The DFT and FFT

Zoom links

References for today

- The Fourier Transform and its Applications by R. Bracewell

- Interferometry and Synthesis in Radio Astronomy by Thompson, Moran, and Swenson, particularly Appendix 2.1

- Fourier Analysis and Imaging by R. Bracewell

- Wikipedia on Nyqist-Shannon sampling theorem

Review of last time

- Convolution/multiplication theorem

- Band-limited functions

- Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem

- Aliasing

- “Band-limited” interpolation with sinc kernel

This time:

- Convolution/Interpolation with different kernels

- Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT)

Convolutional kernels

Now that we’ve developed our understanding of band-limited functions, sampling, and restoration, let’s make one more point about interpolation and convolutional kernels.

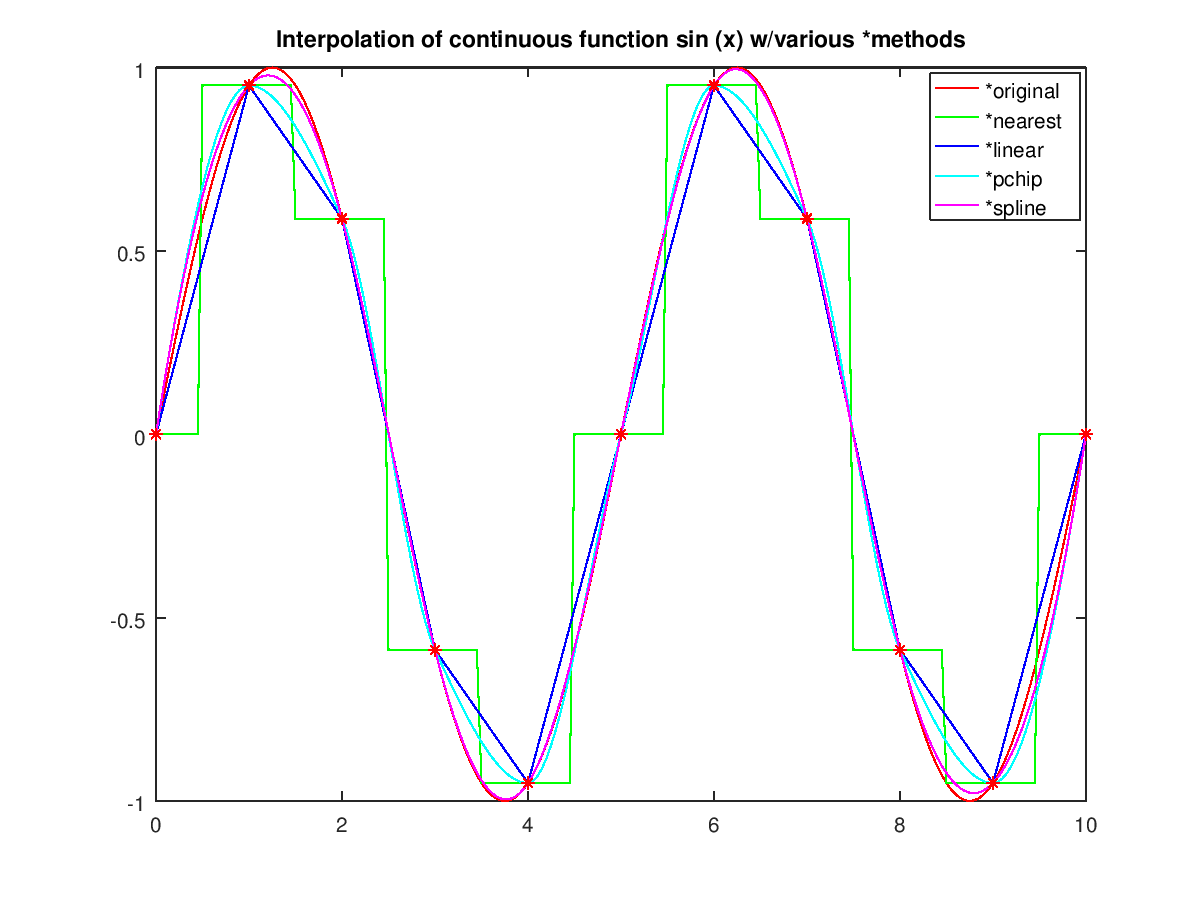

We just said that in order to restore a continuous function from a set of samples, we needed to do sinc-interpolation. What happens if we do one of the more commonly used forms of interpolation, like nearest neighbor or linear?

Credit: Octave

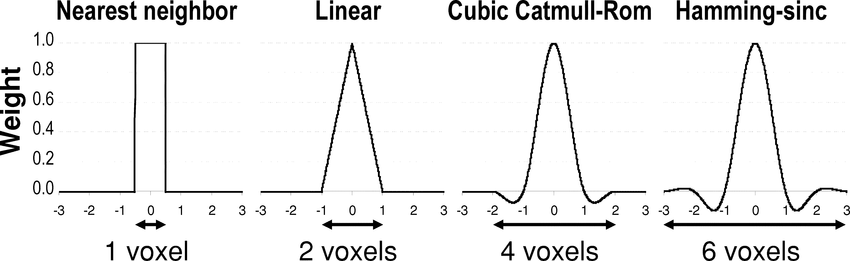

We can cast each of these as convolution with a different kind of kernel.

Credit Jeffrey Tsao.

The nearest neighbor kernel will have a corresponding Fourier transform of a sinc and the linear kernel will have a \(\mathrm{sinc}^2\). These functions all have non-zero values above the cutoff frequency. Of these, only the sinc function has zero amplitude beyond the cutoff frequency.

