkable uniformity from region to region. Thus far, any systematic differences appear to be very small.

Stellar initial mass function (IMF) as estimated by Kroupa (2001) and Chabrier (2003). The y-axis is \(d N / d \ln M\), the number of stars formed per logarithmic interval in stellar mass, normalized to the value at \(M = 1\,M_\odot\). Credit: Draine Figure 42.1

It’s hard to estimate the IMF at the high mass end because high-mass stars are rare (and in any SF region, you may only have a few). It’s hard to estimate the IMF at the low mass end because low-mass stars are faint. But over the range \(0.01 to 50\,M_\odot\), there appears to be reasonable agreement between studies.

The mass per logarithmic mass interval peaks around \(0.5\,M_\odot\), meaning that solar-mass stars are not the most common.

The IMF can also be used to estimate core-collapse supernova rates. If all \(M > 8\,M_\odot\) stars become Type II supernovae, then the Milky Way star formation rate of \(1.3\,M_\odot\,\mathrm{yr}^{-1}\) corresponds to a Type II supernova rate of about one every 70 yrs.

Star Formation Rates

How to estimate how many stars are being formed in our Galaxy?

- Massive stars are highly luminous and create H II regions, which can be observed at large distances.

- We can use observed number of high-mass stars and theoretical estimates of stellar lifetimes to estimate the rate at which massive stars are being formed

- Then use the IMF to estimate the total rate at which stars are being formed

Related to this question is how to calculate the rate of ionizing photons in our Galaxy.

- N II emission (related to H II abundance)

- COBE data of [N II] 205 micron line

- Free-free radio emission (WMAP)

using these combined values, the total rate of star formation in the Milky Way (averaged over the past 3 Myr, which is the lifetime of early O-type stars), is about one solar mass per year.

Schmidt-Kennicutt Law

The total mass of molecular gas in the MW is \(10^9\,M_\odot\). If we say the typical density is \(n_\mathrm{H} \approx 50\,\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\), then the free-fall time of that gas would be about \(6 \times 10^6\,\mathrm{yr}\), so the maximum rate at which stars could be made would be $$ \dot{M}\mathrm{ff} = \frac{M\mathrm{tot}}{\tau_\mathrm{ff}} \approx 200\,M_\odot\,\mathrm{yr}^{-1} $$ the actual SF rate is two orders of magnitude below this. Why?

- most of the mass in giant molecular clouds is not undergoing free-fall collapse

- even in the regions that do collapse, only a fraction of the gas ends up in stars

Big question in ISM theory is why the SF rate has the observed value that it does. This is complicated because it involves

- excitation and damping of MHD turbulence in molecular clouds

- transport of angular momentum out of contracting regions

- ambipolar diffusion to remove magnetic flux from contracting regions

- important effects of “feedback”–how outflows and radiation from protostars and stars on the surrounding gas, either stimulating or suppressing further star formation.

Star-formation is the result of gravitational collapse, so one expects the specific star formation rate (SF rate per unit of gas mass) to be larger in higher density regions.

Schmidt (1959) proposed that the star formation rate per volume varied as a power of the local density \(\rho\). The volume density is difficult to determine from afar, so Kennicut (1998) examined the relationship between global star formation in a galaxy and \(\Sigma_\mathrm{gas,disk}\), which is the gas surface density averaged over the “optical disk” of the galaxy. He found that the star formation rate per unit area varied as $$ \Sigma_\mathrm{SFR, disk} = (2.5 \pm 0.7) \times 10^{-4} \left ( \frac{\Sigma_\mathrm{gas, disk}}{M_\odot\,\mathrm{pc}^{-2}} \right)\,M_\odot\,\mathrm{kpc}^{-2}\,\mathrm{yr}^{-1} $$

This is referred to as the Schmidt-Kennicut Law, and describes the global star formation rate of a galaxy. It works remarkably well from the low gas surface densities of gas-poor spiral disks to the very high surface densities in the cores of luminous starburst galaxies.

You can create an even tighter relationship if you consider the surface density of molecular gas and average over smaller volumes (for nearby, well-resolved galaxies).