So reconstruction of a function using linear interpolation, for example, will introduce higher-frequency features, like these sharp transitions around each data point. Depending on what you’re doing the interpolation for, sometimes this matters, sometimes it doesn’t. Later on, when we talk about “gridding” of visibility data from radio interferometers, the type of interpolation used will have a big impact on the dynamic range of the resulting images.

Q: Why is sinc interpolation generally not used in practice? Because the kernel size is large/infinite, you’re actually using all of the data points in each and every interpolation and this can be computationally prohibitive for many applications. Compare that to linear interpolation, which only uses the two nearest points.

The Discrete Fourier transform (DFT)

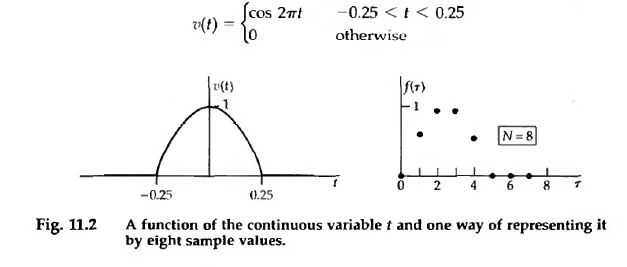

Now we’ll talk about how we deal with samples of data. We’ll stick with the same example that we’re dealing with a function of time. But rather than \(t\), having units of seconds, we’ll simply label each data point by an index \(m\) which takes on non-negative, integer values like \(m = 0, 1, \ldots, N\).

Credit: Bracewell Fig 11.2

The forward discrete Fourier transform (DFT) is $$ F_k = \sum_{m=0}^{N-1} f_m \exp \left ( - 2 \pi i \frac{m k}{N} \right) $$ and we could compute \(F_k\) for \(k = 0, 1, \ldots, N-1\).

Here, the discrete index variable \(k\) has replaced the continuous-frequency variable \(s\), just like \(m\) replaced the continuous-time variable \(t\).

The inverse discrete Fourier transform is $$ f_m = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{k=0}^{N -1} F_k \exp \left ( 2 \pi i \frac{m k}{N}\right). $$ Like the continuous-Fourier transform, one of the differences from the forward is the \(+i\) in the exponential. The other is the inclusion of the normalization pre-factor.

Note: depending on whom you talk to, you’ll see a wide variety of conventions as to where the normalization prefactor goes and where the \(2 \pi\) lives. The convention presented here is the same one used by the Python/NumPy package and the Julia/AbstractFFTs.jl package, so it should be the one you encounter most frequently.

Like the continuous Fourier transform, if you take the DFT of a set of samples and then take the iDFT of that, you will end up with the original set of samples.

Units of the DFT

The DFT only knows/assumes that it was fed a set of equally spaced samples $$ f_m = f(x_m) $$ where $$ m = 0, 1, \ldots, N - 1. $$

So, at its most abstract, the DFT takes in a bunch of \(N\) samples spaced \(\Delta x\) apart and returns \(N\) samples corresponding to the Fourier components. The frequency of each component corresponds is given by \(k/N\) in units of “cycles per sampling interval.”

I.e., so if we had \(N = 8\) samples, then the \(k=3\) frequency component returned from the DFT would be equal to \(3/8\) cycles per “the interval between samples.”

On its own, the DFT doesn’t provide any information about what type of variable \(x\) is or what the spacing is. But there is hope. We can make this concrete, we just have to be careful. Using our example of a time series with \(N=8\) samples \(\{f_m\}\), say we know that \(\Delta x = 0.1\) seconds, $$ \Delta x = x_{m+1} -x_m $$

The spacing in the frequency domain will be 1/8 cycles per 0.1 seconds, or 1.25 Hz.

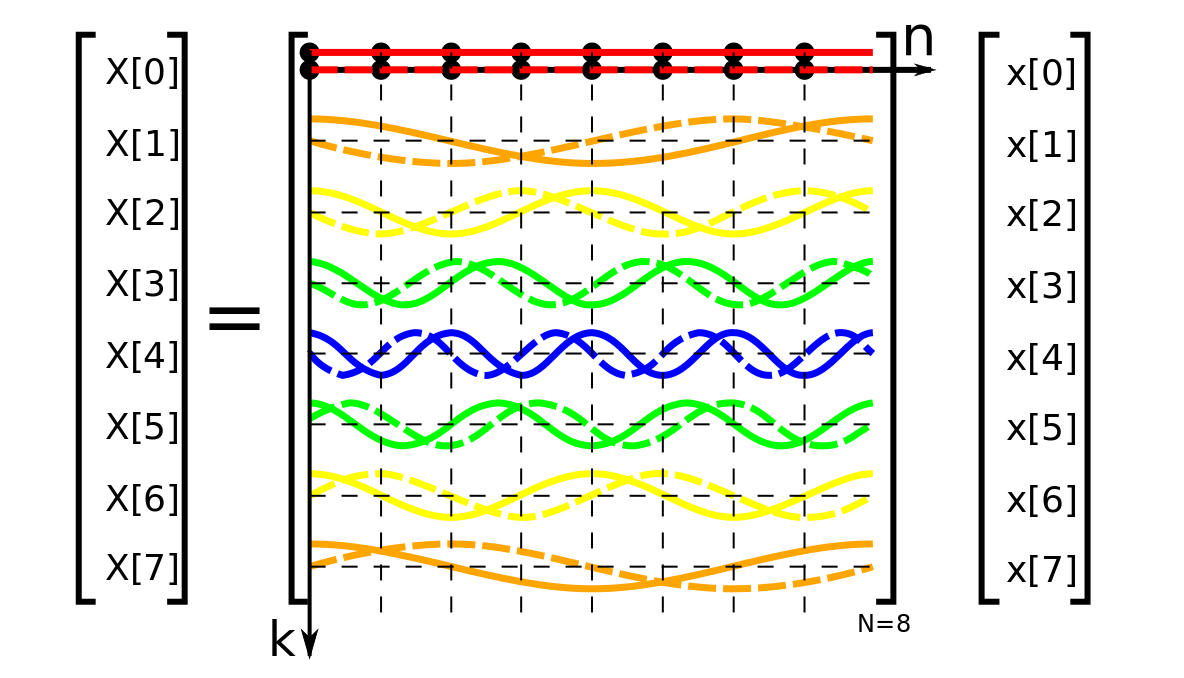

DFT as a matrix operation

Thus far we have just been talking about a “set” of samples. We can also think of the collection of data as a vector $$ \mathbf{f} = \begin{bmatrix} f_0 \\ f_1 \\ \vdots \\ f_{N-1} \\ \end{bmatrix} $$

and the frequency samples as a vector too

$$ \mathbf{F} = \begin{bmatrix} F_0 \\ F_1 \\ \vdots \\ F_{N-1} \\ \end{bmatrix}. $$

We’ve now mentioned that the Fourier transform is a linear operator a few times. Another way of demonstrating this is that we could write the DFT as a matrix multiplication $$ \mathbf{F} = \mathbf{W} \mathbf{f}. $$

If we look back at the definition of the DFT $$ F_k = \sum_{m=0}^{N-1} f_m \exp \left ( - 2 \pi i \frac{m k}{N} \right) $$ hopefully we can see how this might be cast in matrix form. If we define the quantity $$ \omega = e^{- 2 \pi i / N} $$ then we can write $$ W = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1 & \ldots & 1 \\ 1 & \omega & \omega^2 & \ldots & \omega^{N - 1} \\ 1 & \omega^2 & \omega^4 & \ldots & \omega^{2(N-1)} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 1 & \omega^{N-1} & \omega^{2(N-1)} & \ldots & \omega^{(N-1)(N-1)}\\ \end{bmatrix} $$

This formulation can be really useful if you’re into forward modeling using linear models. Because we can write the DFT as a matrix multiplication, it can essentially be just another linear transformation to your linear model. Determining the “best-fit” parameters can still be done analytically. We’ll talk about this a bit more when we get to the lecture on Bayesian inference.

The elements of the DFT matrix represented as samples of complex exponentials. Credit: Wikipedia/Glogger

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)

- Youtube/SteveBrunton on the Fast Fourier Transform

The Fast Fourier Transform or FFT is an algorithm (class of algorithms) for computing the discrete Fourier transform. Practically speaking, if you’re going to perform a Fourier transform on discrete data with a computer, you will almost certainly use an FFT algorithm, so FFT and DFT end up being synonymous.

If we have a data array of length \(N\), the complexity of the DFT is \(\mathcal{O}(N^2)\), while the complexity of the FFT is only \(\mathcal{O}(N \log N)\). This can make a huge difference in computational time if N is large. Say if you have an array of \(N = 4096\) datapoints, then you could be looking at a factor of 1000 speedup.

The development and implementation of FFT packages turned the DFT from something that was too slow for many practical applications into a formidable analysis tool. This really enabled the widespread usage of the Fourier transform in signal manipulation and data analysis. I don’t think anyone would argue with you that strongly if you said that the FFT is the most important algorithm of the last century Cornell’s top ten algorithms of the 20th century.

There are many different FFT algorithms out there. The most popular one is the Cooley-Tukey algorithm and relies on the factorization of a size \(N\) DFT matrix into \(N_1\) smaller DFTs of sizes \(N_2\) in a recursive manner. Therefore there is a (historical) preference towards array sizes that powers of \(2\). However, there are algorithms out that still give \(\mathcal{O}(N \log N)\) even for prime values of \(N\), so it’s not much of a constraint in practice.

We don’t have time to go into much more detail about the FFT algorithm here, but hopefully you can see from the structure of the \(\mathbf{W}\) matrix that there are plenty of opportunities to make the calculation more efficient by factoring and caching values.

Now, lets look at some code examples of how we might actually use the FFT in Python.